by Melissa Pappas

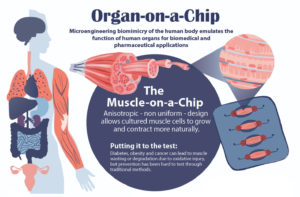

Studying drug effects on human muscles just got easier thanks to a new “muscle-on-a-chip,” developed by a team of researchers from Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science and Inha University in Incheon, Korea.

Muscle tissue is essential to almost all of the body’s organs, however, diseases such as cancer and diabetes can cause muscle tissue degradation or “wasting,” severely decreasing organ function and quality of life. Traditional drug testing for treatment and prevention of muscle wasting is limited through animal studies, which do not capture the complexity of the human physiology, and human clinical trials, which are too time consuming to help current patients.

An “organ-on-a-chip” approach can solve these problems. By growing real human cells within microfabricated devices, an organ-on-a-chip provides a way for scientists to study replicas of human organs outside of the body.

Using their new muscle-on-a-chip, the researchers can safely run muscle injury experiments on human tissue, test targeted cancer drugs and supplements, and determine the best preventative treatment for muscle wasting.

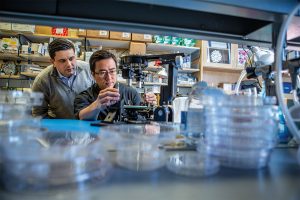

This research was published in Science Advances and was led by Dan Huh, Associate Professor in the Department of Bioengineering, and Mark Mondrinos, then a postdoctoral researcher in Huh’s lab and currently an Assistant Professor of Biomedical Engineering at Tulane University. Their co-authors included Cassidy Blundell and Jeongyun Seo, former Ph.D. students in the Huh lab, Alex Yi and Matthew Osborn, then research technicians in the Huh lab, and Vivek Shenoy, Eduardo D. Glandt President’s Distinguished Professor in the Department of Materials Science and Engineering. Lab members Farid Alisafaei and Hossein Ahmadzadeh also contributed to the research. The team collaborated with Insu Lee and professors Sun Min Kim and Tae-Joon Jeon of Inha University.

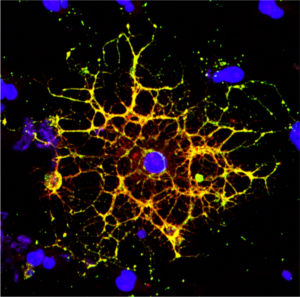

In order to conduct meaningful drug testing with their devices, the research team needed to ensure that cultured structures within the muscle-on-a-chip were as close to the real human tissue as possible. Critically, they needed to capture muscle’s “anisotropic,” or directionally aligned, shape.

“In the human body, muscle cells adhere to specific anchor points due to their location next to ligament tissue, bones or other muscle tissue,” Huh says. “What’s interesting is that this physical constraint at the boundary of the tissue is what sculpts the shape of muscle. During embryonic development, muscle cells pull at these anchors and stretch in the spaces in between, similar to a tent being held up by its poles and anchored down by the stakes. As a result, the muscle tissue extends linearly and aligns between the anchoring points, acquiring its characteristic shape.”

The team mimicked this design using a microfabricated chip that enabled similar anchoring of human muscle cells, sculpting three-dimensional tissue constructs that resembled real human skeletal muscle.

The the full story in Penn Engineering Today.

NextUp, a regular feature of Philadelphia Magazine that “highlights the local leaders, organizations and research shaping the Greater Philadelphia region’s life sciences ecosystem,” ran a profile of Philly-based agricultural startup Strella Biotechnology. Founded by Penn alumna Katherine Sizov (Bio 2019) and winner of a 2019 President’s Innovation Prize, Strella Biotech seeks to reduce food waste through innovative biosensors, and was initially developed in the

NextUp, a regular feature of Philadelphia Magazine that “highlights the local leaders, organizations and research shaping the Greater Philadelphia region’s life sciences ecosystem,” ran a profile of Philly-based agricultural startup Strella Biotechnology. Founded by Penn alumna Katherine Sizov (Bio 2019) and winner of a 2019 President’s Innovation Prize, Strella Biotech seeks to reduce food waste through innovative biosensors, and was initially developed in the