Penn Medicine researchers laud the early results for CAR T therapy in lupus patients, which point to broader horizons for the use of personalized cellular therapies.

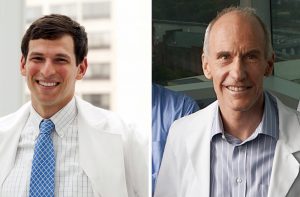

Engineered immune cells, known as CAR T cells, have shown the world what personalized immunotherapies can do to fight blood cancers. Now, investigators have reported highly promising early results for CAR T therapy in a small set of patients with the autoimmune disease lupus. Penn Medicine CAR T pioneer Carl June and Daniel Baker, a doctoral student in cell and molecular biology in the Perelman School of Medicine, discuss this development in a commentary published in Cell.

“We’ve always known that in principle, CAR T therapies could have broad applications, and it’s very encouraging to see early evidence that this promise is now being realized,” says June, who is the Richard W. Vague Professor in Immunotherapy in the department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine at Penn Medicine and director of the Center for Cellular Immunotherapies at the Abramson Cancer Center.

T cells are among the immune system’s most powerful weapons. They can bind to, and kill, other cells they recognize as valid targets, including virus-infected cells. CAR T cells are T cells that have been redirected, through genetic engineering, to efficiently kill specifically defined cell types.

CAR T therapies are created out of each patient’s own cells—collected from the patient’s blood, and then engineered and multiplied in the lab before being reinfused into the patient as a “living drug.” The first CAR T therapy, Kymriah, was developed by June and his team at Penn Medicine, and received Food & Drug Administration approval in 2017. There are now six FDA-approved CAR T cell therapies in the United States, for six different cancers.

From the start of CAR T research, experts believed that T cells could be engineered to fight many conditions other than B cell cancers. Dozens of research teams around the world, including teams at Penn Medicine and biotech spinoffs who are working to develop effective treatments from Penn-developed personalized cellular therapy constructs, are examining these potential new applications. Researchers say lupus is an obvious choice for CAR T therapy because it too is driven by B cells, and thus experimental CAR T therapies against it can employ existing anti-B-cell designs. B cells are the immune system’s antibody-producing cells, and, in lupus, B cells arise that attack the patient’s own organs and tissues.

This story is by Meagan Raeke. Read more at Penn Medicine News.

Carl June is a member of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group. Read more stories featuring June’s research here.