“We need to think big in antibiotics research,” says Cesar de la Fuente. “Over one million people die every year from drug-resistant infections, and this is predicted to reach 10 million by 2050. There hasn’t been a truly new class of antibiotics in decades, and there are so few of us tackling this issue that we need to be thinking about more than just new drugs. We need new frameworks.”

De la Fuente is Presidential Assistant Professor in the Department of Bioengineering and the Department of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering at the University of Pennsylvania School of Engineering and Applied Science. He holds additional primary appointments in Psychiatry and Microbiology in the Perelman School of Medicine.

De la Fuente’s lab, the Machine Biology Group, creates these new frameworks using potent partnerships in engineering and the health sciences, drawing on the “power of machines to accelerate discoveries in biology and medicine.”

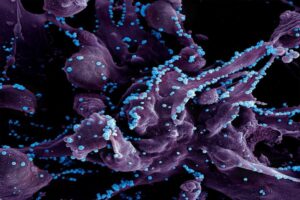

Marrying artificial intelligence with advanced experimental methods, the group has mined the ancient past for future medical breakthroughs. In a recent study published in Cell Host and Microbe, the team has launched the field of “molecular de-extinction.”

Our genomes – our genetic material – and the genomes of our ancient ancestors, express proteins with natural antimicrobial properties. “Molecular de-extinction” hypothesizes that these molecules could be prime candidates for safe new drugs. Naturally produced and selected through evolution, these molecules offer promising advantages over molecular discovery using AI alone.

In this paper, the team explored the proteomic expressions of two extinct organisms –Neanderthals and Denisovans, archaic precursors to the human species – and found dozens of small protein sequences with antibiotic qualities. Their lab then worked to synthesize these molecules, bringing these long-since-vanished chemistries back to life.

“The computer gives us a sequence of amino acids,” says de la Fuente. “These are the building blocks of a peptide, a small protein. Then we can make these molecules using a method called ‘solid-phase chemical synthesis.’ We translate the recipe of amino acids into an actual molecule and then build it.”

The team next applied these molecules to pathogens in a dish and in mice to test the veracity and efficacy of their computational predictions.

“The ones that worked, worked quite well,” continues de la Fuente. “In two cases, the peptides were comparable – if not better – than the standard of care. The ones that didn’t work helped us learn what needed to be improved in our AI tools. We think this research opens the door to new ways of thinking about antibiotics and drug discovery, and this first step will allow scientists to explore it with increasing creativity and precision.”

Read the full story in Penn Engineering Today.

Cosette Tomita, a master’s student in Bioengineering, spoke with Penn Engineering Graduate Admissions about her research in cellular therapy and her path to Penn Engineering.

Cosette Tomita, a master’s student in Bioengineering, spoke with Penn Engineering Graduate Admissions about her research in cellular therapy and her path to Penn Engineering.

Carlos Armando Aguila, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center of Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, advised by

Carlos Armando Aguila, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center of Neuroengineering and Therapeutics, advised by  Joseph Lance Victoria Casila is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of

Joseph Lance Victoria Casila is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of  Trevor Chan is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of

Trevor Chan is a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering in the lab of  Rakan El-Mayta is an incoming Ph.D. student in the lab of

Rakan El-Mayta is an incoming Ph.D. student in the lab of  Austin Jenk is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Austin Jenk is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Jiageng Liu is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Jiageng Liu is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Alexandra Neeser is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Alexandra Neeser is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  William Karl Selboe Ojemann, a Ph.D. Student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics directed by

William Karl Selboe Ojemann, a Ph.D. Student in Bioengineering, is a member of the Center for Neuroengineering and Therapeutics directed by  Savan Patel (BSE Class of 2023) conducted research in the lab of

Savan Patel (BSE Class of 2023) conducted research in the lab of  David E. Reynolds, a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of

David E. Reynolds, a Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of  Andre Roots is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Andre Roots is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Emily Sharp, a second year Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of

Emily Sharp, a second year Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member of the lab of  Nat Thurlow is a Ph.D. student in the lab of

Nat Thurlow is a Ph.D. student in the lab of  Maggie Wagner, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member in the labs of

Maggie Wagner, Ph.D. student in Bioengineering, is a member in the labs of