Using Stem Cells to Repair Damaged Tissue

Repairing heart tissue after a heart attack is a major focus of tissue engineering. A key challenge here is keeping grafted cardiomyocytes in place within the tissue to promote repair. As we reported a couple of weeks ago, using tissue spheroids and nanowires is one approach to overcome this challenge. Another approach involves manipulating the cell cycle — the process by which normal cells reproduce, grow, and eventually die.

Making Music

People and Places

Week in BioE (October 20, 2017)

Fetal Repair Without Surgery?

Spina bifida is a fairly common type of birth defect caused by incomplete closure of the backbone and tissue surrounding the spinal cord. Fetal surgery can repair the defect before delivery, but this invasive surgery can lead to high risk preterm delivery.

A new material may dramatically reduce the invasiveness of surgery needed to correct spina bifida. In a new article in Macromolecular Bioscience, surgeons and bioengineers from the University of Colorado report on one of these alternatives. One of the lead authors was Daewon Park, Ph.D., assistant professor of bioengineering. Dr. Park and his colleagues developed a reverse thermal gel, which is an injectable liquid that forms a gel at higher temperatures when injected into the body. Ultimately a gel like this one could be injected at or near the spine, where it would cover the defect in a spina bifida patient, harden into a gel, and ultimately repair the defect by deploying stem cells or engineered tissue.

The research team’s most recent study indicates that their gel retained its stability in amniotic fluid and was compatible with neural tube cells. They also tested the gel in two animal models, with successful results. The gel is still far from being used in actual fetal surgery cases, but the authors will continue to test the gel under conditions increasingly similar to the human amniotic sac.

Building Better Brains

UCLA scientists have developed an improved system for generating brain structures from stem cells. The team of scientists, led by Bennett G. Novitch, Ph.D., professor of neurobiology at UCLA, report their findings in Cell Reports. Importantly, the methods used by Dr. Novitch and his colleagues fine-tuned and simplified earlier efforts in this area, developing a method that did not require any specific reactors to generate the tissue. They were also able to generate tissue resembling the basal ganglia for the first time, indicating promise for using these tissues to model diseases affecting that part of the brain, including Parkinson’s disease.

Next, the authors demonstrated the usefulness of these “organoids” in modeling damage due to Zika virus. After exposing the generated organoids to Zika, the authors measured the cellular responses of the tissue, demonstrating the ability to use these tissues to model the disease. Given the recent epidemic of Zika virus in the Western Hemisphere, which focused attention on the virus’s effects on the human brain, in addition to microcephaly and other birth defects when the disease is transmitted from pregnant mothers to their children, understanding how Zika affects the developing brain is key to determining how to prevent the damage it causes and possibly repairing it. Reliable models of brain development are necessary, and the UCLA team’s findings seem to indicate that they’ve found one.

Rebuilding Brain Circuits After Injury

Seeing Inside the Body

Implants That Grow With Chilren

Say What?

Chairs for BMES ’19 to Include Burdick

Jason Burdick, Ph.D., who is a professor in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Bioengineering, has been named one of the three chairs of the 2019 annual meeting of the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES), which be held here in Philadelphia on October 16-19. Dr. Burdick will share this position with two other Philadelphians: Alisa Morss Clyne, Ph.D., an associate professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics at Drexel University; and Ruth Ochia, Ph.D., an associate professor of instruction in bioengineering at Temple University. Drs. Burdick, Clyne, and Ochia will share the responsibility for planning the meeting and chairing it once it is in session.

Jason Burdick, Ph.D., who is a professor in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Bioengineering, has been named one of the three chairs of the 2019 annual meeting of the Biomedical Engineering Society (BMES), which be held here in Philadelphia on October 16-19. Dr. Burdick will share this position with two other Philadelphians: Alisa Morss Clyne, Ph.D., an associate professor of mechanical engineering and mechanics at Drexel University; and Ruth Ochia, Ph.D., an associate professor of instruction in bioengineering at Temple University. Drs. Burdick, Clyne, and Ochia will share the responsibility for planning the meeting and chairing it once it is in session.

“I am very happy to be appointed as a program chair for the 2019 BMES meeting in Philadelphia, along with Alisa Morss Clyne of Drexel University and Ruth Ochia of Temple University,” Dr. Burdick said when asked about the honor. “The three of us felt that it was important to represent the various biomedical engineering research and education programs within the city of Philadelphia, since the meeting will be held here. There is such a wealth of biomedical engineering efforts in Philly that provides great opportunities to engage in outreach and interaction with both the community and local industry during the meeting.”

Week in BioE (October 13, 2017)

Seeing and Repairing Damaged Heart Vessels

Two common diagnostic procedures in cardiology are intravascular ultrasound and cardiac angiography. These procedures are performed to quantify the amount of plaque affecting a patient’s blood vessels. This information is vital because it helps to determine how advanced heart degree is, as well as guiding treatment planning and even the course of bypass surgery. However, the current technologies used for these procedures have significant limitations. Although conventional angiography can help to quantify the plaque burden, it does not offer any information about how much of the diameter of a vessel is blocked. Intravascular ultrasound is very good at quantifying plaque burden, but it is poor at identifying smaller features of compromised blood vessels.

One solution suggested to these issues is the combination of these imaging technologies into a single multimodal technique. Scientists led by Laura Marcu, Ph.D., professor of biomedical engineering at the University of California, Davis, invented a method combining intravascular ultrasound with multispectral fluorescence lifetime imaging (FLIM). As published in Scientific Reports, the device resembles a typical cardiac catheter but contains an optical fiber within the catheter that emits fluorescent light to characterize the plaque components before treatment.

Dr. Marcu and her colleagues tested their new device in live pigs and in human coronary arteries obtained from cadavers. The fluorescence data acquired with the device were comparable to those acquired with traditional fluorescence angiography. Moreover, the device could acquire data without having to administer a contrast agent, which can be dangerous in some patients due to allergies or weakened kidneys. The authors are currently seeking FDA approval to test their combined catheter in humans.

In addition to treating vessels before a heart attack can occur, there is new work showing how to efficiently repair heart tissue after a heart attack. A team of scientists collaborating among Clemson University, the Medical University of South Carolina, the University of South Carolina, and the University of Chicago has received a $1.5 million grant from the National Institutes of Health to examine a treatment that combines stem cells with nanowires. The principal investigator on the grant is Ying Mei, Ph.D., who is assistant professor of bioengineering at Clemson. Dr. Mei’s team mixes stem cells with nanowires so that they form spheroids that are larger than single cells and thus less likely to wash away. In addition, the investigators hope that the spheroids will mitigate the issue of the transplanted cells and the recipient’s heart beating at different rhythms. If successful, the group’s treatment paradigm could be a major step forward in stem cell therapies and cardiology.

Look, Up in the Sky!

Drones became famous when deployed on battlefields for the first time a decade ago. Since then, they’ve been adopted as a technology for a variety of purposes. For example, Amazon introduced delivery drones almost a year ago, and it has plans to expand its drone fleet enormously in coming years. It was only a matter of time before engineers began to imagine medical applications for drones.

Engineers in Australia and Iraq recently investigated whether a drone could be used to monitor cardiorespiratory signals remotely. They reported their findings in BioMedical Engineering OnLine. The authors used imaging photoplethysmography (PPG), which employs a video camera to detect visual indications on the skin of heart activity. They also applied advanced digital processing technology due to the tendency of PPG to be affected by sound and movement in the area of detection. By testing the combined technologies in 15 healthy volunteers, the authors found that their data compared well with several traditional techniques for monitoring vital signs. Among the possible applications that the authors imagine for this technology is battlefield triage performed remotely using drones. In the meantime, they will seek to fine-tune the technology’s abilities.

Concussion Distressingly Common

A research letter published in a recent issue of JAMA reports that a study conducted in Canada found that one in five adolescents sustained a concussion on at least one occasion. Of the approximately 20% of the study respondents who had experienced concussions, one quarter had suffered more than one. The letter is particularly relevant to the United States because of the similar popularity in Canada of contact and semicontact sports such as ice hockey and football. In addition, the study included more than 13,000 teenagers, lending significantly reliability to the conclusions.

Ending the Time of Cholera

Although largely eradicated in the developed world, cholera remains a major public health issue in the Global South and other parts of the developing world. The disease is a bacterial infection that causes severe gastrointestinal distress. Because the disease is transmitted via water, effective public sanitation is a core requirement of an effective prevention campaign.

One technology being deployed in this fight is a smartphone microfluidics platform that can determine the presence of the pathogen that causes cholera in a sample and report the data almost immediately to public health authorities. This technology was produced by a company called PathVis, which was spun off at Purdue University based on science produced the laboratories of Tamara Kinzer-Ursem, Ph.D., and Jacqueline Linnes, Ph.D., both of whom are assistant professors in Purdue’s Weldon School of Biomedical Engineering. There are plans to test PathVis in Haiti and to expand it to detect other diseases in the future.

The Latest on CRISPR

CRISPR/Cas9 is the biggest bioengineering story to come along in some time — certainly the biggest in genetic engineering. But the mere fact that it’s here and already being used in animals and in human cell lines doesn’t mean that the story is over. For instance, the Cas9 protein, which CRISPR deploys as part of its gene editing process, is currently developed most often using a viral vector. However, this system of delivery has certain drawbacks, not the least of which is a host immune system response when levels of the deployed viral vector reach the levels necessary for CRISPR to work.

A recent study published in Nature Biomedical Engineering reports on the successful use of gold nanoparticles to deliver Cas9. The new delivery system, called CRISPR-Gold, could obviate the need to use a viral vector as part of the CRISPR induction process. So far, the authors, led by University of California, Berkeley, bioengineers Irina Conboy, Ph.D., and Niren Murthy, Ph.D., have only used CRISPR-Gold in mice, but their successful results indicate that nonviral delivery with CRISPR is possible, so CRISPR could be used for more than previously thought.

Week in BioE (September 29, 2017)

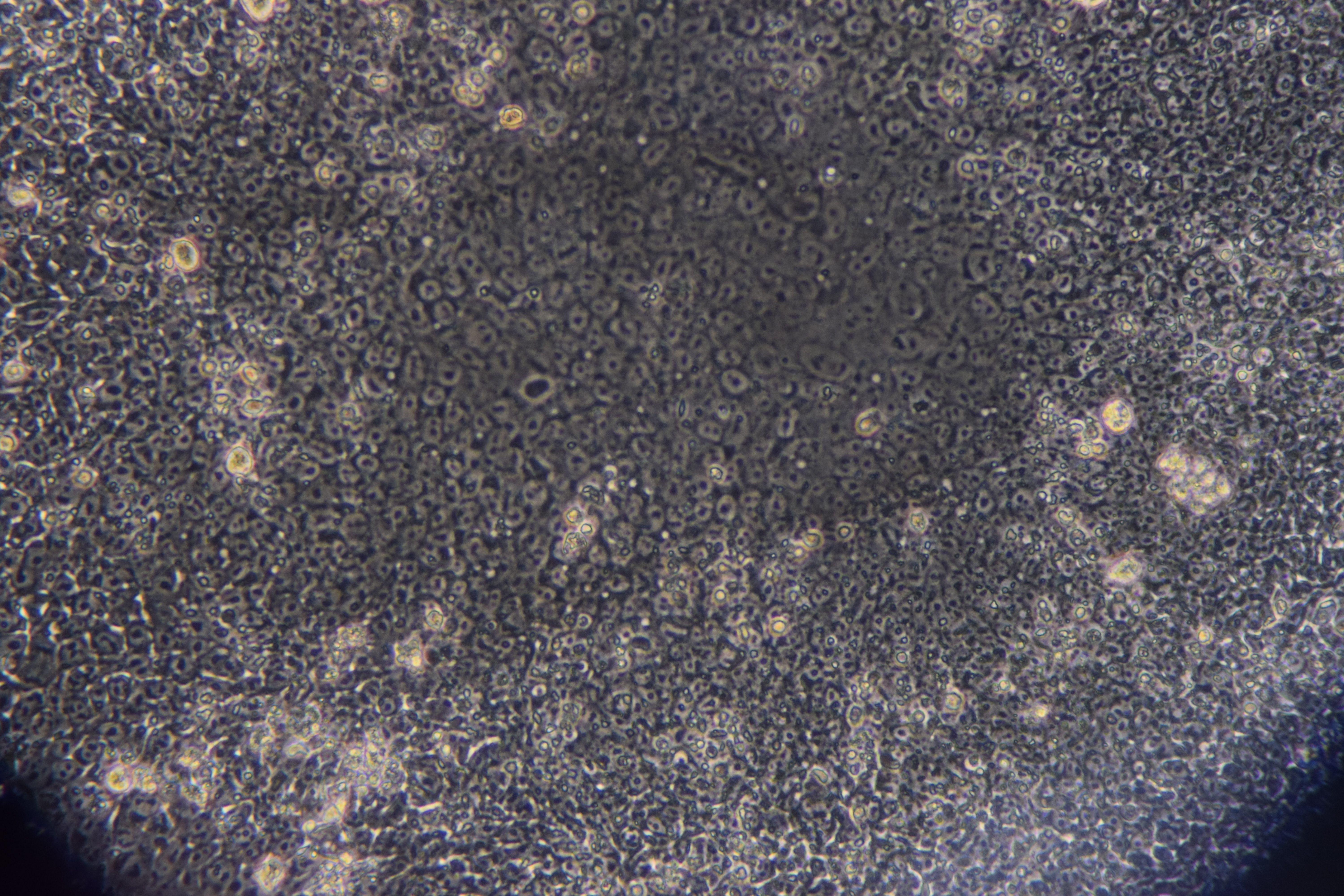

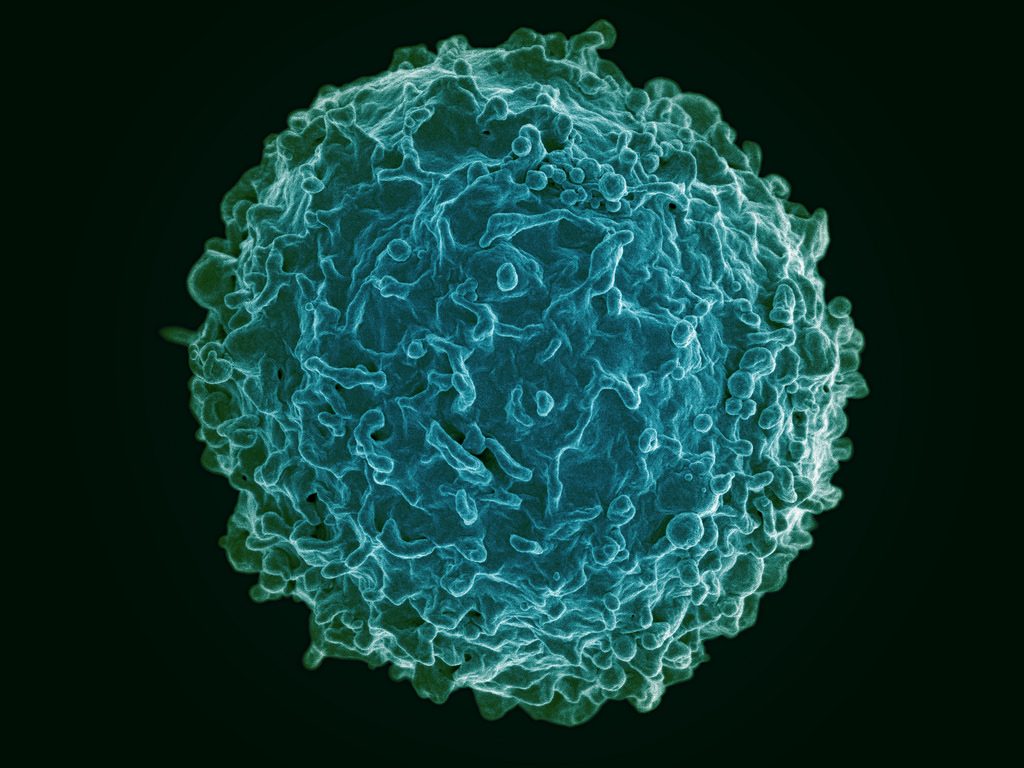

An Immune Cell Atlas

The human immune system deploys a variety of cells to counteract pathogens when they enter the body. B cells are a type of white blood cell specific to particular pathogens, and they form part of the adaptive immune system. As these cells develop, the cells with the strongest reactions to antigens are favored over others. This process is called clonal selection. Given the sheer number of pathogens out there, the number of different clonal lineages for B cells is estimated to be around 100 billion. A landscape like that can be difficult to navigate without a map.

Luckily, an atlas was recently published in Nature Biotechnology. It is the work of scientists collaborating between Penn’s own Perelman School of Medicine and faculty from the School of Biomedical Engineering, Science and Health Systems at our next-door neighbor, Drexel University. Using tissue samples from an organ donor network, the authors, led by Nina Luning Prak, MD, PhD, of Penn and Uri Heshberg, Ph.D., of Drexel, submitted the samples to a process called deep immune repertoire profiling to identify unique clones and clonal lineages. In total, they identified nearly a million lineages and mapped them to two networks: one in the gastointestinal tract and one that connects the blood, bone marrow, spleen, and lungs. This discovery suggests that the networks might be less complicated than initially thought. Also, it confirms a key role for the immune system in the gut.

Not only does this B cell atlas provide valuable information to the scientific community, but it also could serve as the basis for immune-based therapies for diseases. If we can identify these lineages and how clonal selection occurs, we could identify the most effective immunological cells and perhaps engineer them in the lab. At the very least, the extent to which scientists understand how B cells are formed and develop has received an enormous push with this research.

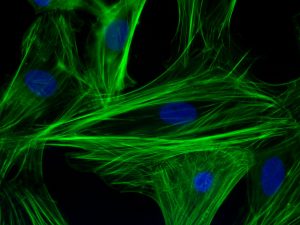

Understanding Muscle Movement

Natural movements of limbs require the coordinated activation of several muscle groups. Although the molecular composition of muscle is known, there remains a poor understanding of how these molecules coordinate their actions to confer power, strength, and endurance to muscle tissue. New fields of synthetic biology require this new knowledge to efficiently produce naturally inspired muscle substitutes.

Responding to this challenge, scientists at Carnegie Mellon University, including Philip R. LeDuc, Ph.D., William J. Brown Professor of Mechanical Engineering and Professor of Biomedical Engineering, have developed a computational system to better understand how mixtures of specific myosins affect muscle properties. Their method, published in PNAS, uses a computer model to show that mixtures of myosins will unexpectedly produce properties that are not the average of myosin molecular properties. Instead, the myosin mixtures coordinate and complement each other at the molecular level to create emergent behaviors, which lead to a robustness in how the muscle functions across a broad range. Dr. LeDuc and his colleagues then confirmed their model in lab experiments using muscle tissue from chickens. In the future, this new computational method could be used for other types of tissue, and it could prove useful in developing treatments for a variety of disorders.

Determining Brain Connectivity

How the brain forms and keeps memories is one of the greatest challenges in neuroscience. The hippocampus is a brain region considered critical for remembering sequences and events. The connections made by the hippocampus to other brain regions is considered critical for the hippocampus to integrate and remember experiences. However, this broad connectivity of the hippocampus to other brain areas raises a critical question: What connections are essential for rewiring the brain for new memories?

To offer an explanation for this question, a team of scientists in Hong Kong published a paper in PNAS in which they report on a study conducted in rats using resting-state function MRI. The study team, led by Ed X. Wu, Ph.D., of the University of Hong Kong, found that stimulation of a region deep in the hippocampus would propagate more broadly out into many areas of the cortex. The stimulation frequency affected how far this signal propagated from the hippocampus and pointed out the ability for frequency-based information signals to selectively connect the hippocampus to the rest of the brain. Altering the frequency of stimulation could affect visual function, indicating that targeted stimulation of the brain could have widespread functional effects throughout the brain.

Although human and rodent brains are obviously different, these findings from rats offer insights into how brain connectivity emerges in general. Similar studies in humans will be needed to corroborate these findings.

Seeing Inside a Tumor

Years of research have yielded the knowledge that the most effective treatments for cancer are often individualized. Knowing the genetic mutation involved in oncogenesis, for instance, can provide important information about the right drug to treat the tumor. Another important factor to know is the tumor’s chemical makeup, but far less is known about this factor due to the limitations of imaging.

However, a new study published in Nature Communications is offering some hope in this regard. In the study, scientists led by Xueding Wang, Ph.D., associate professor of biomedical engineering and radiology at the University of Michigan, used pH-sensing nanoprobes and multiwavelength photoacoustic imaging to determine tumor types in phantoms and animals. This new technology is based on the principle that cancerous cells frequently lower the pH levels in tissue, and designing probes with properties that are pH sensitive provides a method to find tumors with imaging methods and also treat these tumors.

With this technology, Dr. Wang and his colleagues were able to obtain three-dimensional images of pH levels inside of tumors. Importantly, it allowed them to noninvasively view the changes in a dye injected inside the tumor. Although a clinical application is years away, the information obtained using the Michigan team’s techniques could add significantly to our knowledge about tumorigenesis and tumor growth.

The Role of Bacteria in MS

The growing awareness of how bacteria interact with humans to affect health has led to the emergence of new scientific areas (e.g., human microbiome). Research findings from scientists collaborating between Caltech and UCSF suggest bacteria can play a role in the onset of multiple sclerosis. These investigators include Sarkis K. Mazmanian, Ph.D., Luis B. and Nelly Soux Professor of Microbiology and a faculty member in the Division of Biology and Biological Engineering at Caltech. Reporting their research results in PNAS, the researchers found several bacteria elevated in the MS microbiome. Study results showed that these bacteria regulated adaptive immune responses and helped to create a proinflammatory milieu. The identification of the bacteria interacting with immunity in MS patients could result in better diagnosis and treatment of this disabling disease.

People and Places

Week in BioE (September 15, 2017)

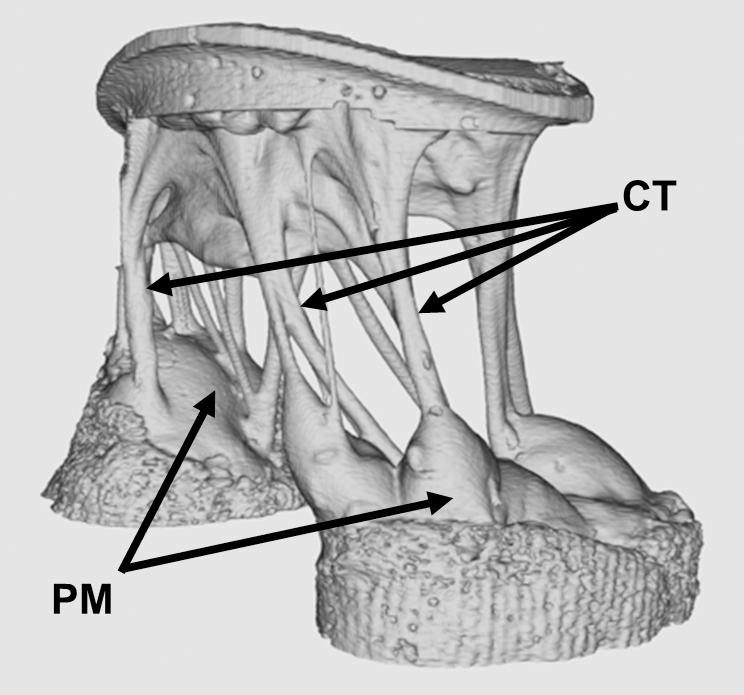

A Closer Look

Since its invention in the early 1970s, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has played an increasingly important role in the diagnosis of illness. In addition, over time, the technology of MRI has evolved enormously, with the ability to render more detailed three-dimensional images using stronger magnetic fields . However, imaging tissues under mechanical loads (e.g., beating heart, lung breathing) are still difficult to image precisely with MRI.

A new study in PLOS One, led by Morten Jensen, Ph.D., of the University of Arkansas, breaks an important technical barrier in high resolution imaging for tissues under mechanical load. Using 3D-printed mounting hardware and 7-tesla MRI, this group produced some of the highest quality images yet produced of the mitral valve exposed to physiological pressures (see above). In the longer term, this method could point to new corrective surgical procedures that would greatly improve the repair procedures for mitral valves.

Oncology Breakthroughs

Among the most significant challenges faced by surgical oncologists is developing a ‘clear margin,’ meaning that the tissue remaining after tumor excision is free of any tumor cells. If the margins are not free of tumor cells, the cancer is more likely to recur. However, until now, it has been impossible to determine if cancer cells were still present in tissue margins before finishing surgery because of the time required to test specimens.

At the University of Texas, Austin, however, scientists are getting closer to overcoming this obstacle. In a recent study published in Science Translational Medicine, this team of scientists presents the MasSpecPen — short for mass spectrometry pen. This device is capable of injecting a tiny drop of water into tissue, extracting the water after it mixes with the tissue, and quickly analyzing the sample’s molecular components. The authors, who included biomedical engineering faculty member Thomas E. Milner, Ph.D., tested the device using ex vivo samples from 253 patients with different varieties of cancer, including breast, lung, and thyroid cancers. The MasSpecPen provided sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy exceeding 96% in all cases. Although it has yet to be tested intraoperatively, if effective under those conditions, the device could become an essential part of the surgeon’s arsenal.

If the MasSpecPen could render surgical treatment of cancer more effective, a device developed at SUNY Buffalo could help doctors diagnose lung cancer earlier. Lung cancer is a particularly deadly variety of cancer because patients don’t feel any discomfort until the cancer has spread to other areas of the body. In collaboration with Buffalo’s Roswell Park Center Institute, microchip manufacturer Intel, and local startup Garwood Medical Devices, a team of scientists, including Professor Edward P. Furlani, Ph.D., from Buffalo’s Department of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering, was awarded a grant from the National Science Foundation to develop a subcutaneous implant incorporating a nanoplasmonic biochip to detect biomarkers of lung cancer. A wearable smart band would receive data from the biochip and would act as an early warning system for lung cancer. The biomarkers selected for the biochip would optimally predict lung cancer risk much earlier than the metastasis stage. If the system that the team develops is successful in diagnosing lung cancer before it spreads, it could greatly improve survival and cure rates.

Feverish Growth

Worldwide but particularly in the Global South, malaria remains a major public health concern. According to a Global Burden of Disease study in 2015, there were nearly 300 million cases of the disease in a single year, with 731,000 fatalities. One of the earliest treatments to combat malaria was invented by British colonialists, who added quinine to the tonic used in the gin and tonic cocktail. More recently the drug artemisinin was developed for fighting malaria. However, this drug and its derivatives are very expensive. The primary reason for this cost is that the drug is extracted from the sweet wormwood plant, which is in short supply. In hopes of producing a greater supply of artemisinin, scientists collaborating among Denmark, Malaysia, and the Netherlands report in Frontiers in Bioengineering and Biotechnology that transplanting the genes responsible for producing atremisinin into Physcomitrella patens, a common moss, led to a much faster production rate of the drug than what is possible with the wormwood plant. The process proved simpler and less expensive than earlier attempts to transplant genes into tobacco plants. If this potential is harnessed correctly, it could make an enormous difference in lessening the global burden of malaria.

Understanding Fear

We’ve known for years about the flight-or-fight response — the adrenergic response of our bodies to danger, which we share in common with a number of other animals. Once the decision to flee is made, however, we know far less about what determines the escape strategy used. According to Malcolm A. MacIver, professor of biomedical engineering and mechanical engineering in Northwestern University’s McCormick School of Engineering, part of the escape strategy depends on how far away the attacker is. In a paper he coauthored that was published in Current Biology, Dr. MacIver studied threat responses in larval zebrafish and found that a fast-looming stimulus produced either freezing or escape at a shorter interval following the threat perception; when the perceived threat was slow looming, longer latency following the perception of the threat was seen, resulting in a greater variety of types of escape behaviors. While it might seem a giant leap between observing behaviors in fish and higher life forms, the basic mechanism in the “oldest” parts of the brain, from an evolutionary standpoint, are less different than we might think.

People and Places

The University of Maryland has announced that construction on a new building to serve as the home of its Department of Bioengineering will be finished by the end of September. The building is to be named A. James Clark Hall, after a builder, philanthropist, and alumnus of Maryland’s School of Engineering. Further south, George Mason University in Fairfax, Va., has announced that the new chair of its Department of Engineering there will be Michael Buschmann, Ph.D., an alumnus of MIT and faculty member since the 1990s at École Polytechnique in Montreal. Congratulations, Dr. Buschmann!

Week in BioE (August 25, 2017)

Beyond Sunscreen

Excessive exposure to the sun remains a leading cause of skin cancers. The common methods of protection, including sunscreens and clothing, are the main ways in which people practice prevention. Amazingly, new research shows that what we eat could affect our cancer risk from sun exposure as well. Joseph S. Takahashi, Ph.D., who is chair of the Department of Neuroscience at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center’s Peter O’Donnell Jr. Brain Institute, was one of a team of scientists who recently published a paper in Cell Reports that found that by restricting the times when animals ate, their relative risk from exposure to ultraviolet light could change dramatically.

We tend to think of circadian rhythms as being among the reasons why we get sleepy at night, but the skin has a circadian clock as well, and this clock regulates the expression of certain genes by the epidermis, the visible outermost layer of the skin. The Cell Reports study found that food intake also affected these changes in gene expression. Restricting the eating to time windows throughout a 24h cycle, rather than providing food all the time, led to reduced levels of a skin enzyme that repairs damaged DNA — the underlying cause of sun-induced skin cancer. The study was conducted in mice, so no firm conclusions about the effects in humans can be drawn yet, but avoiding midnight snacks could be beneficial to more than your weight.

Let’s Get Small

Nanotechnology is one of the most common buzzwords nowadays in engineering, and the possible applications in health are enormous. For example, using tiny particles to interfere with the cancer signaling could give us a tool to stop cancer progression far earlier than what is possible today. One of the most recent approaches is the use of star-shaped gold particles — gold nanostars — in combination with an antibody-based therapy to treat cancer.

The study authors, led by Tuan Vo-Dinh, Ph.D., the R. Eugene and Susie E. Goodson Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Duke, combined the gold nanostars with anti-PD-L1 antibodies. The antibodies target a protein that is expressed in a variety of cancer types. Focusing a laser on the gold nanostars heats up the particles, destroying the cancer cells bound to the nanoparticles. Unlike past nanoparticle designs, the star shape concentrate the energy from the laser at their tips, thus requiring less exposure to the laser. Studies using the nanostar technology in mice showed a significant improvement in the cure rate from primary and metastatic tumors, and a resistance to cancer when it was reintroduced months later.

Nanotechnology is not the only new frontier for cancer therapies. One very interesting area is using plant viruses as a platform to attack cancers. Plant viruses stimulate a natural response to fight tumor progression, and these are viewed by some as ‘nature’s nanoparticles’. The viruses are complex structures, and offer the possibility of genetic manipulation to make them even more effective in the future. At Case Western Reserve University, scientists led by Nicole Steinmetz, Ph.D., associate professor of biomedical engineering, used a virus that normally affects potatoes to deliver cancer drugs in mice. Reporting their findings in Nano Letters, the authors used potato virus X (PVX) to form nanoparticles that they injected into the tumors of mice with melanoma, alongside a widely used chemotherapy drug, doxorubicin. Tumor progression was halted. Most importantly, the co-administration of drug and virus was more effective than packing the drug in the virus before injection. This co-administration approach is different than past studies that focus on packaging the drug into the nanoparticle first, and represents an important shift in the field.

Educating Engineers “Humanely”

Engineering curricula are nothing if not rigorous, and that level of rigor doesn’t leave much room for education in the humanities and social sciences. However, at Wake Forest University, an initiative led by founding dean of engineering Olga Pierrakos, Ph.D., will have 50 undergraduate engineering students enrolled in a new program at the college’s Downtown campus in Winston-Salem, N.C. The new curriculum plans for an equal distribution of general education/free electives relative to engineering coursework, with the expectation that the expansion of the liberal arts into and engineering degree will develop students with a broader perspective on how engineering can shape society.

People in the News

At the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign, Rashid Bashir, Ph.D., Grainger Distinguished Chair in Engineering and professor in the Department of Bioengineering, has been elevated to the position of executive associate dean and chief diversity officer at UIUC’s new Carle Illinois College of Medicine. The position began last week. Professor Michael Insana, Ph.D., replaces Dr. Bashir as department chair.

At the University of Virginia, Jeffrey W. Holmes, Ph.D., professor of biomedical engineering and medicine, will serve as the director of a new Center for Engineering in Medicine (CEM). The center is to be built using $10 million in funding over the next five years. The goal of the center is to increase the collaborations among engineers, physicians, nursing professionals, and biomedical scientists.

Week in BioE (August 10, 2017)

Preventing Transplant Rejection

Organ transplantation is a lifesaving measure for people with diseases of the heart, lungs, liver, and kidneys that can no longer be treated medically or surgically. The United Network for Organ Sharing, a major advocacy group for transplant recipients, reports that a new person is added to a transplant list somewhere in America every 10 minutes. However, rejection of the donor organ by the recipient’s immune system remains a major hurdle for making every transplant procedure successful. Unfortunately, the drugs required to prevent rejection have serious side effects.

To address this problem, a research team at Cornell combined DNA sequencing and informatics algorithms to identify rejection earlier in the process, making earlier intervention more likely. The team, led by Iwijn De Vlaminck of the Department of Biomedical Engineering, report in PLOS Computational Biology that a computer algorithm they developed to detect donor-derived cell-free DNA, a type of DNA shed by dead cells, in the blood of the recipient could predict heart and lung allograft rejection with a 99% correlation with the current gold standard. The earlier that signs of rejection are detected, the more likely it is that an intervention can be performed to save the organ and, more importantly, the patient.

Meanwhile, at Yale, scientists have used nanoparticles to fight transplant rejection. Publishing their findings in Nature Communications, the study authors, led by Jordan S. Pober, Bayer Professor of Translational Medicine at Yale, and Mark Saltzman, Goizueta Foundation Professor of Chemical and Biomedical Engineering, used small-interfering RNA (siRNA) to “hide” donated tissue from the immune system of the recipient. Although the ability of siRNA to hide tissue in this manner has been known for some time, the effect did not last long in the body. The Yale team used poly(amine-co-ester) nanoparticles to deliver the siRNA that extended and extended its duration of effect, in addition to developing methods to deliver to siRNA to the tissue before transplantation. The technology has yet to be tested in humans, but provides an exciting new approach to help solve the transplant rejection challenge in medicine.

Africa in Focus

A group of engineering students at Wright State University, led by Thomas N. Hangartner, professor emeritus of biomedical engineering, medicine and physics, traveled to Malawi, a small nation in southern Africa, to build a digital X-ray system at Ludzi Community Hospital. Once on site, Hangartner and his student team trained the staff to use system on patients. The group hopes they have made a significant contribution to improving the standard of care in the country, which currently allocates only 9% of its annual budget to healthcare. While the project admitted has limited impact, it’s important to bear in mind that expanding public health on a global level is a game of inches. The developing world will rise to the standards of the developed world one village at a time, one hospital at a time.

Speaking of Africa, the recent Ebola outbreak in West Africa had global implications and prompted many international organizations to identify better methods to identify early signs of outbreak. Since diseases like Ebola can spread rapidly and aggressively, detecting the outbreak early can save thousands of lives. To this end, Tony Hu of Arizona State University’s School of Biological and Health Systems Engineering has partnered with the U.S. Army to develop a platform using porous silicone nanodisks that, coupled with a mass spectrometer, could be used to detect Ebola more quickly and less expensively. In particular, by determining the strain of the Ebola virus detected, treatment could be more specifically individualized for the patient. Dr. Hu presents the technology in a video available here.

Neurotech News

Karen Moxon, professor of biomedical and mechanical engineering at the University of California, Davis, recently showed that rats with spinal injuries recovered to a more significant extent when treated with a combination of serotonergic drugs and physical therapy. Dr. Moxon found that the treatment resulted in cortical reorganization to bypass the injury. Many consider combining two different drugs to treat a disease or injury; Moxon’s clever approach used a drug in combination with the activation of cortical circuits (electroceuticals), and approach that was not considered possible with some types of spinal cord injuries.

At Stanford, Karl Deisseroth, professor of bioengineering and of psychiatry and behavioral sciences, led a study team that recently reported in Science Translational Medicine that mice bred to have a type of autism could receive a genetic therapy that caused their brain cells to activate differently. Although the brains of the autistic mice were technically normal, the mice were unsocial and lacked curiosity. Treatment modulated expression of the CNTNAP2 gene, resulting in increased sociability and curiosity. Their findings could have tremendous implications for treating autism in humans.

Elsewhere in neurotech, Cornell announced its intention to create a neurotech research hub, using a $9 million grant from the National Science Foundation. Specializing in types of neurological imaging, the new NeuroNex Hub and Laboratory for Innovative Neurotechnology will augment the neurotech program founded at Cornell in 2015.

Academic Developments

Two important B(M)E department have developed new programs. In Montreal, McGill University has introduced a graduate certificate program in translational biomedical engineering (video here). Also at the annual meeting of the American Society for Engineering Education in Columbus, Ohio, an interdisciplinary group of scholars from Worcester Polytechnic Institute, including three professors of engineering, presented a paper entitled “The Theatre of Humanitarian Engineering.” The authors developed an experimental role-playing course in which the students developed a waste management solution for a city. According to the paper’s abstract, a core misunderstanding about engineering is the belief that it exists separately from social and political contexts. With the approach they detail, the authors believe they could address the largely unmet call for greater integration of engineering with the humanities and social sciences on the academic level.

Week in BioE (August 3, 2017)

There’s news in bioengineering every week, to be sure, but the big story this past week is one that’s sure to continue appearing in headlines for days, weeks, and months — if not years — to come. This story is CRISPR-Cas9, or CRISPR for short, the gene-editing technology that many geneticists are viewing as the wave of the future in terms of the diagnosis and treatment of genetic disorders.

Standing for clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, CRISPR offers the ability to cut a cell’s genome at a predetermined location and remove and replace genes at this location. As a result, if the location is one at which the genes code for a particular disease, these genes can be edited out and replaced with healthy ones. Obviously, the impl ications for this technology are enormous.

ications for this technology are enormous.

This week, it was reported that, for the first time, CRISPR was successfully used by scientists to edit the genomes of human embryos. As detailed in a paper published in Nature, these scientists edited the genomes of 50 single-cell embryos, which were subsequently allowed to undergo division until the three-day mark, at which point the multiple cells in the embryos were assessed to see whether the edits had been replicated in the new cells. In 72% of them, they had been.

In this particular case, the gene edited out was one for a type of congenital heart defect, and the embryos were created from the eggs of healthy women and the sperm of men carrying the gene for the defect. However, the experiments prove that the technology could now be applied in other disorders.

Needless to say, the coverage of this science story has been enormous, so here is a collection of links to coverage on the topic. Enjoy!

- First Human Embryos Edited in U.S. (MIT Technology Review)

- Yes, U.S. Scientists Edited an Embryo’s Genes, but Super-Babies Are a Ways Away (at Slate)

- The Best Science Is Often Accidental (Baltimore Sun)

- US Scientists Are Fixing Genetic Defects in Embryos. Should You Be Nervous? (PBS Newshour)

Week in BioE (July 27, 2017)

The Brain in Focus

At Caltech, scientists are exploiting the information generated by body movements, determining how the brain codes these movements in the anterior intraparietal cortex — a part of the brain beneath the top of the skull. In a paper published in Neuron, Richard A. Andersen, James G. Boswell Professor of Neuroscience at Caltech, and his team tested how this region coded body side, body part, and cognitive strategy, i.e., intention to move vs. actual movement. They were able determine specific neuron groups activated by different movements. With this knowledge, more effective prosthetics for people experiencing limb paralysis or other kinds of neurodegenerative conditions could benefit enormously.

At Caltech, scientists are exploiting the information generated by body movements, determining how the brain codes these movements in the anterior intraparietal cortex — a part of the brain beneath the top of the skull. In a paper published in Neuron, Richard A. Andersen, James G. Boswell Professor of Neuroscience at Caltech, and his team tested how this region coded body side, body part, and cognitive strategy, i.e., intention to move vs. actual movement. They were able determine specific neuron groups activated by different movements. With this knowledge, more effective prosthetics for people experiencing limb paralysis or other kinds of neurodegenerative conditions could benefit enormously.

Elsewhere in brain science, findings of chronic traumatic encephalopathy in football players have raised significant controversy. Seeking to better understand head impact exposure in young football players, scientists from Wake Forest University led by biomedical engineer Joel D. Stitzel, fitted athletes with telemetric devices and collected four years of data and more than 40,000 impacts. They report in the Journal of Neurotrauma that, while all players experienced more high magnitude impacts during games compared to practices, younger football players experienced a greater number of such impacts during practices than the other groups, and older players experienced a greater number during actual games. The authors believe their data could contribute to better decision-making in the prevention of football-related head injuries.

Up in Canada, a pair of McGill University researchers in the Department of Neurology and Neurosurgery — Professor Christopher Pack and Dave Liu, a grad student in Dr. Pack’s lab — found that neuroplasticity might apply to more parts of the brain than previously thought. They report in Neuron that the middle temporal area of the brain, which contributes to motion discrimination and can be inactivated by certain drugs, could become relatively impervious to such inactivation if pretrained. Their findings could have impacts on both prevention of and cures for certain types of brain injury.

The Virtues of Shellfish

If you’ve ever had a diagnostic test performed at the doctor’s office, you’ve had your specimen submitted to bioassay, a test in which living cells or tissue is used to test the sampled material. University of Washington bioengineer Xiaohu Gao and his colleagues used polydopamine, an enzyme occurring in shellfish, to increase the sensitivity of bioassays by orders of magnitude. As reported in Nature Biomedical Engineering, they tested the technology, called enzyme-accelerated signal enhancement (EASE), in HIV detection, finding that it was able to help bioassays identify the virus in tiny amounts. This advance could lead to earlier diagnosis of HIV, as well as other conditions.

Mussels are also contributing to the development of new bioadhesives. Julie Liu, associate professor of chemical engineering at Purdue, modeled an elastin-like polypeptide after a substance produced naturally by mussels, reporting her findings in Biomaterials. With slight materials, Dr. Liu and her colleagues produced a biomaterial with moderate adhesive strength that demonstrated the greatest strength yet among these materials when tested under water. The authors hope to develop a “smart” underwater adhesive for medical and other applications.

Science in Motion

Discussions of alternative forms of energy have focused on the big picture, such as alleviating our dependence on fossil fuels with renewable forms of energy, like the sun and wind. On a much smaller level, however, engineers are finding smaller energy sources — specifically people.

Reporting in ACS Energy Letters, a research team led by Vanderbilt’s Cary Pint, assistant professor in the Department of Mechanical Engineering and head of Vanderbilt’s Nanomaterials and Energy Devices Laboratory Nanomaterials and Energy Devices Laboratory, designed a battery in the form of an ultrathin black phosphorous device that can generate electricity as it is bent. Dr. Pint describes the device in a video here. Although it can’t yet power an iPhone, the possibility isn’t far away.

Moving Up

Two BE/BME departments have named new chairs. At the University of Utah, David Grainger, who previously chaired the Department of Pharmaceutics and Pharmaceutical Chemistry, will become chair of the Department of Bioengineering. Closer to home, Michael I. Miller became the new chair of the Department of Biomedical Engineering on July 1. Congratulations to them both!