Building Muscle at the Cellular Level

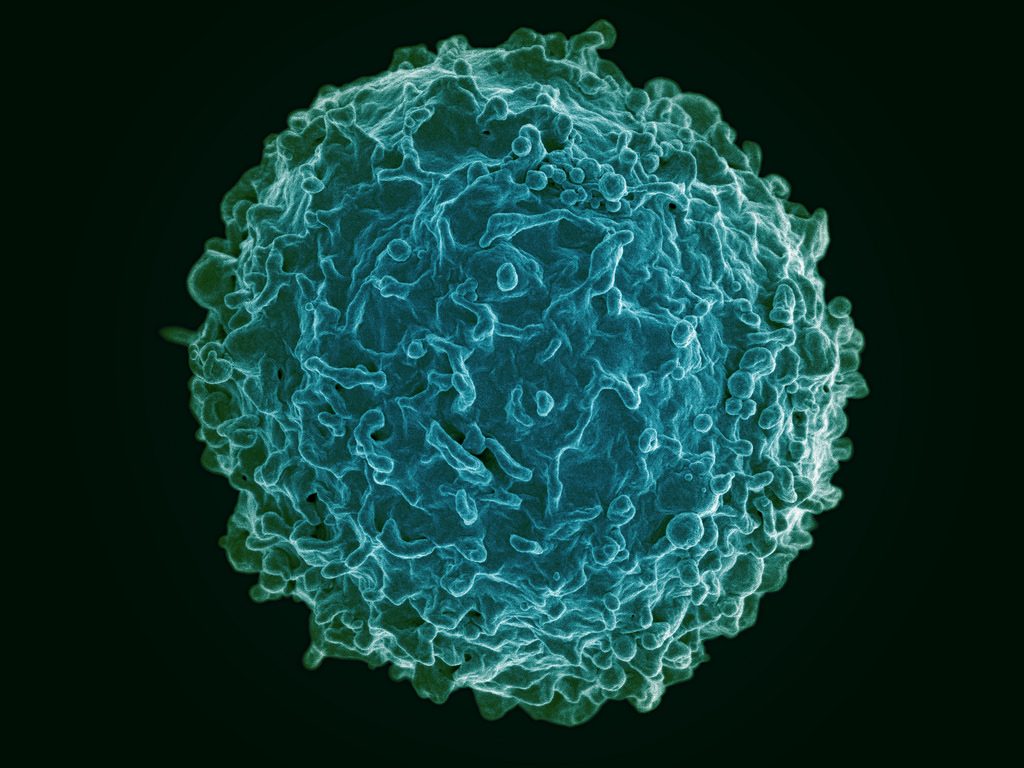

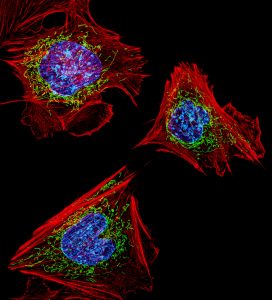

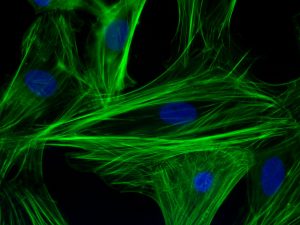

We’ve known for many years that exercise is good for you, but it was less clear how muscle strength and stamina were assembled at the molecular level. Based the principle that the health of mitochondria – a key organelle within the muscle cell – regulates muscle health, recent work identifies some of the key signaling pathways in vivo that can switch a cell between degrading damaged mitochondria or creating new mitochondria. Zhen Yan, M.D., Ph.D., of the University of Virginia, used a fluorescent reporter gene (MitoTimer) to “report back” the information for individual mitochondria in muscle cells prior to and following exercise. The results reported in a recent issue of Nature Communications show very clearly that mitochondria can switch a muscle cell’s fate. Dr. Yan’s research team identified a new signaling pathway within skeletal muscle that is essential to mitophagy. Knowledge of this pathway could help to develop a variety of therapies for diseases of the muscles or damage to the muscles due to injury.

Understanding How the Brain Processes Visual Data

As a model for how the brain “computes” the information surrounding all of us, researchers have studied how visual information is processed by the brain. One method for investigating this question is the use of artificial neural networks to recognize visual information that they have previously “seen.” A recent article in Cerebral Cortex details how a team at Purdue University, led by Zhongming Liu, Ph.D., Assistant Professor of Electrical and Computer Engineering and Biomedical Engineering, used an artificial neural network to predict and decode information obtained with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). By collecting fMRI brain activation data when people watch movies, the artificial neural network could generate feature maps that strongly resembled the objects depicted by the initial stimuli. Available now in open access format, the team at Purdue intends to repeat these experiments with more complex networks and more detailed imaging modalities

Preventing Prosthesis-related Infection

Prostheses have improved by leaps and bounds over the years, with the development of osseointegrated prostheses — which are fused directly to the existing bones — a major step in this evolution. However, these prostheses can lead to severe infections that would require the removal of the prosthesis. These problems have been seen more commonly over the last decade or so in the military, where wounded soldiers have received prostheses but suffered subsequent infections.

In a major step forward to address this issue, Mark Ehrensberger, PhD, assistant professor of biomedical engineering at SUNY Buffalo, is the principal investigator on a two-year $1.1 million grant from the Office of Naval Research in the U.S. Department of Defense, awarded for the purpose of investigating implant-related infections. Initial research by Dr. Ehrensberger, who shares the grant award with scientists from the departments of orthopaedics and microbiology and immunology, showed that delivering electrical stimulation to the site of the prosthesis could be effective. One method the team will investigate is using titanium from within the implants themselves to conduct the current to the site.

Success with this grant could mean that patients receiving prostheses show better recovery rates and much lower rates of rejection. It could also reduce the antibiotics used by such patients, which would be a welcome outcome given the increasing rates of antibiotic resistance in health care.

Bioengineering Treatments for Depression

Depression is a largely invisible illness, but it brings with it a massive burden on both the patient and society, with health care costs exceeding $200 billion per year in the U.S. alone. Different drugs are used to treat depression, but all have significant side effects. Psychotherapy also has some effectiveness, but not all patients are helped with therapy.

One promising alternative to treat depression uses transcranial magnetic stimulation, but the devices used in this treatment are often cumbersome. In response to calls to develop more accessible forms of therapy for depression, a startup company in Sweden called Flow Neuroscience has developed a wearable device that uses transcranial direct-current stimulation targeted at the left frontal lobe. The device is noninvasive and is smaller than a sun visor, and the company claims it will be relatively inexpensive (estimated at $750). Flow Neuroscience is in the process of applying for regulatory approval in the European Union.

People and Places

United Kingdom Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond has announced that the British government will provide £7 million (approximately $9.2 million) in funding to create the UK Centre for Engineering Biology, Metrology and Standards. The government is collaborating with the the Francis Crick Institute in London, with the goal of supporting startup companies in Great Britain dedicated to using engineering and the biological sciences to develop new products.

Closer to home, the Universities of Shady Grove — a partnership of nine Maryland public universities where each university provides its most heavily demanded program — have begun construction on a $162 million biomedical sciences building. The building is slated for completion in 2019 and is expected to nearly double the enrollment at Shady Grove.

Here at Penn, Adam Pardes, a current Ph.D. candidate in our own Department of Engineering, is one of the cofounders of NeuroFlow, a company developing a mobile platform to track and record biometric information obtained from wearables. NeuroFlow recently received $1.25 million in investments to continue developing its technology and ultimately bring it to market. Congratulations, Adam!

Finally, California State University, Long Beach, is our newest national BME program this fall. Burkhard Englert, Ph.D., professor and chair of the Department of Computer Engineering and Computer Science at CSULB, heads the new program as interim chair until a permanent chair is hired.

Jason Burdick, Ph.D., who is a professor in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Bioengineering, has been named one of the three chairs of the 2019 annual meeting of the

Jason Burdick, Ph.D., who is a professor in the University of Pennsylvania’s Department of Bioengineering, has been named one of the three chairs of the 2019 annual meeting of the

Biomechanics is a subdiscipline within bioengineering with many applications that include studying how tissue forms and grows during development (

Biomechanics is a subdiscipline within bioengineering with many applications that include studying how tissue forms and grows during development (