by Rachel Ewing

Vaccines for COVID-19 were the first time that mRNA technology was used to address a worldwide health challenge. The Penn Medicine scientists behind that technology were awarded the 2023 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Next come all the rest of the potential new treatments made possible by their discoveries.

Starting in the late 1990s, working together at Penn Medicine, Katalin Karikó, PhD, and Drew Weissman, MD, PhD, discovered how to safely use messenger RNA (mRNA) as a whole new type of vaccine or therapy for diseases. When the COVID-19 pandemic hit in 2020, these discoveries made Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna’s new vaccines possible—saving millions of lives.

But curbing the pandemic was only the beginning of the potential for this Nobel Prize-winning technology.

These biomedical innovations from Penn Medicine in using mRNA represent a multi-use tool, not just a treatment for a single disease. The technology’s potential is virtually unlimited; if researchers know the sequence of a particular protein they want to create or replace, it should be possible to target a specific disease. Through the Penn Institute for RNA Innovation led by Weissman, who is the Roberts Family Professor of Vaccine Research in Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, researchers are working to ensure this limitless potential meets the world’s most challenging and important needs.

Infectious Diseases and Beyond

Just consider some of the many projects Weissman’s lab is partnering in: “We’re working on malaria with people across the U.S. and in Africa,” Weissman said. “We’re working on leptospirosis with people in Southeast Asia. We’re working on vaccines for peanut allergies. We’re working on vaccines for autoimmunity. And all of this is through collaboration.”

Clinical trials are underway for the new malaria vaccine, as well as for a Penn-developed mRNA vaccine for genital herpes and one that aims to protect against all varieties of coronaviruses. Trials should begin soon for vaccines for norovirus and the bacterium C. difficile.

Single-Injection Gene Therapies for Sickle Cell and Heart Disease

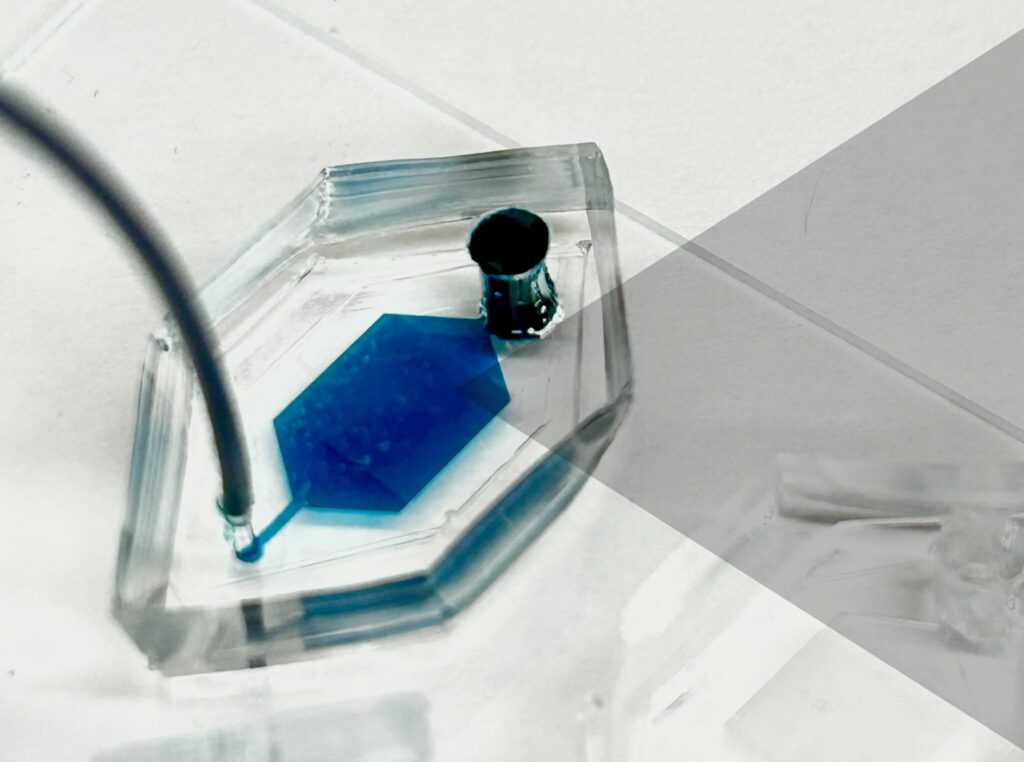

The Weissman lab is working to deploy mRNA technology as an accessible gene therapy for sickle cell anemia, a devastating and painful genetic disease that affects about 20 million people around the world. About 300,000 babies are born each year with the condition, mainly in sub-Saharan Africa. Weissman’s team has developed technology to efficiently deliver modified mRNA to bone marrow stem cells, instructing red blood cells to produce normal hemoglobin instead of the malformed “sickle” version that causes the illness. Conventional gene therapies are complex and expensive treatments, but the mRNA gene therapy could be a simple, one-time intravenous injection to cure the disease. Such a treatment would have applications to many other congenital gene defects in blood and stem cells.

In another new program, Penn Medicine researchers have found a way to target the muscle cells of the heart. This gene therapy method developed by Weissman’s team, together with Vlad Muzykantov, MD, PhD, the Founders Professor in Nanoparticle Research could potentially repair the heart or increase blood flow to the heart, noninvasively, after a heart attack or to correct a genetic deficiency in the heart. “That is important because heart disease is the number one killer in the U.S. and in the world,” Weissman said. “Drugs for heart disease aren’t specific for the heart. And when you’re trying to treat a myocardial infarction or cardiomyopathy or other genetic deficiencies in the heart, it’s very difficult, because you can’t deliver to the heart.”

Weissman’s team also is partnering on programs for neurodevelopmental diseases and for neurodegenerative diseases, to replace genes or deliver therapeutic proteins that will treat and potentially cure these diseases.

“The potential is unbelievable,” Weissman said. “We haven’t thought of everything that can be done.”

Read the full story in Penn Medicine News.

Vladimir R. Muzykantov is Founders Professor in Nanoparticle Research in the Department of Systems Pharmacology and Translational Therapeutics in the Perelman School of Medicine. He is a member of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group.