by Danielle Tsougarakis, Bioengineering ’20; Jason Grosz, Bioengineering ’19; Ethan Zhao, Bioengineering ’19; and Kate Panzer, Bioengineering ’18

David Issadore, a faculty member in the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania teaches an engineering course ENGR566 – Appropriate Point of Care Diagnostics. As part of this course, he and Miriam Wattenberger from CBE, have taken nine Penn students, most of them majoring in Bioengineering, to Kumasi, Ghana, to study the diagnosis of pediatric tuberculosis. While in Ghana, these students are blogging daily on their experiences.

The first thing we did today was visit the Komfo Anokye sword, which is a sword buried in the ground that represents the power and stability of the Ashante Kingdom. Rumor has it that, if the sword is removed from the ground, the Ashante Kingdom will collapse. To this date, no one has been able to remove the sword from the ground, and it is a tourist site frequented by famous visitors, including Muhammad Ali.

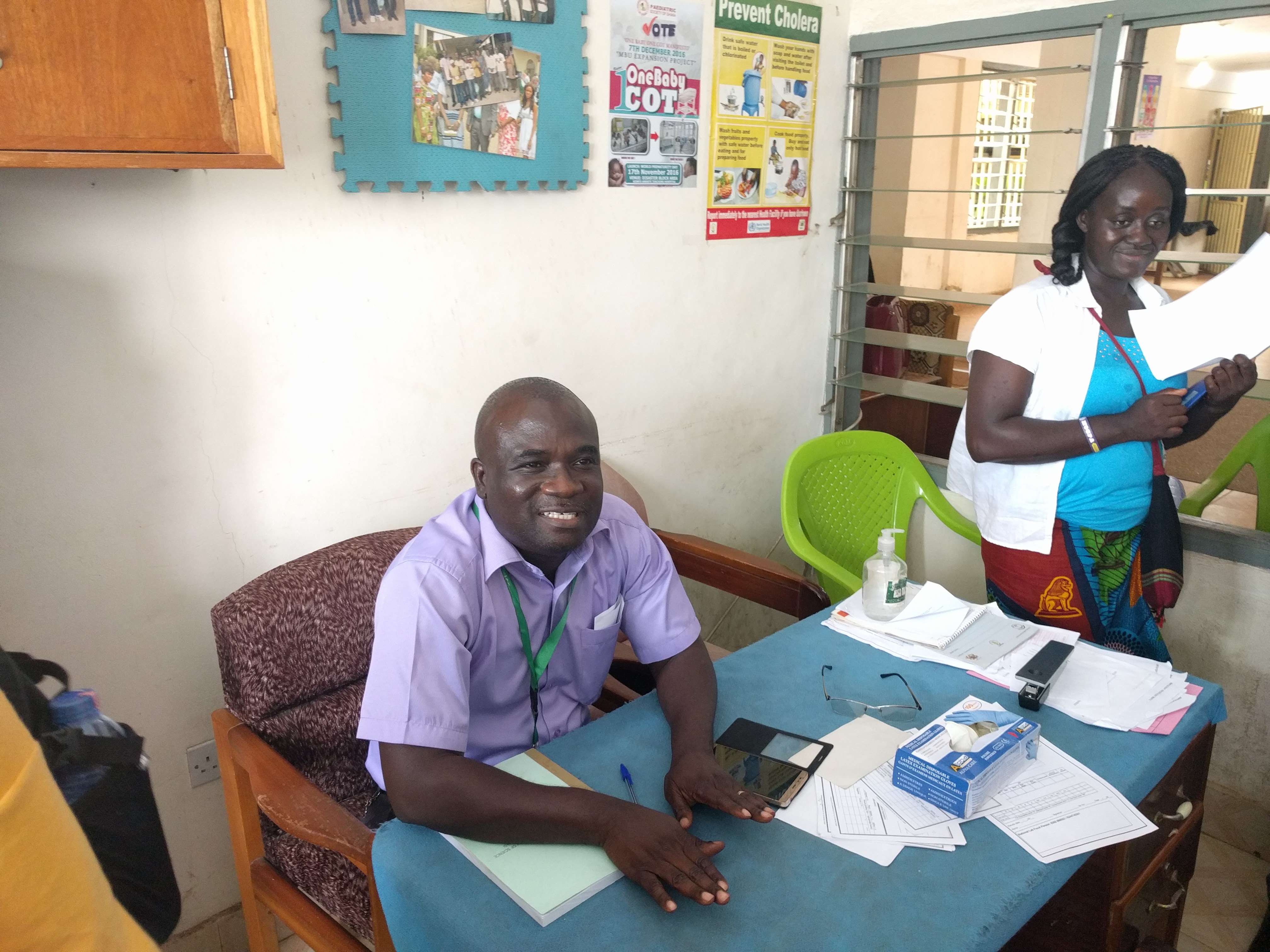

After seeing the Komfo Anokye sword, we visited a pediatric tuberculosis clinic at Komfo Anokye Teaching Hospital (KATH), the major hospital in Kumasi, which is well equipped with medical infrastructure. Upon entering the clinic, we were immediately struck by the appearance of the waiting area and check-up room. The check-up room was small and consisted of a wooden desk and plastic chairs. The windows and doors remained open to the outside and waiting area such that any passers-by could listen to the check-up. The clinic was not very busy while we were there, but the doctor said that that was atypical; typically, he is completely booked and has to rush from appointment to appointment.

The first patient was a five-year-old child who was referred from another doctor for persistent coughing, weight loss, fever, and vomiting. These are all classic symptoms of tuberculosis, so the doctor ordered a smear microscopy diagnostic on the patient’s sputum and a digital X-ray. If the sputum sample is viable, it will also be sent for molecular diagnostics with the GeneXpert. One thing that we found surprising was that the cost to the patient for the diagnostics and the check-up was $0 — it is all funded by the government and NGOs.

The second patient was also a five-year-old child currently being treated with anti-tuberculosis medication and anti-retroviral therapy for HIV. His symptoms included wheezing, coughing, and an extremely rapid heartbeat. Given the patient’s history of HIV, the doctor suspected acute pneumonia and/or drug-resistant tuberculosis and admitted him to the emergency room for observation and treatment. One thing that we found surprising was that infant patients in the emergency room usually share beds with up to seven other infant patients. This makes hospital-borne infections extremely common and dangerous. We also found it interesting that only the mother was allowed to accompany the child to the emergency room, but the father was given the final say for all important medical decisions.

After the clinic visit, we went to a nearby rural high school, where we planned to tutor the students in science and math. Upon arrival, we were told which subject we would be teaching just before we were essentially thrown into the classrooms without much preparation. This tutoring session was held after the usual class period, but the students were eager to stay, learn, and interact with us. The school was split into two forms similar to the British school system, with the underclassmen in Form 1 and the upperclassmen in Form 2.

The high school has about 900 students, split into eight classrooms with sides that open to the warm Ghanaian air. The rooms hold classes of varying sizes from 25 to 50 students, with ages between 13 and 18 years. Some of the subjects taught in the different classrooms include physiology (the cardiovascular system), math (algebraic expressions, change of subject, quadratic equations, etc.), and language arts (article and essay writing). Each room was filled with goofy, lively students who would occasionally break out in giggles and applause to encourage their classmates who volunteered to come to the board.

We all had a blast interacting with the students, attempting different teaching techniques on the spot and brainstorming ways to get the students excited about the class topics. Despite the initial nerves of not knowing what we would be teaching until just before entering the classrooms, we look back at this experience with excitement, and we are looking forward to returning to the classrooms to tutor on Friday.