by

When trying to choose between two career paths—dentistry and engineering—Kyle Vining decided ‘Why not both?’ Vining joined Penn in July 2022 and is jointly appointed in the School of Dental Medicine and the School of Engineering and Applied Science.

“During my training, I saw that there was overlap where I could do clinical work and science at the same time, and so that’s what I’ve been doing ever since,” Vining says. “As far back as middle school, I always wanted to be a biomedical engineer, and then the clinical side became interesting to me because I didn’t want to only do the theoretical or research side of things. I also wanted the hands-on, practical interaction of a skilled profession.”

The benefits of a dual career: Variety and opportunities to give back

Vining finds that wearing two hats offers the best of both worlds: opportunities to help both individual patients and to contribute to scientific and clinical progress.

“On the dentistry side, what I enjoy is getting to see patients, solving clinical problems, and trying to perform the best treatment I can; it has this rapid pace, which is kind of exciting and keeps you motivated,” Vining says. “And then research allows me to explore my interests and think about making an impact more broadly, not just in dentistry, but in medicine or in the world in general.”

Vining says dental school was demanding, yet a good time to explore his varied interests. He says he’d encourage others to pursue dentistry with an interdisciplinary approach. “Having exposure to different fields or different knowledge while you’re a student is really good for students and the profession in general,” he says.

The path towards a dual career

Vining first delved into research as a biomedical engineering undergraduate at Northwestern University. “I had the opportunity to work in a materials science lab studying the chemistry of surfaces. We would use molecules to modify the properties and surfaces that environments or cells could interact with,” he says.

Then, as a student at the University of Minnesota School of Dentistry, Vining realized that this same materials science research had many applications in dentistry. While in dental school, Vining conducted independent research in a materials science lab and also took the opportunity to do a yearlong fellowship in a cell and developmental biology lab at the National Institutes of Health.

Vining credits this fellowship with launching him towards a Ph.D., which he completed in bioengineering at Harvard in 2020. After earning his Ph.D., Vining conducted research at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute prior to joining Penn.

Using biomaterials to understand how cells and tissues interact

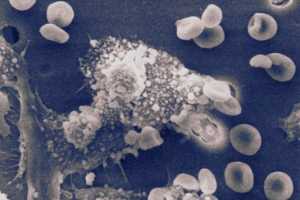

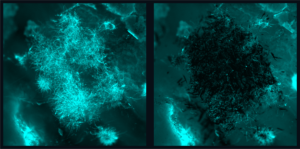

Vining’s research at Penn aims to understand how the biophysical properties of materials impact cellular processes such as inflammation and fibrosis.

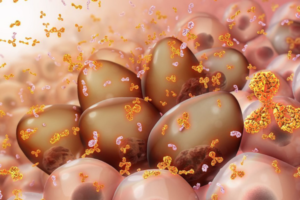

“Fibrosis is a physical change in tissues that produces a scar-like matrix that can inhibit healing, impair cancer treatment, and in general is not compatible with tissues regeneration,” Vining says. “There’s been a lot of effort on antifibrotic drugs, but we’re trying to look at fibrosis a little bit differently. Instead of directly inhibiting fibrosis, we’re trying to understand its consequences for the immune system because the immune system can be hijacked and become detrimental for your tissues.”

Through a better understanding the feedback loop between fibrotic tissue and the immune system, Vining hopes to design interventions to facilitate wound healing and tissue remodeling during restorative dental procedures and for treating diseases including head and neck cancer.

He’s also investigating how biomaterials like the resin used in tooth fillings interact with dental tissues. “Dental fillings rely on decades-old technologies that have been grandfathered in and contain toxic monomers that are not safe for biological systems,” Vining says. “We found a biocompatible resin chemistry that supports cells in vitro, and we’re trying to apply this to new types of dental fillings that promote repair or generation of dental tissues.”

Fostering interdisciplinary collaborations at Penn

Vining was recruited to be part of the Center for Innovation & Precision Dentistry (CiPD), the joint center of Penn Dental Medicine and Penn Engineering.

“Dr. Vining is an ideal fit for the vision and mission of the CiPD,” says Penn Dental’s Hyun (Michel) Koo, co-founder and co-director of the CiPD. “With a secondary appointment in the School of Engineering, he will be instrumental in continuing to strengthen our engineering collaborations and teaching our students to work across disciplines to advance research, training, and entrepreneurship in this realm.”

Ultimately, Vining says it was Penn’s scientific community and the opportunities for interdisciplinary collaborations that drew him here.

“It was very apparent that there were a lot of potential research paths to pursue here and a lot of opportunities for collaborations,” Vining says. “One of the most exciting things for me so far has been meeting with faculty, whether it’s at Penn Medicine, the School of Engineering, Wharton, Penn Dental, or the Veterinary School. These meetings have already opened up new projects and collaborations.”

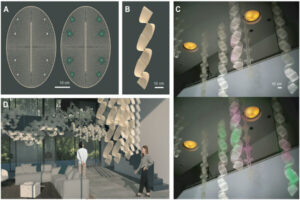

One such collaboration is with Michael Mitchell, associate professor of bioengineering. The pair were awarded the second annual IDEA (Innovation in Dental Medicine and Engineering to Advance Oral Health) Prize in May 2023 to kickstart a project exploring the potential for using lipid nanoparticles to treat dental decay.

The collaboration sparked when Vining saw Mitchell present on a new technology that uses lipid nanoparticles to bind and target bone marrow cells at the 2022 CiPD first annual symposium. “It got me thinking because the dentin inside of teeth is a mineralized tissue very similar to bone, and the pulp inside the dentin is analogous to bone marrow tissue,” Vining says.

Read the full story in Penn Today.

Vining and Koo are members of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group.

Carlos Armando Aguila, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center of Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, advised by

Carlos Armando Aguila, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center of Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, advised by  Joseph Lance Victoria Casila is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of

Joseph Lance Victoria Casila is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of  Trevor Chan is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of

Trevor Chan is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of  Rakan El-Mayta is an incoming Ph.D. student in the lab of

Rakan El-Mayta is an incoming Ph.D. student in the lab of  Austin Jenk is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Austin Jenk is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Jiageng Liu is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Jiageng Liu is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Alexandra Neeser is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Alexandra Neeser is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  William Karl Selboe Ojemann, a Ph.D. Student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics directed by

William Karl Selboe Ojemann, a Ph.D. Student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics directed by  Savan Patel (BSE Class of 2023) conducted research in the lab of

Savan Patel (BSE Class of 2023) conducted research in the lab of  David E. Reynolds, a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of

David E. Reynolds, a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of  Andre Roots is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Andre Roots is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Emily Sharp, a second year Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of

Emily Sharp, a second year Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of  Nat Thurlow is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Nat Thurlow is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Maggie Wagner, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member in the labs of

Maggie Wagner, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member in the labs of