The COVID-19 vaccine swiftly undercut the worst of the pandemic for hundreds of millions around the world. Available sooner than almost anyone expected, these vaccines were a triumph of resourcefulness and skill.

Messenger RNA vaccines, like the ones manufactured by Moderna or Pfizer/BioNTech, owed their speed and success to decades of research reinforcing the safety and effectiveness of their unique immune-instructive technology.

Now, researchers from the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science and the Perelman School of Medicine are refining the COVID-19 vaccine, creating an innovative delivery system for even more robust protection against the virus.

In addition to outlining a more flexible and effective COVID-19 vaccine, this work has potential to increase the scope of mRNA vaccines writ large, contributing to prevention and treatment for a range of different illnesses.

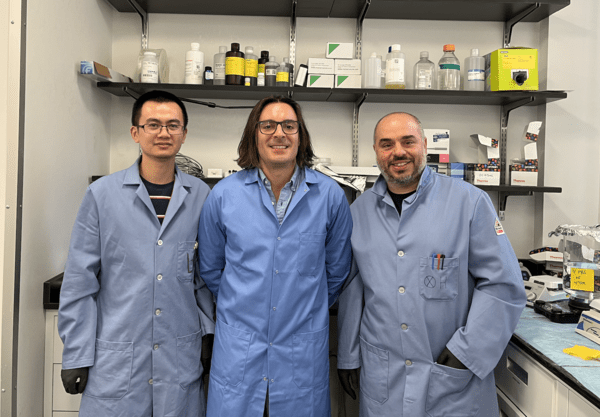

Michael Mitchell, associate professor in Penn Engineering’s Department of Bioengineering, Xuexiang Han, postdoctoral fellow in Mitchell’s lab, and Mohamad-Gabriel Alameh, postdoctoral fellow in Drew Weissman’s lab at Penn Medicine and incoming assistant professor in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at the Perelman School of Medicine, recently published their findings in Nature Nanotechnology.

mRNA, or messenger ribonucleic acid, is the body’s natural go-between. mRNA contains the instructions our cells need to produce proteins that play important roles in our bodies’ health, including mounting immune responses.

The COVID-19 vaccines follow suit, sending a single strand of RNA to teach our cells how to recognize and fight the virus.

Read the full story in Penn Engineering Today.