by Meagan Raeke

The development of any type of second cancer following CAR T cell therapy is a rare occurrence, as found in an analysis of more than 400 patients treated at Penn Medicine, researchers from the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania reported today in Nature Medicine. The team also described a single case of an incidental T cell lymphoma that did not express the CAR gene and was found in the lymph node of a patient who developed a secondary lung tumor following CAR T cell therapy.

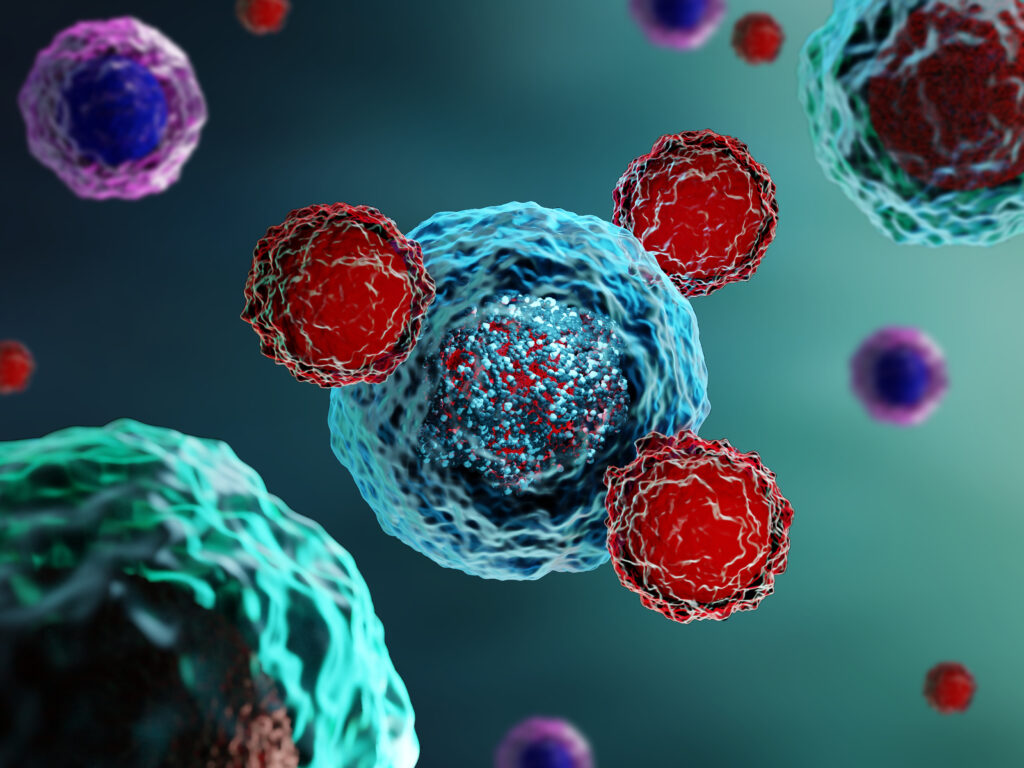

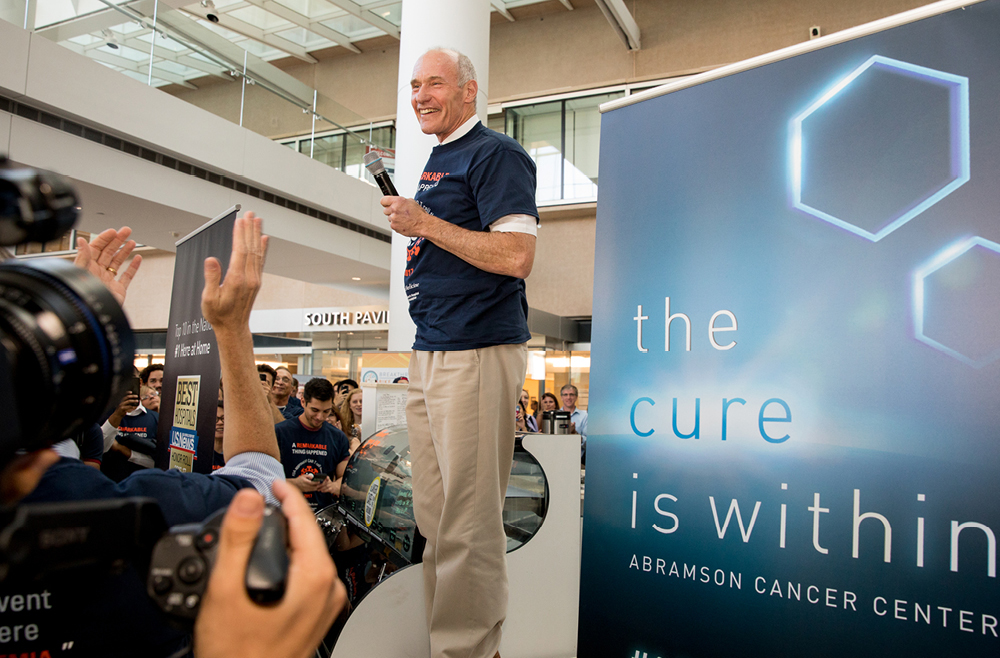

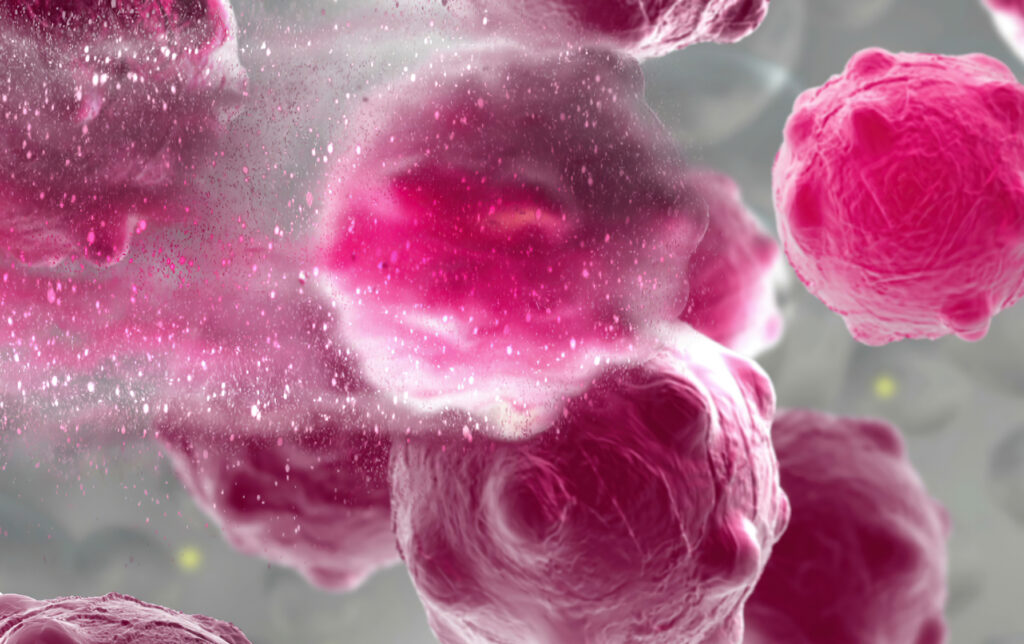

CAR T cell therapy, a personalized form of immunotherapy in which each patient’s T cells are modified to target and kill their cancer cells, was pioneered at Penn. More than 30,000 patients with blood cancers in the United States—many of whom had few, if any, remaining treatment options available—have been treated with CAR T cell therapy since the first such therapy was approved in 2017. Some of the earliest patients treated in clinical trials have gone on to experience long-lasting remissions of a decade or more.

Secondary cancers, including T cell lymphomas, are a known, rare risk of several types of cancer treatment, including chemotherapy, radiation, and stem cell transplant. CAR T cell therapy is currently only approved to treat blood cancers that have relapsed or stopped responding to treatment, so patients who receive CAR T cell therapies have already received multiple other types of treatment and are facing dire prognoses.

In November 2023, the FDA announced an investigation into several reported cases of secondary T cell malignancies, including CAR-positive lymphoma, in patients who previously received CAR T cell therapy products. In January 2024, the FDA began requiring drugmakers to add a safety label warning to CAR T cell products. While the FDA review is still ongoing, it remains unclear whether the secondary T cell malignancies were caused by CAR T cell therapy.

As a leader in CAR T cell therapy, Penn has longstanding, clearly established protocols to monitor each patient both during and after treatment – including follow-up for 15 years after infusion – and participates in national reporting requirements and databases that track outcomes data from all cell therapy and bone marrow transplants.

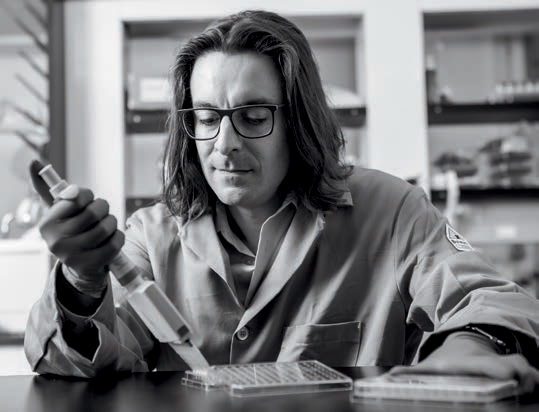

“When this case was identified, we did a detailed analysis and concluded the T cell lymphoma was not related to the CAR T cell therapy. As the news of other cases came to light, we knew we should go deeper, to comb through our own data to better understand and help define the risk of any type of secondary cancer in patients who have received CAR T cell products,” said senior author Marco Ruella, MD, an assistant professor of Hematology-Oncology and Scientific Director of the Lymphoma Program. “What we found was very encouraging and reinforces the overall safety profile for this type of personalized cell therapy.”

Read the full story in Penn Medicine News.

Marco Ruella is Assistant Professor of Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine. He is a member of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group.