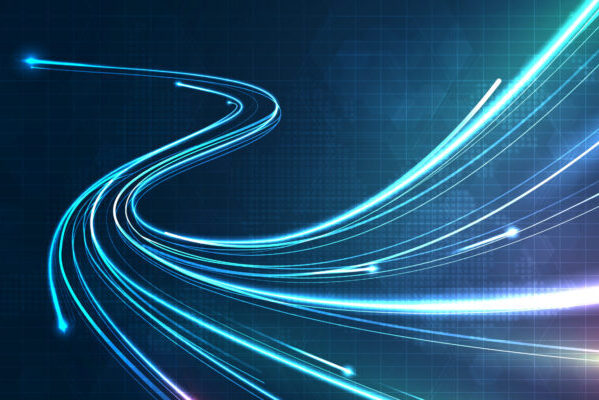

For bioengineers today, light does more than illuminate microscopes. Stimulating cells with light waves, a field known as optogenetics, has opened new doors to understanding the molecular activity within cells, with potential applications in drug discovery and more.

Thanks to recent advances in optogenetic technology, much of which is cheap and open-source, more researchers than ever before can construct arrays capable of running multiple experiments at once, using different wavelengths of light. Computing languages like Python allow researchers to manipulate light sources and precisely control what happens in the many “wells” containing cells in a typical optogenetic experiment.

However, researchers have struggled to simultaneously gather data on all these experiments in real time. Collecting data manually comes with multiple disadvantages: transferring cells to a microscope may expose them to other, non-experimental sources of light. The time it takes to collect the data also makes it difficult to adjust metabolic conditions quickly and precisely in sample cells.

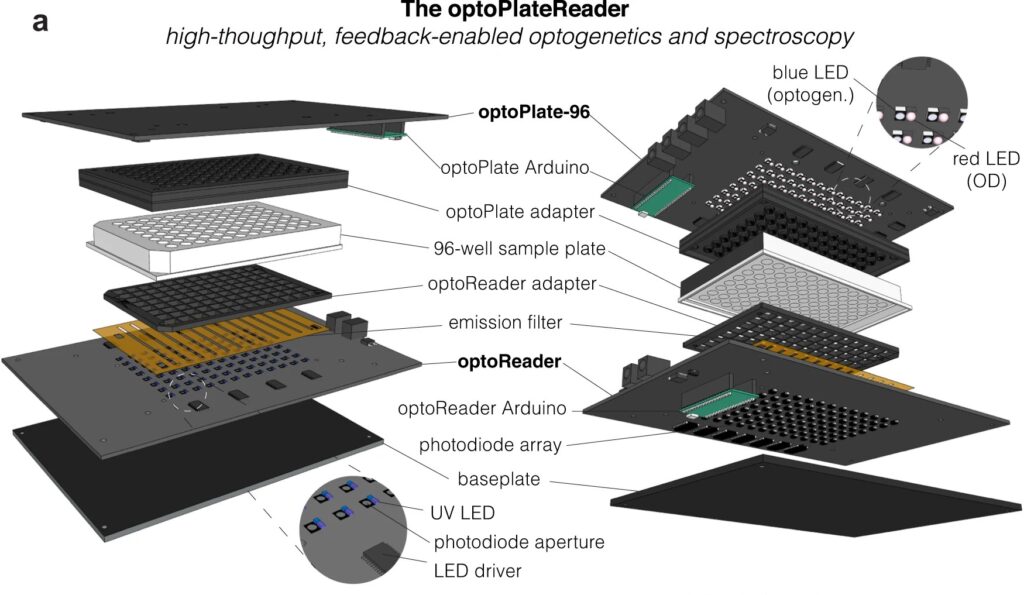

Now, a team of Penn Engineers has published a paper in Communications Biology, an open access journal in the Nature portfolio, outlining the first low-cost solution to this problem. The paper describes the development of optoPlateReader (or oPR), an open-source device that addresses the need for instrumentation to monitor optogenetic experiments in real time. The oPR could make possible features such as automated reading, writing and feedback in microwell plates for optogenetic experiments.

The paper follows up on the award-winning work of six University of Pennsylvania alumni — Saachi Datta, M.D. Candidate at Stanford School of Medicine; Juliette Hooper, Programmer Analyst in Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine; Gabrielle Leavitt, M.D. Candidate at Temple University; Gloria Lee, graduate student at Oxford University; Grace Qian, Drug Excipient and Residual Analysis Research Co-op at GSK; and Lana Salloum, M.D. Candidate at Albert Einstein College of Medicine — who claimed multiple prizes at the 2021 International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition (iGEM) as Penn undergraduates.

The International Genetically Engineered Machine Competition (or iGEM) is the largest synthetic biology community and the premiere synthetic biology competition for both university and high school students from around the world. Hundreds of interdisciplinary teams of students compete annually, combining molecular biology techniques and engineering concepts to create novel biological systems and compete for prizes and awards through oral presentations and poster sessions.

The optoPlateReader was initially developed by Penn’s 2021 iGEM team, combining a light-stimulation device with a plate reader. At the iGEM competition, the invention took home Best Foundational Advance (best in track), Best Hardware (best from all undergraduate teams), and Best Presentation (best from all undergraduate teams), as well as a Gold Medal Distinction and inclusion in the Top 10 Overall and Top 10 Websites lists. (Read more about the 2021 iGEM team on the BE Blog.)

The original iGEM project focused on the design, construction, and testing of the hardware and software that make up the oPR, the focus of the new paper. After iGEM concluded, the team showed that the oPR could be used with real biological samples, such as cultures of bacteria. This work demonstrated that the oPR could be applied to real research questions, a necessary precursor to publication, and that the device could simultaneously monitor and manipulate living samples.

The main application for the oPR is in metabolic production (such as the creation of pharmaceuticals and bio-fuels). The oPR is able to issue commands to cells via light but can also take live readings about their current state. In the oPR, certain colors of light cause cells to carry out different tasks, and optical measurements give information on growth rates and protein production rates.

In this way, the new device is able to support production processes that can adapt in real time to what cells need, altering their behavior to maximize yield. For example, if an experiment produces a product that is toxic to cells, the oPR could instruct those cells to “turn on” only when the population of cells is dense and “turn off” when the concentration of that product becomes toxic and the cellular population needs to recover. This ability to pivot in real time could assist industries that rely on bioproduction.

The main challenges in developing this device were in incorporating the many light emitting diodes (LEDs) and sensors into a tiny space, as well as insulating the sensors from the nearby LEDs to ensure that the measured light came from the sample and not from the instrument itself. The team also had to create software that could coordinate the function of nearly 100 different sets of LEDs and sensors. Going forward, the team hopes to spread the word about the open-source oPR to other researchers studying metabolic production to enable more efficient research.

Lukasz Bugaj, Assistant Professor in Bioengineering and senior author of the paper, served as the team’s mentor along with Brian Chow, formerly an Associate Professor in Bioengineering and a founding member of the iGEM program at MIT, and Jose Avalos, Associate Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Princeton University.

Key to the project’s development was the guidance of Bioengineering graduate students Will Benman, David Gonzalez Martinez, and Gabrielle Ho, as well as that of Saurabh Malani, a graduate student at Princeton University.

Much of the original work was conducted in Penn Bioengineering’s Stephenson Foundation Educational Laboratory & Bio-MakerSpace, with important contributions made by Michael Patterson, Director of Educational Laboratories in Bioengineering, and Sevile Mannickarottu, Director of Technological Innovation and Entrepreneurship in Penn Engineering’s Entrepreneurship Program.

Read “High-throughput feedback-enabled optogenetic stimulation and spectroscopy in microwell plates” in Communications Biology.

This project was supported by the Department of Bioengineering, the School of Engineering and Applied Science, and the Office of the Vice Provost for Research (OVPR), and by funding from the National Institute of Health (NIH), the National Science Foundation (NSF), and the Department of Energy (DOE).

The iGEM program was created at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 2003. Read stories in the BE Blog featuring recent Penn iGEM teams here.