By Yasmina Al Ghadban, Bioengineering ’20; and Rebecca Zappala, Bioengineering ‘21

This morning, after a breakfast of eggs, sausage, and toast, we headed to the Maternal and Child Welfare Center (at the Komfo Anokye teaching hospital) to visit the malnutrition ward. We learned about two types of severe acute malnutrition: marasmus, which is characterized by severe wasting due to starvation and a lack of both protein and energy nutrients; and kwashiorkor, which is characterized by swelling of the belly, cheeks, and limbs due to a lack of protein in the diet. We also learned about the process of treatment starting from diagnosis by measuring the mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC), as well as the weight. After the specific case of malnutrition has been diagnosed, healthcare providers look for underlying conditions, such as infection, anemia, HIV, or malaria, by running lab tests. For treatment, depending on the severity of the case and the age of the child, they administer F75 or F100, which are different kinds of ready-to-use therapeutic agents. After learning about the third case that we will be working on, we went to the nutrition center where families are sent for outpatient care and follow-up. This is also the first point of contact between the family and the healthcare system; if the case is severe, the patient is referred to the malnutrition ward that we first visited. At first, we had questions about how the follow-up process works. We discovered that mothers are supposed to come back weekly to collect more food and check the weight and MUAC of their children to track their progress. In cases in which mothers do not come back for their follow-up, they are called and sometimes even visited at their homes by nurses.

Although we had visited this same ward yesterday, it is still so hard to look at the children there. The clinic seems to be doing everything they can; however, it is difficult to ignore that there is a clear lack of resources, funds, and accessibility. For example, the malnutrition center had to move from being a 2-room clinic to a 1-room clinic due to a lack of funds. This resulted in having the waiting area, the food distribution, and the assessment of the child in the same confined space, which then limits the number of patients they can care for at once.

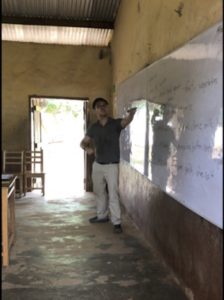

Later in the afternoon, after a drive through the market and a stop to get coconuts, we headed to Kokoben Municipal Assembly school (kindergarten through grade 9) for service. We were divided into pairs, which each taught a class about something the grade was currently working on or wanted to learn. The experiences ranged from singing with 5-year-olds and struggling to communicate in English, as most children only know Twi, to teaching about heart diseases and the circulatory system. There was a lot of shock at first since it was not easy to stand in front of 40 students and teach an unprepared lesson. Overall, the kids seemed very excited and fascinated by our presence. Although we were glad we were able to spend some time with them and share an (infinitely) small part of knowledge, we were shocked by their fascination and overwhelming joy to see us.

As on our fourth day in Ghana, we feel like we have learned so much — both about the healthcare system and the culture, and we look forward to continuing to learn and grow tomorrow.