Penn Bioengineering is proud to congratulate Alexander Buffone, Ph.D. on his appointment as Assistant Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering at New Jersey Institute of Technology. His appointment began in the Spring of 2022.

Buffone got his Ph.D. in Chemical Engineering from SUNY Buffalo in Buffalo, NY in 2012, working with advisor Sriram Neelamegham, Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering. Buffone completed previous postdoctoral studies at Roswell Park Comprehensive Cancer Center with Joseph T.Y. Lau, Distinguished Professor of Oncology in the department of Cellular and Molecular Biology. Upon coming to Penn in 2015, Buffone has worked in the Hammer Lab under advisor Daniel A. Hammer, Alfred G. and Meta A. Ennis Professor in Bioengineering and in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, first as a postdoc and later a research associate. Buffone also spent a year as a Visiting Scholar in the Center for Bioengineering and Tissue Regeneration, directed by Valerie M. Weaver, Professor at the University of California, San Francisco in 2019.

While at Penn, Buffone was a co-investigator on an R21 grant through the National Institutes of Health (NIH) which supported his time as a research associate. Buffone is excited to start his own laboratory where he plans to train a diverse set of trainees.

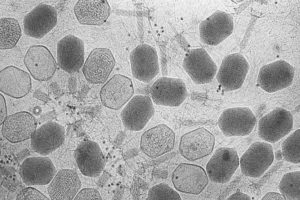

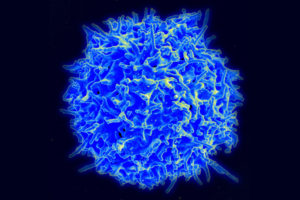

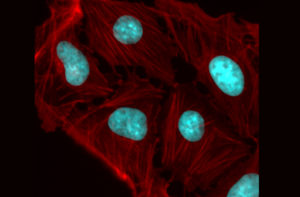

Buffone’s research area lies at the intersection of genetic engineering, immunology, and glycobiology and addresses how to specifically tailor the trafficking and response of immune cells to inflammation and various diseases. The work seeks to identify and subsequently modify critical cell surface and intracellular signaling molecules governing the recruitment of various blood cell types to distal sites. The ultimate goal of his research is to tailor and personalize the innate and adaptive immune response to specific diseases on demand.

“None of this would have been possible without the unwavering support of all of my mentors, past and present, and most especially Dan Hammer,” Buffone says. “His support in helping me transition into an independent scientist and his understanding of my outside responsibilities as a dad with two young children is truly the reason why I am standing here today. It’s a testament to Dan as both a person and a mentor.”