How can physicians and engineers help design athletic equipment and diagnostic tools to better protect teenaged athletes from concussions? A unique group of researchers with neuroscience, bioengineering and clinical expertise are teaming up to translate preclinical research and human studies into better diagnostic tools for the clinic and the sidelines as well as creating the foundation for better headgear and other protective equipment.

The study will be led by three coinvestigators: Susan Margulies, the Robert D. Bent Professor of Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Engineering and Applied Science (right); Kristy Arbogast, co-scientific director of the Center for Injury Research and Prevention at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia; and Christina Master, a primary care sports medicine specialist and concussion researcher at CHOP. They will use a new $4.5 million award from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

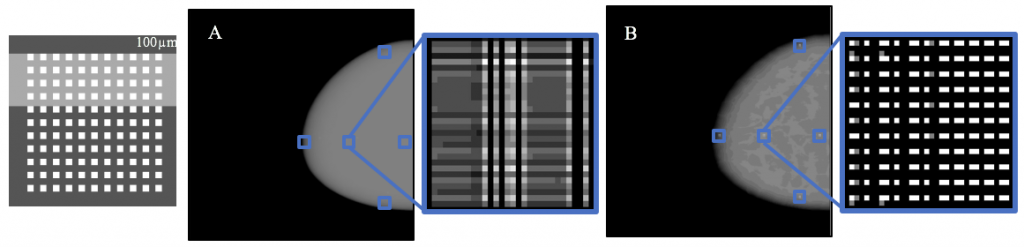

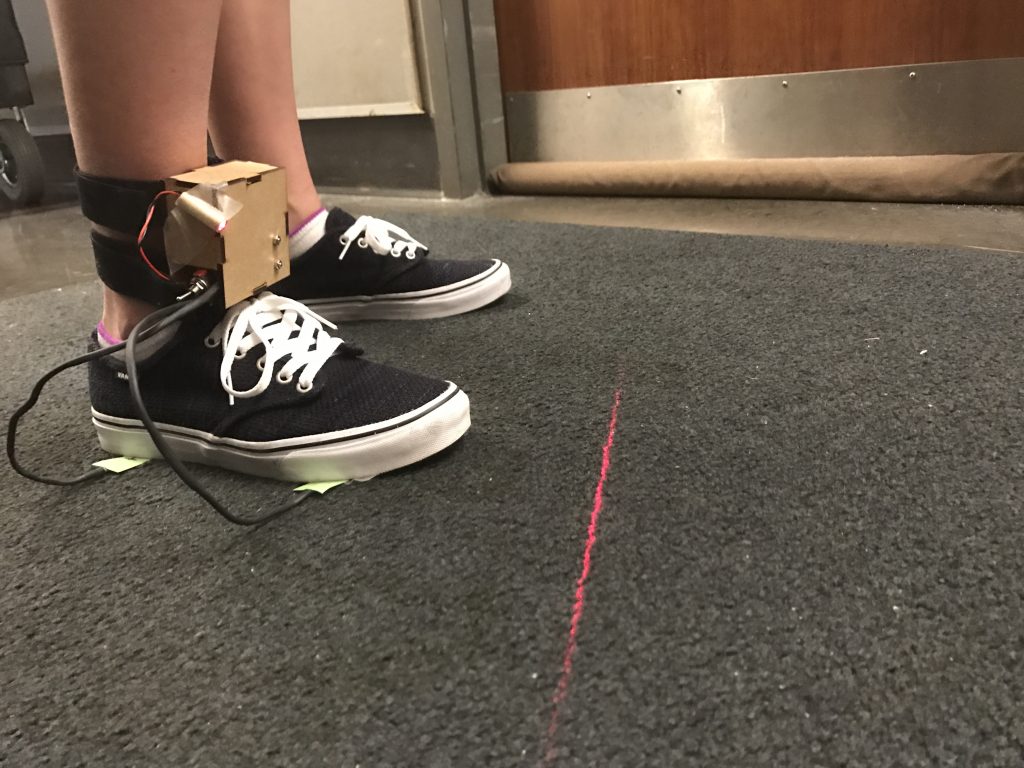

The five-year project focuses specifically on developing a suite of quantitative assessment tools to enhance accuracy of sports-related concussion diagnoses, with a focus on objective metrics of activity, balance, neurosensory processing, including eye tracking, and measures of cerebral blood flow. These could also provide prognoses of the time-to-recovery and safe return-to-play for youth athletes. Researchers will examine such factors such as repeated exposures and direction of head motion. In addition, they will also look at sex-specific data to see how prevention and diagnosis strategies need to be tailored for males and females.

The multidisciplinary research team believes this study will result in post-concussion metrics that can provide objective benchmarks for diagnosis, a preliminary understanding of the effect of sub-concussive hits, the magnitude and direction of head motion and sex on symptom time course, as well as markers in the bloodstream that relate to functional outcomes.

Knowing the biomechanical exposure and injury thresholds experienced by different player positions can help sports organizations tailor prevention strategies and companies to create protective equipment design for specific sports and even specific positions.

The study will enroll research participants from The Shipley School, a co-ed independent school in suburban Philadelphias, and from CHOP’s Concussion Care for Kids: Minds Matter program which annually sees more than 2,500 patients with concussion in the Greater Delaware Valley region.

The study is funded by the National Institutes of Health.