by Melissa Pappas

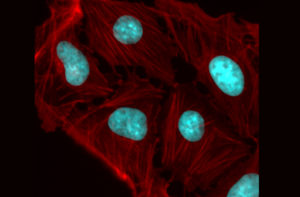

Most organisms have proteins that react to light. Even creatures that don’t have eyes or other visual organs use these proteins to regulate many cellular processes, such as transcription, translation, cell growth and cell survival.

The field of optogenetics relies on such proteins to better understand and manipulate these processes. Using lasers and genetically engineered versions of these naturally occurring proteins, known as probes, researchers can precisely activate and deactivate a variety of cellular pathways, just like flipping a switch.

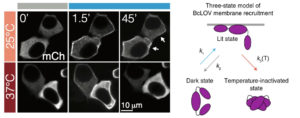

Now, Penn Engineering researchers have described a new type of optogenetic protein that can be controlled not only by light, but also by temperature, allowing for a higher degree of control in the manipulation of cellular pathways. The research will open new horizons for both basic science and translational research.

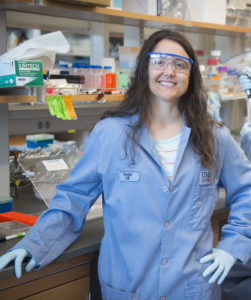

Lukasz Bugaj, Assistant Professor in Bioengineering (BE), Bomyi Lim, Assistant Professor in Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, Brian Chow, Associate Professor in BE, and graduate students William Benman in Bugaj’s lab, Hao Deng in Lim’s lab, and Erin Berlew and Ivan Kuznetsov in Chow’s lab, published their study in Nature Chemical Biology. Arndt Siekmann, Associate Professor of Cell and Developmental Biology at the Perelman School of Medicine, and Caitlyn Parker, a research technician in his lab, also contributed to this research.

The team’s original aim was to develop a single-component probe that would be able to manipulate specific cellular pathways more efficiently. The model for their probe was a protein called BcLOV4, and through further investigation of this protein’s function, they made a fortuitous discovery: that the protein is controlled by both light and temperature.

Read more in Penn Engineering Today.