By Xuanjie (Lucas) Gong, Biotechnology MS ’19; Shihan Dong, Biotechnology MS ’19; and Princess Aghayere, Health & Societies ‘19

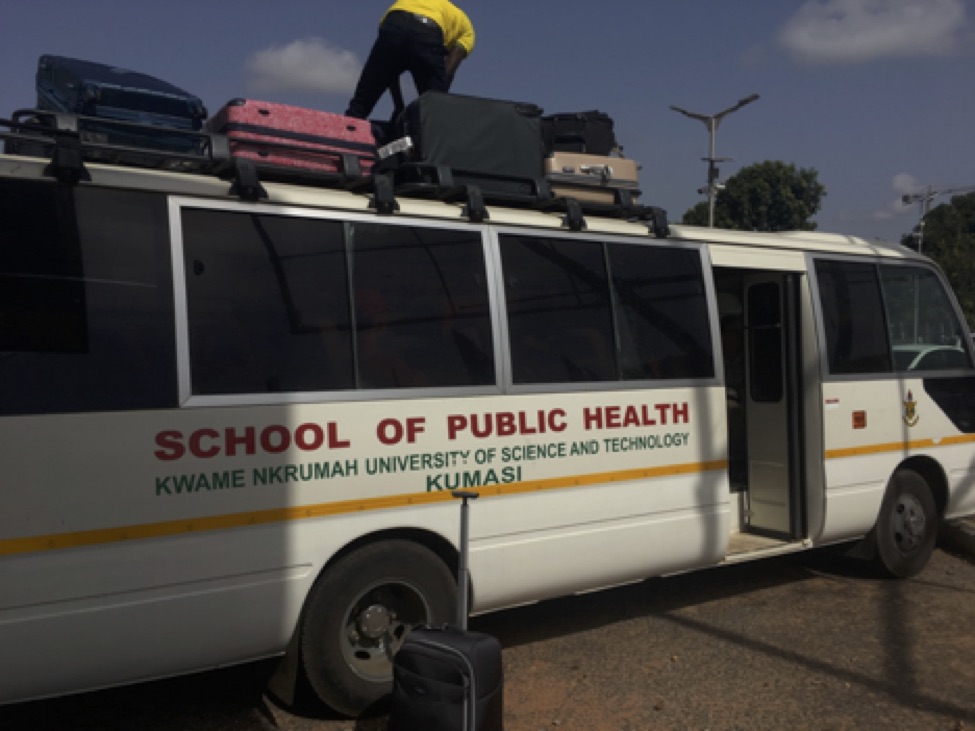

This morning, we had our official kickoff in the morning. It was a great meeting with Dr. Ellis, the Dean of School of Public Health. In the afternoon, professors from different schools delivered three lectures about the state of mental health, maternal and child nutrition, and health systems in Ghana.

The mental health lecture, given by Dr. Emma Adjaottor, was impressive and surprising. We are so lucky that we met one of the psychiatric physicians among a hundred across the country. The doctor frankly introduced mental health development in Ghana. Though they have lagged behind, they have made a lot of progress, with the number of psychiatrists in Ghana recently increasing from single digits to the double digits. Dr. Adjattor emphasized that the epidemiology of mental health in Ghana is nearly identical to the rest of the world, particularly in terms of incidence and prevalence, even though it is severely under-reported. The doctor explained that, although the epidemiology is the same, the terms used to describe these issues are often different, relying on more local ideas, such as spirits and witchcraft.

The mental health lecture, given by Dr. Emma Adjaottor, was impressive and surprising. We are so lucky that we met one of the psychiatric physicians among a hundred across the country. The doctor frankly introduced mental health development in Ghana. Though they have lagged behind, they have made a lot of progress, with the number of psychiatrists in Ghana recently increasing from single digits to the double digits. Dr. Adjattor emphasized that the epidemiology of mental health in Ghana is nearly identical to the rest of the world, particularly in terms of incidence and prevalence, even though it is severely under-reported. The doctor explained that, although the epidemiology is the same, the terms used to describe these issues are often different, relying on more local ideas, such as spirits and witchcraft.

The maternal and child nutrition lecture, given by Dr. Samuel Newton, was even more astonishing. Kangaroo mother care (KMC), in which a prematurely born infant is given constant skin-to-skin contact with the mother, is undergoing study in Ghana, and it has shown promising outcomes. Even with limited studies, KMC has been found to greatly increase the likelihood of survival even when using “surrogates,” such as grandmothers and even fathers. The professor also introduced another study that found that the application of oxytocin during the third stage of labor in mothers at risk of postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) greatly decreased the likelihood of PPH.

Finally, Professor Ellis Owusu-Dabo gave an extensive lecture covering the health systems of Ghana, which are logically and hierarchically managed, with administrations at the national, local, district, sub-district, and community levels. We also learned about the insurance program in Ghana. For formally employed workers, national insurance participation is mandatory, as it is funded by a mandatory tax on their income, like in many socialist countries. However, insurance coverage is a more complicated matter in Ghana, in which a very large proportion of the population is not formally employed and instead earn its living through trading and cash-paying jobs. For these people, other than the free public health services provided by the government such as malaria, tuberculosis, and HIV care, they must pay out of pocket for many other services.

Tomorrow will be the very first clinic visit, where we can observe children suffering from severe acute malnutrition. So the three of us in the nutrition group, Princess, Shihan, and Xuanjie, gathered together after dinner to discuss what we would ask the doctors and nurses during the visit. We agreed that, at first, we should ask whether we can take pictures to record. As for nutrition, we will ask how healthcare workers there define malnutrition.

To our knowledge, malnutrition standards are normally based on BMI, which is a composition of weight, height, and age-related data. We want to know whether Ghanaian healthcare professions use the same standards here, as well as how the local standards differ from the established WHO standards. Furthermore, we will ask for access to their local data sets. In addition to the results of malnutrition, we also want to know what the major causes of malnutrition are. We assumed that the principal cause is poverty, and based on this assumption, we want to ask them whether there are any welfare systems or NGOs helping to resolve the problem. We hope to find out what the clinics’ initial steps are to resolve malnutrition. Our last question involves how macronutrients are measured.

Tomorrow evening, we will give an open presentation in a local church to female market workers. We first planned to deliver the presentation in a discussion form, but considering the language barrier and other factors, we decided to give a speech, but we will ask simple questions. We thought that the scope of our research was not appropriate for local life in Ghana because much of the research was done in the U.S.; thus, it was necessary to get the input of local people. By asking them questions about what they eat on a daily basis, we want to make our research as appropriate as possible. In relation to our presentation, we will briefly introduce what nutrition is and explain the 6 essential nutrients through definitions and explanation. For example, when introducing carbohydrates, we will refer to fufu or banku, which are local main dishes basically consisting of starch. Also, we came up with an educational idea for the future. If we have a projector, we could possibly show some dishes to let the audience choose which is more nutritious, to provide general idea of a nutritious diet.

The mental health lecture, given by Dr. Emma Adjaottor, was impressive and surprising. We are so lucky that we met one of the psychiatric physicians among a hundred across the country. The doctor frankly introduced mental health development in Ghana. Though they have lagged behind, they have made a lot of progress, with the number of psychiatrists in Ghana recently increasing from single digits to the double digits. Dr. Adjattor emphasized that the epidemiology of mental health in Ghana is nearly identical to the rest of the world, particularly in terms of incidence and prevalence, even though it is severely under-reported. The doctor explained that, although the epidemiology is the same, the terms used to describe these issues are often different, relying on more local ideas, such as spirits and witchcraft.

The mental health lecture, given by Dr. Emma Adjaottor, was impressive and surprising. We are so lucky that we met one of the psychiatric physicians among a hundred across the country. The doctor frankly introduced mental health development in Ghana. Though they have lagged behind, they have made a lot of progress, with the number of psychiatrists in Ghana recently increasing from single digits to the double digits. Dr. Adjattor emphasized that the epidemiology of mental health in Ghana is nearly identical to the rest of the world, particularly in terms of incidence and prevalence, even though it is severely under-reported. The doctor explained that, although the epidemiology is the same, the terms used to describe these issues are often different, relying on more local ideas, such as spirits and witchcraft.