by Meagan Raeke

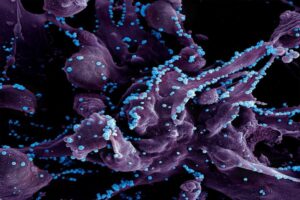

For most of modern medicine, cancer drugs have been developed the same way: by designing molecules to treat diseased cells. With the advent of immunotherapy, that changed. For the first time, scientists engineered patients’ own immune systems to recognize and attack diseased cells.

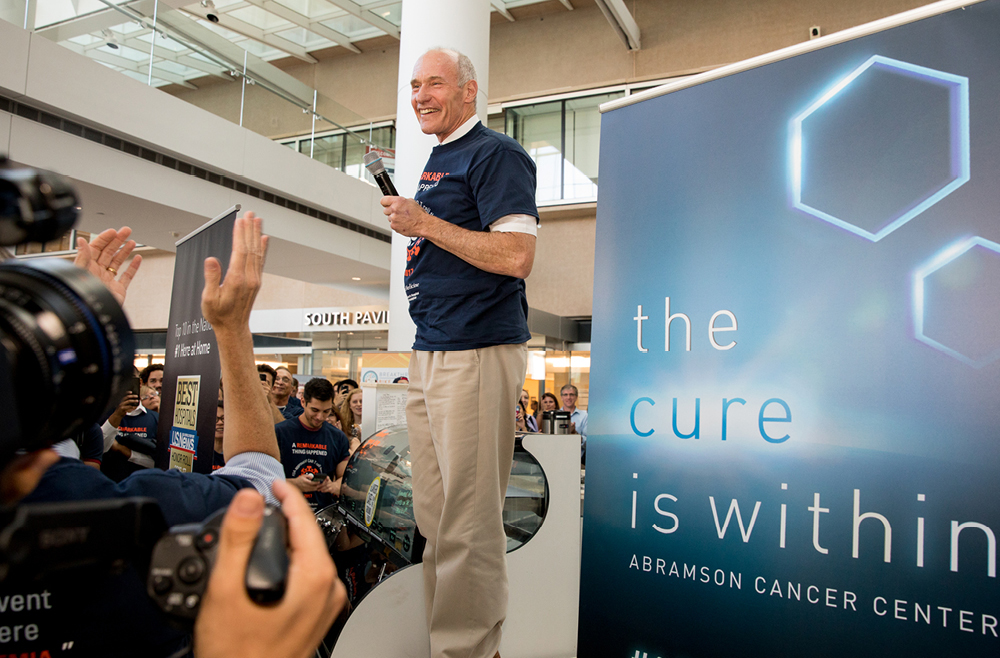

One of the best examples of this pioneering type of medicine is CAR T cell therapy. Invented in the Perelman School of Medicine by Carl June, the Richard W. Vague Professor in Immunotherapy, CAR T cell therapy works by collecting T cells from a patient, modifying those cells in the lab so that they are designed to destroy cancerous cells, and reinfusing them into the patient. June’s research led to the first FDA approval for this type of therapy, in 2017. Six different CAR T cell therapies are now approved to treat various types of blood cancers. Carl June, at the flash mob celebration of the FDA approval of the CAR T cell therapy he developed, in August 2017. (Image: Courtesy of Penn Medicine Magazine)

CAR T cell therapy holds the potential to help millions more patients—if it can be successfully translated to other conditions. June and colleagues, including Daniel Baker, a fourth-year doctoral student in the Cell and Molecular Biology department, discuss this potential in a perspective published in Nature.

In the piece, June and Baker highlight other diseases that CAR T cell therapy could be effective.

“CAR T cell therapy has been remarkably successful for blood cancers like leukemias and lymphomas. There’s a lot of work happening here at Penn and elsewhere to push it to other blood cancers and to earlier stage disease, so patients don’t have to go through chemo first,” June says. “Another big priority is patients with solid tumors because they make up the vast majority of cancer patients. Beyond cancer, we’re seeing early signs that CAR T cell therapy could work in autoimmune diseases, like lupus.”

As for which diseases to pursue as for possible future treatment, June says, “essentially it boils down to two questions: Can we identify a population of cells that are bad? And can we target them specifically? Whether that’s asthma or chronic diseases or lupus, if you can find a bad population of cells and get rid of them, then CAR T cells could be therapeutic in that context.”

“What’s exciting is it’s not just theoretical at this point. There have been clinical reports in other autoimmune diseases, including myasthenia gravis and inflammatory myopathy,” Baker says. “But we are seeing early evidence that CAR T cell therapy will be successful beyond cancer. And it’s really opening the minds of people in the field to think about how else we could use CAR T. For example, there’s some pioneering work at Penn from the Epstein lab for heart failure. The idea is that you could use CAR T cells to get rid of fibrotic tissue after a cardiac injury, and potentially restore the damage following a heart attack.”

Baker adds, “there’s no question that over the last decade, CAR T cell therapy has revolutionized cancer. I’m hoping to play a role in bringing these next generation therapies to patients and make a real impact over the next decade. I think there’s potential for cell therapy to be a new pillar of medicine at large, and not just a new pillar of oncology.”

Read the full story at Penn Medicine Today.

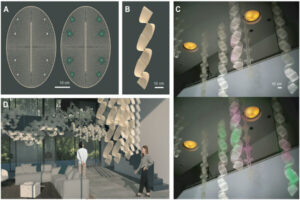

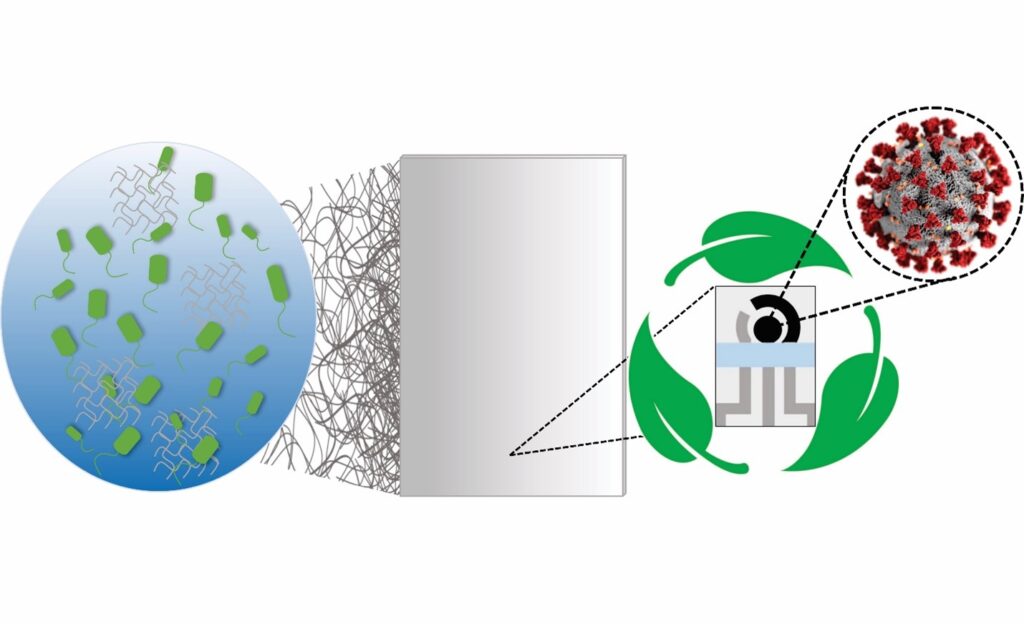

A research team led by engineers at the

A research team led by engineers at the