A recent study by Penn Bioengineering researchers sheds new light on the role of physics in kidney development. The kidney uses structures called nephrons and tubules to filter blood and pass urine to the bladder. Nephron number is set at birth and can vary over an order of magnitude (anywhere from 100,000 to over a million nephrons in an individual kidney). While the reasons for this variability remain unclear, low numbers of nephrons predispose patients to hypertension and chronic kidney disease.

Now, research published in Developmental Cell led by Alex J. Hughes, Assistant Professor in the Department of Bioengineering, demonstrates a new physics-driven approach to better visualize and understand how a healthy kidney develops to avoid organizational defects that would impair its function. While previous efforts have typically approached this problem using molecular genetics and mouse models, the Hughes Lab’s physics-based approach could link particular types of defects to this genetic information and possibly highlight new treatments to prevent or fix congenital defects.

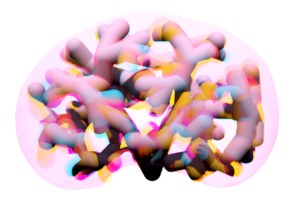

During embryonic development, kidney tubules grow and the tips divide to make a branched tree with clusters of nephron stem cells surrounding each branch tip. In order to build more nephrons, the tree needs to grow more branches. To keep the branches from overlapping, the kidney’s surface grows more crowded as the number of branches increase. “At this point, it’s like adding more people to a crowded elevator,” says Louis Prahl, first author of the paper and Postdoctoral Fellow in the Hughes Lab. “The branches need to keep rearranging to accommodate more until organ growth stops.”

To understand this process, Hughes, Prahl and their team investigated branch organization in mouse kidneys as well as using computer models and a 3D printed model of tubules. Their results show that tubules have to actively restructure – essentially divide at narrower angles – to accommodate more tubules. Computer simulations also identified ‘defective’ packing, in which the simulation parameters caused tubules to either overlap or be forced beneath the kidney surface. The team’s experimentation and analysis of published studies of genetic mouse models of kidney disease confirmed that these defects do occur.

This study represents a unique synthesis of different fields to understand congenital kidney disease. Mathematicians have studied geometric packing problems for decades in other contexts, but the structural features of the kidney present new applications for these models. Previous models of kidney branching have approached these problems from the perspective of individual branches or using purely geometric models that don’t account for tissue mechanics. By contrast, The Hughes Lab’s computer model demonstrates the physics of how tubule families interact with each other, allowing them to identify ‘phases’ of kidney organization that either relate to normal kidney development or organizational defects. Their 3D printed model of tubules shows that these effects can occur even when one sets the biology aside.

Hughes has been widely recognized for his research in the understanding of kidney development. This new publication is the first fruit of his 2021 CAREER Award from the National Science Foundation (NSF) and he was recently named a 2023 Rising Star by the Cellular and Molecular Bioengineering (CMBE) Special Interest Group. In 2020 he became the first Penn Engineering faculty member to receive the Maximizing Investigators’ Research Award (MIRA) from the National Institutes of Health (NIH) for his forward-thinking work in the creation of new tools for tissue engineering.

Pediatric nephrologists have long worked to understand the cause of these childhood kidney defects. These efforts are often confounded by a lack of evidence for a single causative mutation. The Hughes Lab’s approach presents a new and different application of the packing problem and could help answer some of these unsolved questions and open doors to prevention of these diseases. Following this study, Hughes and his lab members will continue to explore the physics of kidney tubule packing, looking for interesting connections between packing organization, mechanical stresses between neighboring tubule tips, and nephron formation while attempting to copy these principles to build stem cell derived tissues to replace damaged or diseased kidney tissue. Mechanical forces play an important role in developmental biology and there is much scope for Hughes, Prahl and their colleagues to learn about these properties in relation to the kidney.

Read “The developing murine kidney actively negotiates geometric packing conflicts to avoid defects” in Developmental Cell.

Other authors include Bioengineering Ph.D. students and Hughes Lab members John Viola and Jiageng Liu.

This work was supported by NSF CAREER 2047271, NIH MIRA R35GM133380, Predoctoral Training Program in Developmental Biology T32HD083185, and NIH F32 fellowship DK126385.