New Data Analysis Methods

Like many other fields, biomedical research is experiencing a data explosion. Some estimates suggest that the amount of data generated from the health sciences is now doubling every eighteen months, and experts expect it to double every seventy-three days by 2020. One challenge that researchers face is how to meaningfully analyze this data tsunami.

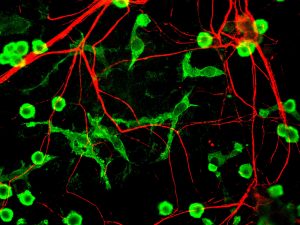

The challenge of interpreting data occurs at all scales, and a recent collaboration shows how new approaches can allow us to handle the volumes of data emerging at the level of individual cells to infer more about how biology “works” at this level. Wharton Statistics Department researchers Mo Huang and Jingshu Wang (PhD Student and Postdoctoral Researcher, respectively) collaborated with Arjun Raj’s lab in Bioengineering and published their findings in recent issues of Nature Methods and Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. One study focused on a de-noising technique called SAVER to provide more precise data from single cell experiments and significantly improves the ability to detect trends in a dataset, similar to how increasing sample size helps improve the ability to determine differences between experimental groups. The second method, termed DESCEND, creates more accurate characterization of gene expression that occur in individual cells. Together these two methods will improve data collection for biologists and medical professionals working to diagnose, monitor, and treat diseased cells.

Dr. Raj’s team contributed data to the cause and acted as consultants on the biological aspects of this research. Further collaboration involved Mingyao Li, PhD, Professor of Biostatistics at the Perelman School of Medicine, and Nancy Zhang, PD, Professor Statistics at the Wharton School. “We are so happy to have had the chance to work with Nancy and Mingyao on analyzing single cell data,” said Dr. Raj. “The things they were able to do with our data are pretty amazing and important for the field.”

Advancements in Biomaterials

This blog features many new biomaterials techniques and substances, and there are several exciting new developments to report this week. First, the journal of Nature Biomedical Engineering published a study announcing a new therapy to treat or even eliminate lung infections, such as those acquired while in hospital or as the result of cystic fibrosis, which are highly common and dangerous. Researchers identified and designed viruses to target and kill the bacteria which causes these infections, but the difficulty of administering them to patients has proven prohibitive. This new therapy, developed by researchers at the Georgia Institute of Technology, is administered as a dry powder directly to the lungs and bypasses many of the delivery problems appearing in past treatments. Further research on the safety of this method is required before clinical trials can begin.

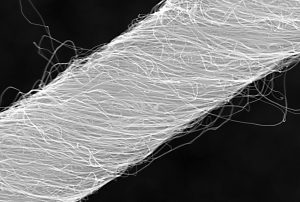

A team at Harvard University published another recent study in Nature Biomedical Engineering announcing their creation of a tissue-engineered scale model of the left human heart ventricle. This model is made from degradable fibers that simulate the natural fibers of heart tissue. Lead investigator Professor Kevin Kit Parker, PhD, and his team eventually hope to build specific models culled from patient stem cells to replicate the features of that patient’s heart, complete with the patient’s unique DNA and any heart defects or diseases. This replica would allow researchers and clinicians to study and test various treatments before applying them to a specific patient.

Lastly, researchers at the Tufts University School of Engineering published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences on their creation of flexible magnetic composites that respond to light. This material is capable of macroscale motion and is extremely flexible, allowing its adaptation into a variety of substances such as sponges, film, and hydrogels. Author and graduate student Meg Li explained that this material differs from similar substances in its complexity; for example, in the ability for engineers to dictate specific movements, such as toward or away from the light source. Co-author Fiorenzo Omenetto, PhD, suggests that with further research, these movements could be controlled at even more specific and detailed levels.

CFPS: Getting Closer to “On Demand” Medicine

A recent and growing trend in medicine is the move towards personalized or “on demand” medicine, allowing for treatment customized to specific patients’ needs and situations. One leading method is Cell-Free Protein Synthesis (CFPS), a way of engineering cellular biology without using actual cells. CFPS is used to make substances such as medicine, vaccines, and chemicals in a sustainable and portable way. One instance if the rapid manufacture of insulin to treat diabetic patients. Given that many clinics most in need of such substances are found in remote and under-served locations far away from well-equipped hospitals and urban infrastructure, the ability to safely and quickly create and transport these vital substances to patients is vitally important.

The biggest limiting factor to CFPS is difficulty of replicating Glycosylation, a complex modification that most proteins undergo. Glycosylation is important for proteins to exert their biological function, and is very difficult to synthetically duplicate. Previously, achieving successful Glycosylation was a key barrier in CFPS. Fortunately, Matthew DeLisa, PhD, the Williams L. Lewis Professor of Engineering at Cornell University and Michael Jewett, PD, Associate Professor of Chemical and Biological Engineering at Northwestern University, have created a “single-pot” glycoprotein biosynthesis that allows them to make these critical molecules very quickly. The full study was recently published in Nature Communications. With this new method, medicine is one step closer to being fully “on demand.”

People and Places

The Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE) interviewed our own Penn faculty member Danielle Bassett, PhD, the Edwardo D. Glandt Faculty Fellow and Associate Professor in Bioengineering, for their website. Dr. Bassett, who shares a joint appointment with Electrical Systems Engineering (ESE) at Penn, has published groundbreaking research in Network Neuroscience, Complex Systems, and more. In the video interview (below), Dr. Bassett discusses current research trends in neuroscience and their applications in medicine.

Finally, a new partnership between Case Western Reserve University and Cleveland Clinic seeks to promote education and research in biomedical engineering in the Cleveland area. Cleveland Clinic Lerner Research Institute‘s Chair of Biomedical Engineering, Geoff Vince, PhD, sees this as an opportunity to capitalize on the renown of both institutions, building on the region’s already stellar reputation in the field of BME. Dozens of researchers from both institutions will have the opportunity to collaborate in a variety of disciplines and projects. In addition to professional academics and medical doctors, the leaders of this new partnership hope to create an atmosphere that can benefit all levels of education, all the way down to high school students.

Danielle Bassett, PhD

Danielle Bassett, PhD