by Scott Harris

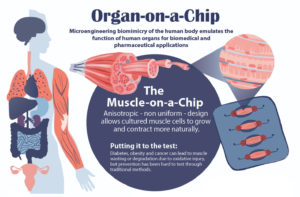

If you’d read about it in a science fiction novel, you might not have believed it. Human organs and organ systems — from lungs to blood vessels to blinking eyes — bio-miniaturized and stored on a plastic chip no larger than a matchbook.

But that’s the breathing, blinking reality at the Biologically Inspired Engineering Systems (BIOLines) Laboratory in the Department of Bioengineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania, a bona fide pioneer of what is now widely known as “organ-on-a-chip” technology. Proponents hope these devices can one day help scientists around the world learn more about the body’s inner workings and ultimately improve disease prevention and treatment.

“The century-old practice of cell culture is to grow living cells isolated from the human body in hard plastic dishes and keep them bathed in copious amounts of culture media under static conditions, and that is drastically different than the complex, dynamic environment of native tissues in which these cell reside,” said Dan Dongeun Huh, Ph.D., BIOLines’ principal investigator and an associate professor of Bioengineering in Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science. “What makes this organ-on-a-chip technology so unique and powerful is that it enables us to reverse-engineer living human tissues using microengineered devices and mimic their intricate biological interactions and physiological functions in ways that have not been possible using traditional cell culture techniques. This represents a major advance in our ability to model and understand the inner workings of complex physiological systems in the human body.”

Generally speaking, organ-on-a-chip devices are made of clear silicone rubber — the same material used to make contact lenses — and can vary in size and design. Embedded within are microfabricated three-dimensional chambers lined with different human cell types, arranged and propagated to ultimately form a structure complex enough to actually mimic the essential elements of a functioning organ.

With partners at the Perelman School of Medicine, BIOLines recently developed a newer variation of the organ-on-a-chip: one that replicates the interface between maternal tissue and the cells of the placenta at the critical moments in early pregnancy when the embryo is implanting in the uterus. Huh and Penn Medicine physicians led a study using the “implantation-on-a-chip” to observe things that would otherwise have been virtually unobservable.

The study findings appeared this spring in the journal Nature Communications.

Continue reading at Penn Medicine News.