Advances in Cancer Detection

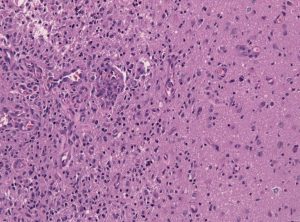

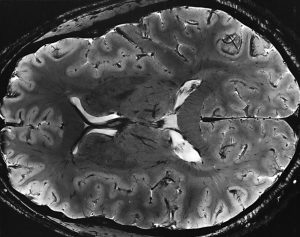

Among the deadliest and most difficult to treat types of cancer is glioblastoma, an especially aggressive form of brain cancer. Widely available imaging techniques can diagnose the tumor, but often the diagnosis is too late to treat the cancer effectively. Although blood-based cancer biomarkers can provide for earlier detection of cancer, these markers face the difficult task of crossing the blood-brain barrier (BBB), which prevents all but the tiniest molecules from moving from the brain to the bloodstream.

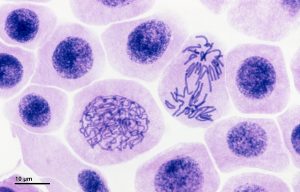

A study recently published in Scientific Reports, coauthored by Hong Chen, PhD, Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Washington University in St. Louis (WUSTL), reports of successful deployment of a strategy consisting of focused ultrasound (FUS), enhanced green fluorescent protein (eGFP), and systemically injected microbubbles to see if the BBB could be opened temporarily to allow biomarkers to pass from the brain into the bloodstream. The authors used eGFP-activated mouse models of glioblastoma, injecting the microbubbles into the mice and then exposing the mice to varying acoustic pressures of FUS. They found that circulating blood levels of eGFP were several thousand times higher in the FUS-treated mice compared to non-treated mice, which would significantly facilitate the detection of the marker in blood tests.

The method has some way to go before it can be used in humans. For one thing, the pressures used in the Scientific Reports study would damage blood vessels, so it must be determined whether lower pressures would still provide detectable transmission of proteins across the BBB. In addition, the authors must exclude the possibility of FUS unexpectedly enhancing tumor growth.

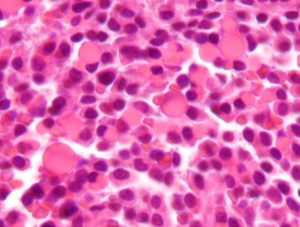

In other body areas, with easier access from tissue to the bloodstream, engineers have developed a disease-screening pill that, when ingested and activated by infrared light, can indicate tumor locations on optical tomography. The scientists, led by Greg M. Thurber, PhD, Assistant Professor of Biomedical and Chemical Engineering at the University of Michigan, reported their findings in Molecular Pharmaceutics.

The authors of the study used negatively charged sulfate groups to facilitate absorption by the digestive system of molecular imaging agents. They tested a pill consisting of a combination of these agents and found that their model tumors were visible. The next steps will include optimizing the imaging agent dosage loaded into the pill to optimize visibility. The authors believe their approach could eventually replace uncomfortable procedures like mammograms and invasive diagnostic procedures.

Liquid Assembly Line to Produce Drug Microparticles

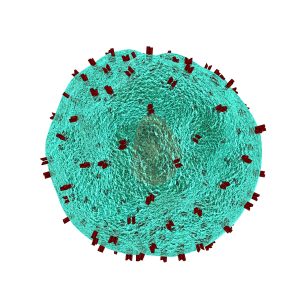

Pharmaceuticals owe their effects mostly to their chemical composition, but the packaging of these drugs into must be done precisely. Many drugs are encapsulated in solid microparticles, and engineering consistent size and drug loading in these particles is key. However, common drug manufacturing techniques, such as spray drying and ball milling, produce uneven results.

University of Pennsylvania engineers developed a microfluidic system in which more than ten thousand of these devices run in parallel, all on a silicon-and-glass chip that can fit into a shirt pocket, to produce a paradigm shift in microparticle manufacturing. The team, led by David Issadore, Assistant Professor in the Department of Bioengineering, outlined the design of their system in the journal Nature Communications.

The Penn team first tested their system by making simple oil-in-water droplets, at a rate of more than 1 trillion droplets per hour. Using materials common to current drug manufacturing processes, they manufactured polycapralactone microparticles at a rate of ‘only’ 328 billion particles per hour. Further testing backed by pharma company GlaxoSmithKline will follow.

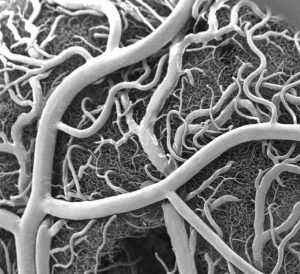

Preventing Fungal Infections of Dental Prostheses

Dental prostheses are medical devices that many people require, particularly as they age. One of the chief complications with prostheses is fungal infections, with an alarming rate of two-thirds among people wearing dentures. These infections can cause a variety of problems, spreading to other parts of the digestive system and affecting nutrition and overall well-being. Fungal infections can be controlled in part by mouthwashes, microwave treatments, and light therapies, but none of them have high efficacy.

To address this issue, Praveen Arany, DDS, PhD, Assistant Professor, Department of Oral Biology and Biomedical Engineering at SUNY Buffalo, combined 3D printing technology and polycaprolactone microspheres containing amphotericin-B, an antifungal agent. Initial fabrication of the prostheses is described in an article in Materials Today Communications, along with successful in vitro testing with fungal biofilm. If further testing proves effective, these prostheses could be used in dental patients in whom the current treatments are either ineffective or contraindicated.

People and Places

West Virginia University has announced that it will launch Master’s and doctoral programs in Biomedical Engineering. The programs will begin enrolling students in the fall. The graduate tracks augment a Bachelor’s degree program begun in 2014.

Beer is among the oldest beverages known to humankind. While we don’t know what the beer that the ancient Egyptians drank tasted like, there’s little question that the trend toward craft brewing over the past generation has resulted in a proliferation of brews with a range of colors and flavors. Beers with a strong flavor of hops are currently popular, resulting in high demand for the plant that bears them. Like many plants, however, the hop plant requires significant water and energy to produce, adding to the burden of global climate change.

Beer is among the oldest beverages known to humankind. While we don’t know what the beer that the ancient Egyptians drank tasted like, there’s little question that the trend toward craft brewing over the past generation has resulted in a proliferation of brews with a range of colors and flavors. Beers with a strong flavor of hops are currently popular, resulting in high demand for the plant that bears them. Like many plants, however, the hop plant requires significant water and energy to produce, adding to the burden of global climate change. Robots have come a long way in the past few decades, but we’re still a long way off from one that can move like animals and humans. To date, programming movement for robots uses instructions to individual mechanical parts to mimic muscle activity. The main challenge is that the number of small, coordinated muscle movements in walking requires an enormous number of instructions to program. In addition, these instructions are often not very good at accommodating for different surfaces or changing landscapes.

Robots have come a long way in the past few decades, but we’re still a long way off from one that can move like animals and humans. To date, programming movement for robots uses instructions to individual mechanical parts to mimic muscle activity. The main challenge is that the number of small, coordinated muscle movements in walking requires an enormous number of instructions to program. In addition, these instructions are often not very good at accommodating for different surfaces or changing landscapes.