by Sophie Burkholder

University of Washington Researchers Engineer a New Way to Study Circulatory Obstruction

Capillaries are one of the most important forms of vasculature in our body, as they allow our blood to transfer nutrients to other parts of our body. But for how much effect capillary functionality can have on our health, their small size makes them extremely difficult to engineer into models for a variety of diseases. Now, researchers at the University of Washington led by Ying Zheng, Ph. D., engineered a three-dimensional microvessel model with living cells to study the mechanisms of microcirculatory obstruction involved with malaria.

Capillaries are one of the most important forms of vasculature in our body, as they allow our blood to transfer nutrients to other parts of our body. But for how much effect capillary functionality can have on our health, their small size makes them extremely difficult to engineer into models for a variety of diseases. Now, researchers at the University of Washington led by Ying Zheng, Ph. D., engineered a three-dimensional microvessel model with living cells to study the mechanisms of microcirculatory obstruction involved with malaria.

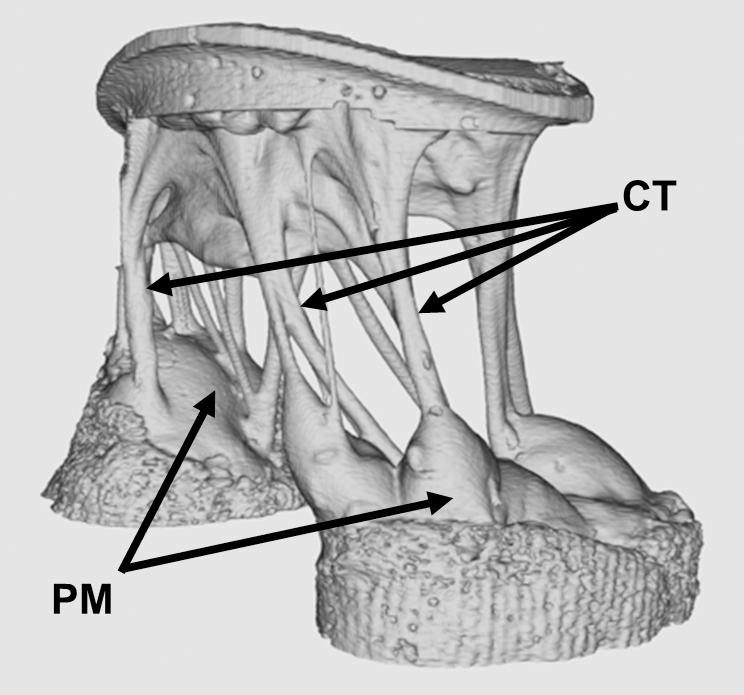

Rather than just achieving a physical model of capillaries, these researchers created a model that allowed them to study typical flow and motion through capillaries, before comparing it to deficiencies in this behavior involved with diseases like malaria. The shape of the engineered model is similar to that of an hourglass, allowing the researchers to study instances where red blood cell transit may encounter bottlenecks between the capillaries and other vessels. Using multiphoton technology, Zheng and her team created 100mm capillary models with etched-in channels and a collagen base, to closely model the typical size and rigidity of the vessels. Tested with malaria-infected blood cells, the model showed similar circulatory obstructive behavior to that which occurs in patients, giving hope that this model can be transferred to other diseases involving such obstruction, like sickle cell anemia, diabetes, and cardiovascular conditions.

Understanding a Cell Membrane Protein Could Be the Key to New Cancer Treatments

Almost every cell in the body has integrins, a form of proteins, on its membrane, allowing cells to sense biological information from beyond their membranes while also using this feedback information to initiate signals within cells themselves. Bioengineers at the Imperial College of London recently looked at the way another membrane protein, called syndecan-4, interacts with integrins as a potential form of future cancer treatment. Referred to as “cellular hands” by lead researcher of the study Armando del Rio Hernandez, Ph.D., syndecan-4 sometimes controls the development of diseases or conditions like cancer and fibrosis. Hernandez and his team specifically studied the ties of syndecan-4 to yes-associated protein (YAP) and enzyme called P13K, both of which are affiliated with qualities of cancer progression like halted apoptosis or cell stiffening. Knowing this, Hernandez and his team hope to continue research into understanding the mechanisms of syndecan-4 throughout the cell, in search of new mechanisms and targets to focus on with future developments of cancer treatments.

A New Medical Device Could Improve Nerve Functionality After Severe Damage

Serious nerve damage remains difficult to repair surgically, often involving the stretching of nerves for localized damage, or the transfer of healthy nerve cells from another part of the body to fill larger gaps in nerve damage. But these imperfect solutions limit the return of full nerve function and movement to the damaged part of the body, and in more serious cases with large areas of nerve damage, can also risk damage in other areas of the body that healthy nerves are borrowed from for treatment. A new study from the University of Pittsburgh published in Science Translational Medicine led by Kacey Marra, Ph. D., has successfully repaired nerve damage in mice and monkeys using a biodegradable tube that releases growth factors called glial-cell-derived neurotrophic factors over time.

Marra and her team showed that this new device restored nerve function up to 80% in nonhuman primates, where current methods of nerve replacement often only achieve 50-60% functionality restoration. The device might have an easier time getting FDA-approval, since it doesn’t involve the use of stem cells in its repair mechanisms. Hoping to start human clinical trials in 2021, Marra and her team hope that the device will help both injured veterans and typical patients with nerve damage, and see potential future applications in facial nerve damage as well.

A New Computational Model Could Improve Treatments for Cancer, HIV, and Autoimmune Diseases

With cancer, HIV, and other autoimmune diseases, the best treatment options for patients are often determined with trial-and-error methods, leading to prolonged instances of ineffective approaches and sometimes unnecessary side effects. A group of researchers led by Wesley Errington, Ph.D., at the University of Minnesota decided to take a computational approach this problem, in an effort to more quickly and efficiently determine the most appropriate treatment for a given patient. Based on parameters controlling interactions between molecules with multiple binding sites, the team’s new model looks primarily at binding strength, linkage rigidity, and size of linkage arrays. Because diseases can often involve issues in molecular binding, the model aimed to model the 78 unique binding configurations for cases of when interacting molecules only have three binding sites, which are often difficult to observe experimentally. This new approach will allow for faster and easier determination of treatments for patients with diseases involving these molecular interactions.

Improved Drug Screening for Glioblastoma Patients

A new microfluidic brain chip from researchers at the University of Houston could help improve treatment evaluations for brain tumors. Glioblastoma patients, who have a five-year survival rate of a little over 5%, are some of the most common patients suffering from malignant brain tumors. This new chip, developed by the lab of Yasemin Akay, Ph.D., can quickly determine cancer drug effectiveness by analyzing a piece of cultured tumor biopsy from a patient by incorporating different chemotherapy treatments through the microfluidic vessels. Overall, Akay and her team found that this new chip holds hope as a future efficient and inexpensive form of drug screening for glioblastoma patients.

People and Places

The brain constructs maps to guide people, not just of physical spaces but also to connect stimuli around them, like conversations and other people. It’s long been known that the brain area responsible for this spatial navigation—the medial temporal lobe—is also involved in recalling memories.

Now, neuroscientists at the University of Pennsylvania have discovered that the signals the brain produces during spatial navigation and episodic memory recall look similar. Low-frequency brain waves called the theta rhythm appear as people jump from one memory to the next, as many prior studies looking only at human navigation have shown. The new findings, which suggest that the brain structures responsible for helping people navigate the world may also “navigate” a mental map of prior experiences, appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Read the rest of this story featuring Penn Bioengineering’s Graduate Group member Michael Kahana and M.D./Ph.D. student Ethan Solomon on Penn Today.

The Florida Institute of Technology recently announced plans to start construction in spring 2020 on a new Health Sciences Research Center, set to further establish biomedical engineering and pre-medical coursework and research at the institute. With plans to open the new center in 2022, Florida Tech anticipates increased enrollment in the two programs, and hopes that the center will offer more opportunities in a growing professional field.

Anson Ong, Ph.D., the Associate Dean of Administration and Graduate Programs at the University of Texas at San Antonio, was recently elected to the International College of Fellows of Biomaterials Science and Engineering. With a focus on research in biomaterial implants for orthopaedic applications, Ong’s election to the college honors his advancement and contribution to the field of biomaterials research.