by Melissa Pappas

Each year, the Nemirovsky Engineering and Medicine Opportunity (NEMO) Prize, funded by Penn Health-Tech, awards $80,000 to a collaborative team of researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s Perelman School of Medicine and the School of Engineering and Applied Science for early-stage, interdisciplinary ideas.

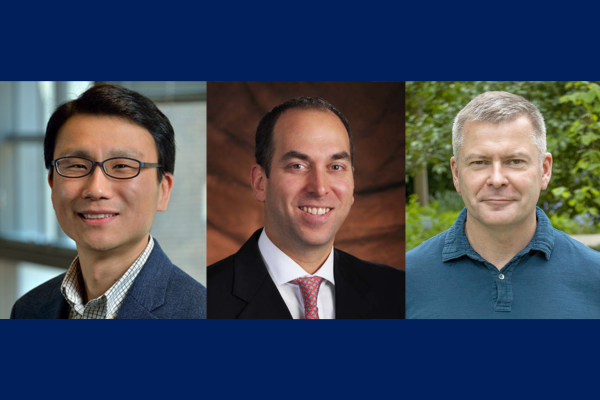

This year, the NEMO Prize has been awarded to Penn Engineering’s Daeyeon Lee, Russel Pearce and Elizabeth Crimian Heuer Professor in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Oren Friedman, Associate Professor of Clinical Otorhinolaryngology in the Perelman School of Medicine, and Sergei Vinogradov, Professor in the Department of Biochemistry and Biophysics in the Perelman School of Medicine and the Department of Chemistry in the School of Arts & Sciences. Together, they are developing a new therapy that improves the survival and success of soft-tissue grafts used in reconstructive surgery.

More than one million people receive soft-tissue reconstructive surgery for reasons such as tissue trauma, cancer or birth defects. Autologous tissue transplants are those where cells and tissue such as fat, skin or cartilage are moved from one part of a patient’s body to another. As the tissue comes from the patient, there is little risk of transplant rejection. However, nearly one in four autologous transplants fail due to tissue hypoxia, or lack of oxygen. When transplants fail the only corrective option is more surgery. Many techniques have been proposed and even carried out to help oxygenate soft tissue before it is transplanted to avoid failures, but current solutions are time consuming and expensive. Some even have negative side effects. A new therapy to help oxygenate tissue quickly, safely and cost-effectively would not only increase successful outcomes of reconstructive surgery, but could be widely applied to other medical challenges.

The therapy proposed by this year’s NEMO Prize recipients is a conglomerate or polymer of microparticles that can encapsulate oxygen and disperse it in sustainable and controlled doses to specific locations over periods of time up to 72 hours. This gradual release of oxygen into the tissue from the time it is transplanted to the time it functionally reconnects to the body’s vascular system is essential to keeping the tissue alive.

“The microparticle design consists of an oxygenated core encapsulated in a polymer shell that enables the sustained release of oxygen from the particle,” says Lee. “The polymer composition and thickness can be controlled to optimize the release rate, making it adaptable to the needs of the hypoxic tissue.”

These life-saving particles are designed to be integrated into the tissue before transplantation. However, because they exist on the microscale, they can also be applied as a topical cream or injected into tissue after transplantation.

“Because the microparticles are applied directly into tissues topically or by interstitial injection (rather than being administered intravenously), they surpass the need for vascular channels to reach the hypoxic tissue,” says Friedman. “Their micron-scale size combined with their interstitial administration, minimizes the probability of diffusion away from the injury site or uptake into the circulatory system. The polymers we plan to use are FDA approved for sustained-release drug delivery, biocompatible and biodegrade within weeks in the body, presenting minimal risk of side effects.”

The research team is currently testing their technology in fat cells. Fat is an ideal first application because it is minimally invasive as an injectable filler, making it versatile in remodeling scars and healing injury sites. It is also the soft tissue type most prone to hypoxia during transplant surgeries, increasing the urgency for oxygenation therapy in this particular tissue type.

Read the full story in Penn Engineering Today.

Daeyeon Lee and Sergei Vinogradov are members of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group.

Speaker: Glenna Wink Foight, Ph.D.

Speaker: Glenna Wink Foight, Ph.D. Speaker:

Speaker: