by

Infections caused by fungi, such as Candida albicans, pose a significant global health risk due to their resistance to existing treatments, so much so that the World Health Organization has highlighted this as a priority issue.

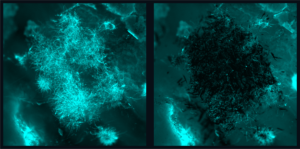

Although nanomaterials show promise as antifungal agents, current iterations lack the potency and specificity needed for quick and targeted treatment, leading to prolonged treatment times and potential off-target effects and drug resistance.

Now, in a groundbreaking development with far-reaching implications for global health, a team of researchers jointly led by Hyun (Michel) Koo of the University of Pennsylvania School of Dental Medicine and Edward Steager of Penn’s School of Engineering and Applied Science has created a microrobotic system capable of rapid, targeted elimination of fungal pathogens.

“Candida forms tenacious biofilm infections that are particularly hard to treat,” Koo says. “Current antifungal therapies lack the potency and specificity required to quickly and effectively eliminate these pathogens, so this collaboration draws from our clinical knowledge and combines Ed’s team and their robotic expertise to offer a new approach.”

The team of researchers is a part of Penn Dental’s Center for Innovation & Precision Dentistry, an initiative that leverages engineering and computational approaches to uncover new knowledge for disease mitigation and advance oral and craniofacial health care innovation.

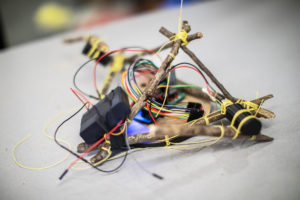

For this paper, published in Advanced Materials, the researchers capitalized on recent advancements in catalytic nanoparticles, known as nanozymes, and they built miniature robotic systems that could accurately target and quickly destroy fungal cells. They achieved this by using electromagnetic fields to control the shape and movements of these nanozyme microrobots with great precision.

“The methods we use to control the nanoparticles in this study are magnetic, which allows us to direct them to the exact infection location,” Steager says. “We use iron oxide nanoparticles, which have another important property, namely that they’re catalytic.”

Read the full story in Penn Today.

Hyun (Michel) Koo is a professor in the Department of Orthodontics and in the divisions of Pediatric Dentistry and Community Oral Health and is the co-founder of the Center for Innovation & Precision Dentistry in the School of Dental Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He is a member of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group.

Edward Steager is a research investigator in the School of Engineering and Applied Science’s General Robotics, Automation, Sensing & Perception Laboratory at Penn.

Other authors include Min Jun Oh, Alaa Babeer, Yuan Liu, Zhi Ren, Zhenting Xiang, Yilan Miao, and Chider Chen of Penn Dental; and David P. Cormode and Seokyoung Yoon of the Perelman School of Medicine. Cormode also holds a secondary appointment in Bioengineering.

This research was supported in part by the National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research (R01 DE025848, R56 DE029985, R90DE031532 and; the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea of the Ministry of Education (NRF-2021R1A6A3A03044553).