Genetic diseases that involve the central nervous system (CNS) often impact children before birth, meaning that once a child is born, irreversible damage has already been done. Given that many of these conditions result from a mutation in a single gene, there has been growing interest in using gene editing tools to correct these mutations before birth.

However, identifying the appropriate vehicle to deliver these gene editing tools to the CNS and brain has been a challenge. Viral vectors used to deliver gene therapies have some potential drawbacks, including pre-existing viral immunity and vector-related adverse events, and other options like lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) have not been investigated extensively in the perinatal brain.

Now, researchers in the Center for Fetal Research at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (CHOP) and Penn Engineering have identified an ionizable LNP that can deliver mRNA base editing tools to the brain and have shown it can mitigate CNS disease in perinatal mouse models. The findings, published in ACS Nano, open the door to mRNA therapies that could be delivered pre- or postnatally to treat genetic CNS diseases.

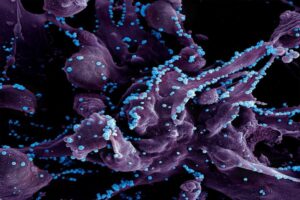

The research team began by screening a library of ionizable LNPs – microscopic fat bubbles that have a positive charge at low pH but neutral charge at physiological conditions in the body. After identifying which LNPs were best able to penetrate the blood-brain barrier in fetal and newborn mice, they optimized their top-performing LNP to be able to deliver base editing tools. The LNPs were then used to deliver mRNA for an adenine base editor, which would correct a disease-causing mutation in the lysosomal storage disease, MPSI, by changing the errant adenine to guanine.

The researchers showed that their LNP was able to improve the symptoms of the lysosomal storage disease in the neonatal mouse brain, as well as deliver mRNA base editing tools to the brain of other animal models. They also showed the LNP was stable in human cerebrospinal fluid and could deliver mRNA base editing tools to patient-derived brain tissue.

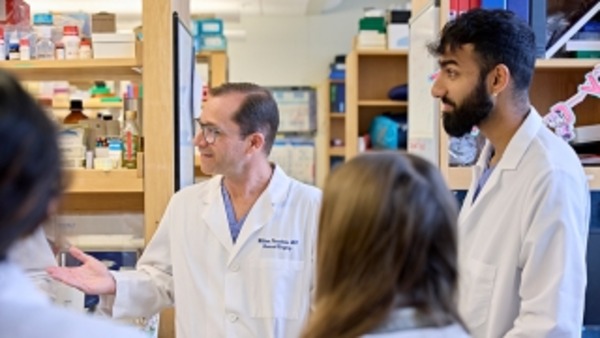

“This proof-of-concept study – co-led by Rohan Palanki, an MD/PhD student in my lab, and Michael Mitchell’s lab at Penn Bioengineering – supports the safety and efficacy of LNPs for the delivery of mRNA-based therapies to the central nervous system,” said co-senior author William H. Peranteau, MD, an attending surgeon in the Division of General, Thoracic and Fetal Surgery at CHOP and the Adzick-McCausland Distinguished Chair in Fetal and Pediatric Surgery. “Taken together, these experiments provide the foundation for additional translational studies and demonstrate base editing facilitated by a nonviral delivery carrier in the NHP fetal brain and primary human brain tissue.”

This story was written by Dana Bate. It originally appeared on CHOP’s website.

A research team led by engineers at the

A research team led by engineers at the