by Marilyn Perkins

Neuroscientists frequently say that neural activity ‘represents’ certain phenomena, PIK Professor Konrad Kording and postdoc Ben Baker led a study that took a philosophical approach to tease out what the term means.

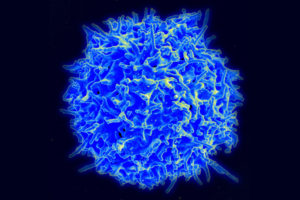

One of neuroscience’s greatest challenges is to bridge the gaps between the external environment, the brain’s internal electrical activity, and the abstract workings of behavior and cognition. Many neuroscientists rely on the word “representation” to connect these phenomena: A burst of neural activity in the visual cortex may represent the face of a friend or neurons in the brain’s memory centers may represent a childhood memory.

But with the many complex relationships between mind, brain, and environment, it’s not always clear what neuroscientists mean when they say neural activity “represents” something. Lack of clarity around this concept can lead to miscommunication, flawed conclusions, and unnecessary disagreements.

To tackle this issue, an interdisciplinary paper takes a philosophical approach to delineating the many aspects of the word “representation” in neuroscience. The work, published in Trends in Cognitive Sciences, comes from the lab of Konrad Kording, a Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor and senior author on the study whose research lies at the intersection of neuroscience and machine learning.

“The term ‘representation’ is probably one of the most common words in all of neuroscience,” says Kording, who has appointments in the Perelman School of Medicine and School of Engineering and Applied Science. “But it might mean something very different from one professor to another.”

Read the full story in Penn Today.

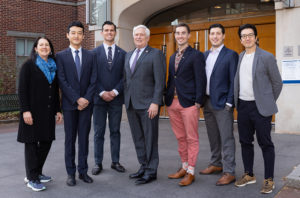

Konrad Kording is a Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor with joint appointments in the Department of Neuroscience the Perelman School of Medicine and in the Department of Bioengineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

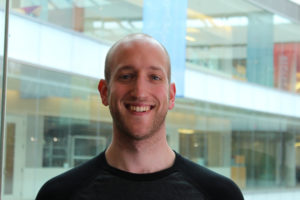

Ben Baker is a postdoctoral researcher in the Kording lab and a Provost Postdoctoral Fellow. Baker received his Ph.D. in philosophy from Penn.

Also coauthor on the paper is Benjamin Lansdell, a data scientist in the Department of Developmental Neurobiology at St. Jude Children’s Hospital and former postdoctoral researcher in the Kording lab.

Funding for this study came from the National Institutes of Health (awards 1-R01-EB028162-01 and R01EY021579) and the University of Pennsylvania Office of the Vice Provost for Research.