New research finds that works of literature, musical pieces, and social networks have a similar underlying structure that allows them to share large amounts of information efficiently.

By Erica K. Brockmeier

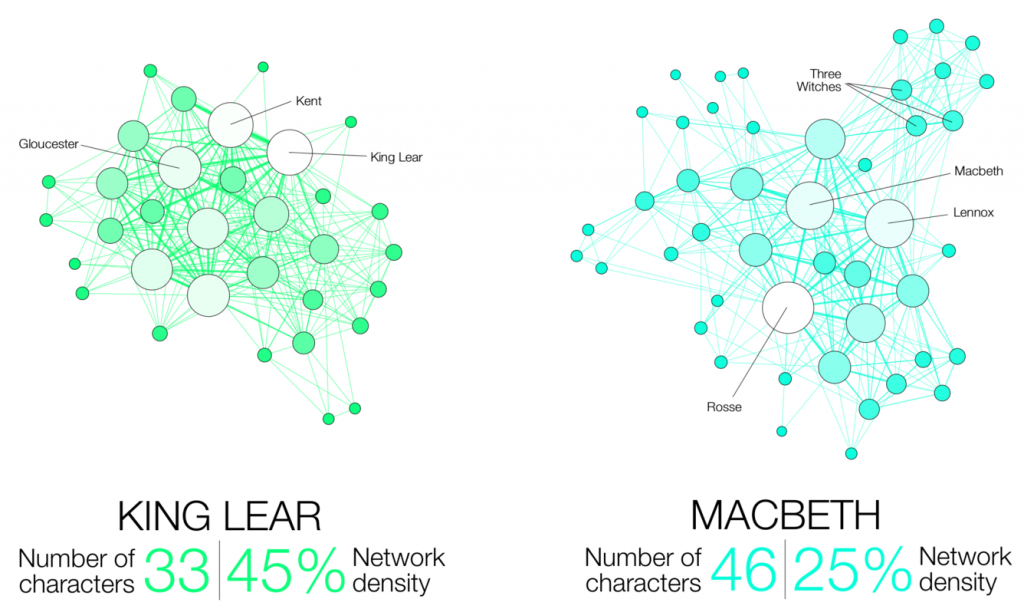

To an English scholar or avid reader, the Shakespeare Canon represents some of the greatest literary works of the English language. To a network scientist, Shakespeare’s 37 plays and the 884,421 words they contain also represent a massively complex communication network. Network scientists, who employ math, physics, and computer science to study vast and interconnected systems, are tasked with using statistically rigorous approaches to understand how complex networks, like all of Shakespeare, convey information to the human brain.

New research published in Nature Physics uses tools from network science to explain how complex communication networks can efficiently convey large amounts of information to the human brain. Conducted by postdoc Christopher Lynn, graduate students Ari Kahn and Lia Papadopoulos, and professor Danielle S. Bassett, the study found that different types of networks, including those found in works of literature, musical pieces, and social connections, have a similar underlying structure that allows them to share information rapidly and efficiently.

Technically speaking, a network is simply a statistical and graphical representation of connections, known as edges, between different endpoints, called nodes. In pieces of literature, for example, a node can be a word, and an edge can connect words when they appear next to each other (“my” — “kingdom” — “for” — “a” — “horse”) or when they convey similar ideas or concepts (“yellow” — “orange” — “red”).

The advantage of using network science to study things like languages, says Lynn, is that once relationships are defined on a small scale, researchers can use those connections to make inferences about a network’s structure on a much larger scale. “Once you define the nodes and edges, you can zoom out and start to ask about what the structure of this whole object looks like and why it has that specific structure,” says Lynn.

Building on the group’s recent study that models how the brain processes complex information, the researchers developed a new analytical framework for determining how much information a network conveys and how efficient it is in conveying that information. “In order to calculate the efficiency of the communication, you need a model of how humans receive the information,” he says.

Continue reading at Penn Today.