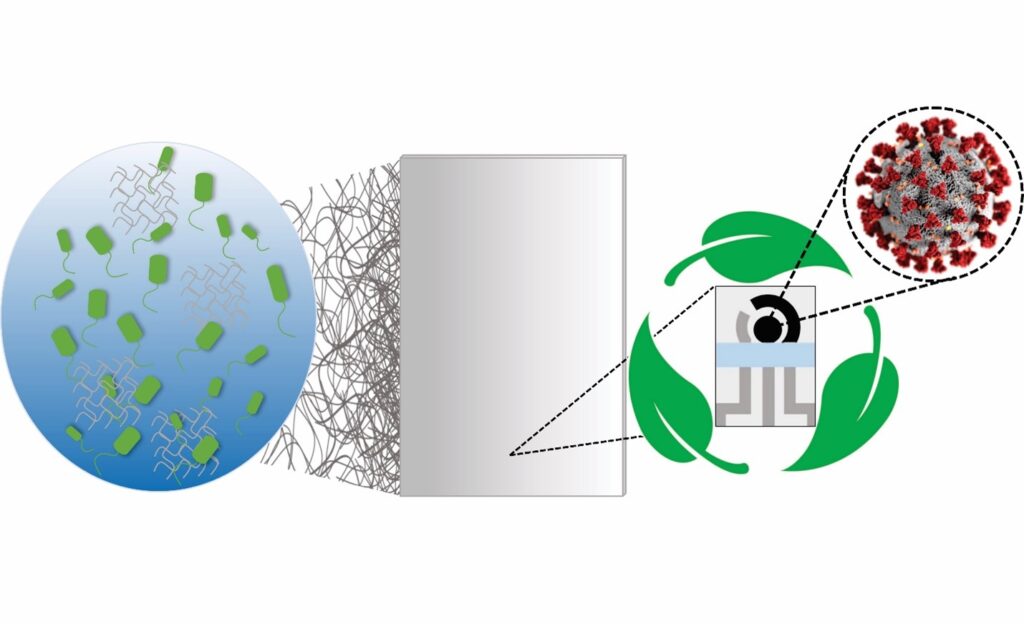

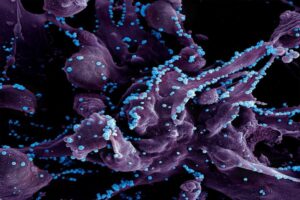

Biofilms—structured communities of microorganisms that create a protective matrix shielding them from external threats, including antibiotics—are responsible for about 80% of human infections and present a significant challenge in medical treatments, often resisting conventional methods.

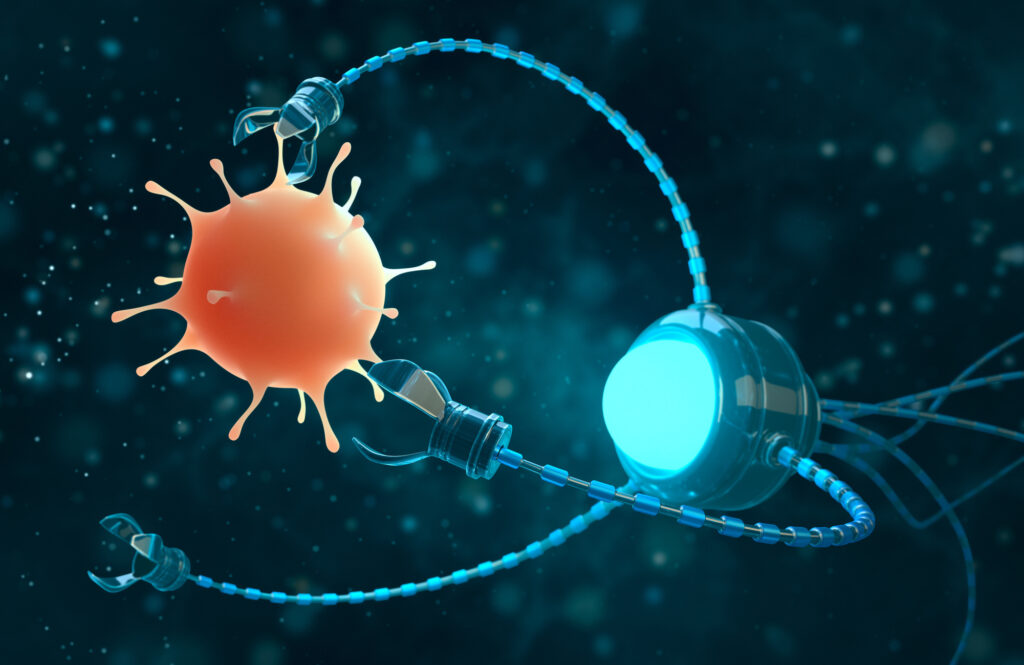

In a Q&A with Penn Today, Hyun (Michel) Koo of the School of Dental Medicine and Edward Steager of the School of Engineering and Applied Science at Penn discuss an innovative approach they’ve partnered on: the use of small-scale robotics, microrobots, to offer a promising solution to tackle these persistent infections, bringing new capabilities and precision to the field of biomedical engineering.

Q: What is the motivation behind opting for tiny robots to tackle infections?

Koo: Treating biofilms is a broad yet unresolved biomedical problem, and conversely, the strategies for tackling biofilms are limited for a number of reasons. For instance, biofilms typically occur on surfaces that can be tricky to reach, like between the teeth in the oral cavity, the respiratory tract, or even within catheters and implants, so treatments for these are usually restricted to antibiotics (or antimicrobials) and other physical methods reliant on mechanical disruption. However, this touches on the problem of antimicrobial resistance: targeting specific microorganisms present in these structures is difficult, so antibiotics often fail to reach and penetrate the biofilm’s protective layers, leading to persistent infections and increased risk of antibiotic resistance.

We needed a way to circumvent these constraints, so Ed and I teamed up in 2017 to develop new, more precise and effective approaches that leverage the engineers’ ability to generate solutions that we, the clinicians and life science researchers, identify.

Read the full interview in Penn Today.

Hyun (Michel) Koo is a professor in the Department of Orthodontics and in the divisions of Pediatric Dentistry and Community Oral Health and the co-founder of the Center for Innovation & Precision Dentistry in the School of Dental Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He is a member of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group.

Edward Steager is a senior research investigator in Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science.

Speaker:

Speaker: