A message from Penn Bioengineering Professor and Chair Ravi Radhakrishnan:

In response to the unprecedented challenges presented by the global outbreak of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, Penn Bioengineering’s faculty, students, and staff are finding innovative ways of pivoting their research and academic projects to contribute to the fight against COVID-19. Though these projects are all works in progress, I think it is vitally important to keep those in our broader communities informed of the critical contributions our people are making. Whether adapting current research to focus on COVID-19, investing time, technology, and equipment to help health care infrastructure, or creating new outreach and educational programs for students, I am incredibly proud of the way Penn Bioengineering is making a difference. I invite you to read more about our ongoing projects below.

In response to the unprecedented challenges presented by the global outbreak of the novel coronavirus SARS-CoV-2, Penn Bioengineering’s faculty, students, and staff are finding innovative ways of pivoting their research and academic projects to contribute to the fight against COVID-19. Though these projects are all works in progress, I think it is vitally important to keep those in our broader communities informed of the critical contributions our people are making. Whether adapting current research to focus on COVID-19, investing time, technology, and equipment to help health care infrastructure, or creating new outreach and educational programs for students, I am incredibly proud of the way Penn Bioengineering is making a difference. I invite you to read more about our ongoing projects below.

RESEARCH

Novel Chest X-Ray Contrast

David Cormode, Associate Professor of Radiology and Bioengineering

Nanomedicine and Molecular Imaging Lab

Peter Noel, Assistant Professor of Radiology and BE Graduate Group Member

Laboratory for Advanced Computed Tomography Imaging

The Cormode and Noel labs are working to develop dark-field X-ray imaging, which may prove very helpful for COVID patients. It involves fabricating diffusers that incorporate gold nanoparticles to modify the X-ray beam. This method gives excellent images of lung structure. Chest X-ray is being used on the front lines for COVID patients, and this could potentially be an easy to implement modification of existing X-ray systems. The additional data give insight into the health state of the microstructures (alveoli) in the lung. This new contrast mechanics could be an early insight into the disease status of COVID-19 patients. For more on this research, see Cormode and Noel’s chapter in the forthcoming volume Spectral, Photon Counting Computed Tomography: Technology and Applications, edited by Katsuyuki Taguchi, Ira Blevis, and Krzysztof Iniewski (Routledge 2020).

Immunotherapy

Michael J. Mitchell, Skirkanich Assistant Professor of Innovation in Bioengineering

Mike Mitchell is working with Saar Gill (Penn Medicine) on engineering drug delivery technologies for COVID-19 mRNA vaccination. He is also developing inhalable drug delivery technologies to block COVID-19 internalization into the lungs. These new technologies are adaptations of prior research published Volume 20 of Nano Letters (“Ionizable Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated mRNA Delivery for Human CAR T Cell Engineering” January 2020) and discussed in Volume 18 of Nature Reviews Drug Discovery (“Delivery Technologies for Cancer Immunotherapy” January 2019).

Respiratory Distress Therapy Modeling

Ravi Radhakrishnan, Professor, and Chair of Bioengineering and Professor of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

Computational Models for Targeting Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS). The severe forms of COVID-19 infections resulting in death proceeds by the propagation of the acute respiratory distress syndrome or ARDS. In ARDS, the lungs fill up with fluid preventing oxygenation and effective delivery of therapeutics through the inhalation route. To overcome this major limitation, delivery of antiinflammatory drugs through the vasculature (IV injection) is a better approach; however, the high injected dose required can lead to toxicity. A group of undergraduate and postdoctoral researchers in the Radhakrishnan Lab (Emma Glass, Christina Eng, Samaneh Farokhirad, and Sreeja Kandy) are developing a computational model that can design drug-filled nanoparticles and target them to the inflamed lung regions. The model combines different length-scales, (namely, pharmacodynamic factors at the organ scale, hydrodynamic and transport factors in the tissue scale, and nanoparticle-cell interaction at the subcellular scale), into one integrated framework. This targeted approach can significantly decrease the required dose for combating ARDS. This project is done in collaboration with Clinical Scientist Dr. Jacob Brenner, who is an attending ER Physician in Penn Medicine. This research is adapted from prior findings published in Volume 13, Issue 4 of Nanomedicine: Nanotechnology, Biology and Medicine: “Mechanisms that determine nanocarrier targeting to healthy versus inflamed lung regions” (May 2017).

Diagnostics

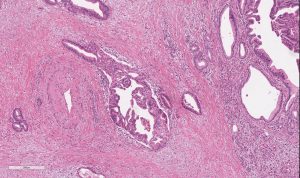

Sydney Shaffer, Assistant Professor of Bioengineering and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Arjun Raj, Professor of Bioengineering

David Issadore, Associate Professor of Bioengineering and Electrical and Systems Engineering

Arjun Raj, David Issadore, and Sydney Shaffer are working on developing an integrated, rapid point-of-care diagnostic for SARS-CoV-2 using single molecule RNA FISH. The platform currently in development uses sequence specific fluorescent probes that bind to the viral RNA when it is present. The fluorescent probes are detected using a iPhone compatible point-of-care reader device that determines whether the specimen is infected or uninfected. As the entire assay takes less than 10 minutes and can be performed with minimal equipment, we envision that this platform could ultimately be used for screening for active COVID19 at doctors’ offices and testing sites. Support for this project will come from a recently-announced IRM Collaborative Research Grant from the Institute of Regenerative Medicine with matching funding provided by the Departments of Bioengineering and Pathology and Laboratory Medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine (PSOM) (PI’s: Sydney Shaffer, Sara Cherry, Ophir Shalem, Arjun Raj). This research is adapted from findings published in the journal Lab on a Chip: “Multiplexed detection of viral infections using rapid in situ RNA analysis on a chip” (Issue 15, 2015). See also United States Provisional Patent Application Serial No. 14/900,494 (2014): “Methods for rapid ribonucleic acid fluorescence in situ hybridization” (Inventors: Raj A., Shaffer S.M., Issadore D.).

HEALTH CARE INFRASTRUCTURE

Penn Health-Tech Coronavirus COVID-19 Collaborations

Brian Litt, Professor of Bioengineering, Neurology, and Neurosurgery

In his role as one of the faculty directors for Penn Health-Tech, Professor Brian Litt is working closely with me to facilitate all the rapid response team initiatives, and in helping to garner support the center and remove obstacles. These projects include ramping up ventilator capacity and fabrication of ventilator parts, the creation of point-of-care ultrasounds and diagnostic testing, evaluating processes of PPE decontamination, and more. Visit the Penn Health-Tech coronavirus website to learn more, get involved with an existing team, or submit a new idea.

BE Labs COVID-19 Efforts

BE Educational Labs Director Sevile Mannickarottu & Staff

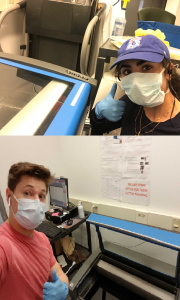

The George H. Stephenson Foundation Educational Laboratory & Bio-MakerSpace staff have donated their PPE to Penn Medicine. Two staff members (Dana Abulez, BE ’19, Master’s BE ’20 and Matthew Zwimpfer, MSE ’18, Master’s MSE ’19) took shifts to laser-cut face shields in collaboration with Penn Health-Tech. Dana and Matthew are also working with Dr. Matthew Maltese on his low-cost ventilator project (details below).

Low-Cost Ventilator

Matthew Maltese, Adjunct Professor of Medical Devices and BE Graduate Group Member

Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia Center for Injury Research and Prevention (CIRP)

Dr. Maltese is rapidly developing a low-cost ventilator that could be deployed in Penn Medicine for the expected surge, and any surge in subsequent waves. This design is currently under consideration by the FDA for Emergency Use Authorization (EUA). This example is one of several designs considered by Penn Medicine in dealing with the patient surge.

Face Shields

David F. Meaney, Solomon R. Pollack Professor of Bioengineering and Senior Associate Dean

Molecular Neuroengineering Lab

Led by David Meaney, Kevin Turner, Peter Bruno and Mark Yim, the face shield team at Penn Health-Tech is working on developing thousands of rapidly producible shields to protect and prolong the usage of Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). Learn more about Penn Health-Tech’s initiatives and apply to get involved here.

Update 4/29/20: The Penn Engineering community has sprung into action over the course of the past few weeks in response to COVID-19. Dr. Meaney shared his perspective on those efforts and the ones that will come online as the pandemic continues to unfold. Read the full post on the Penn Engineering blog.

OUTREACH & EDUCATION

Student Community Building

Yale Cohen, Professor of Otorhinolaryngology, Department of Psychology, BE Graduate Group Member, and BE Graduate Chair

Yale Cohen, and Penn Bioengineering’s Graduate Chair, is working with Penn faculty and peer institutions across the country to identify intellectually engaging and/or community-building activities for Bioengineering students. While those ideas are in progress, he has also worked with BE Department Chair Ravi Radhakrishnan and Undergraduate Chair Andrew Tsourkas to set up a dedicated Penn Bioengineering slack channel open to all Penn Bioengineering Undergrads, Master’s and Doctoral Students, and Postdocs as well as faculty and staff. It has already become an enjoyable place for the Penn BE community to connect and share ideas, articles, and funny memes.

Undergraduate Course: Biotechnology, Immunology, Vaccines and COVID-19 (ENGR 35)

Daniel A. Hammer, Alfred G. and Meta A. Ennis Professor of Bioengineering and Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering

This Summer Session II, Professor Dan Hammer and CBE Senior Lecturer Miriam R. Wattenbarger will teach a brand-new course introducing Penn undergraduates to a basic understanding of biological systems, immunology, viruses, and vaccines. This course will start with the fundamentals of biotechnology, and no prior knowledge of biotechnology is necessary. Some chemistry is needed to understand how biological systems work. The course will cover basic concepts in biotechnology, including DNA, RNA, the Central Dogma, proteins, recombinant DNA technology, polymerase chain reaction, DNA sequencing, the functioning of the immune system, acquired vs. innate immunity, viruses (including HIV, influenza, adenovirus, and coronavirus), gene therapy, CRISPR-Cas9 editing, drug discovery, types of pharmaceuticals (including small molecule inhibitors and monoclonal antibodies), vaccines, clinical trials. Some quantitative principles will be used to quantifying the strength of binding, calculate the dynamics of enzymes, writing and solving simple epidemiological models, methods for making and purifying drugs and vaccines. The course will end with specific case study of coronavirus pandemic, types of drugs proposed and their mechanism of action, and vaccine development.

Update 4/29/20: Read the Penn Engineering blog post on this course published April 27, 2020.

Neuromatch Conference

Konrad Kording, Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor of Bioengineering, Neuroscience, and Computer and Information Science

Dr. Kording facilitated Neuromatch 2020, a large virtual neurosciences conferences consisting of over 3,000 registrants. All of the conference talk videos are archived on the conference website and Dr. Kording has blogged about what he learned in the course of running a large conference entirely online. Based on the success of Neuromatch 1.0, the team are now working on planning Neuromatch 2.0, which will take place in May 2020. Dr. Kording is also working on facilitating the transition of neuroscience communication into the online space, including a weekly social (#neurodrinking) with both US and EU versions.

Neuromatch Academy

Konrad Kording, Penn Integrates Knowledge University Professor of Bioengineering, Neuroscience, and Computer and Information Science

Dr. Kording is working to launch the Neuromatch Academy, an open, online, 3-week intensive tutorial-based computational neuroscience training event (July 13-31, 2020). Participants from undergraduate to professors as well as industry are welcome. The Neuromatch Academy will introduce traditional and emerging computational neuroscience tools, their complementarity, and what they can tell us about the brain. A main focus is not just on using the techniques, but on understanding how they relate to biological questions. The school will be Python-based making use of Google Colab. The Academy will also include professional development / meta-science, model interpretation, and networking sessions. The goal is to give participants the computational background needed to do research in neuroscience. Interested participants can learn more and apply here.

Journal of Biomedical Engineering Call for Review Articles

Beth Winkelstein, Vice Provost for Education and Eduardo D. Glandt President’s Distinguished Professor of Bioengineering

The American Society of Medical Engineers’ (ASME) Journal of Biomechanical Engineering (JBME), of which Dr. Winkelstein is an Editor, has put out a call for review articles by trainees for a special issue of the journal. The call was made in March 2020 when many labs were ramping down, and trainees began refocusing on review articles and remote work. This call continues the JBME’s long history of supporting junior faculty and trainees and promoting their intellectual contributions during challenging times.

Update 4/29/20: CFP for the special 2021 issue here.

Are you a Penn Bioengineering community member involved in a coronavirus-related project? Let us know! Please reach out to ksas@seas.upenn.edu.