On April 17, 2024, the Department of Bioengineering held its annual Bioengineering (BE) Senior Design Presentations in the Singh Center for Nanotechnology, followed by a Design Expo in the George H. Stephenson Foundation Educational Laboratory & Bio-MakerSpace.

A panel of expert and alumni judges chose 3 teams to advance to the School-wide, interdepartmental competition, to be held on May 3, 2024.

ADONA (A Device for the Assisted Detection of Neonatal Asphyxia)

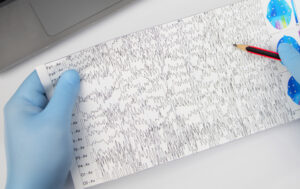

Hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) is a condition that arises from inadequate oxygen delivery or blood flow to the brain around the time of birth, resulting in long-term neurological damage. This birth complication is responsible for up to 23% of neonatal deaths worldwide. While effective treatments exist, current diagnostic methods require specialized neurologists to analyze an infant’s electroencephalography (EEG) signal, requiring significant time and labor. In areas where such resources and specialized training are even scarcer, the challenges are even more pronounced, leading to delayed or lack of treatment, and poorer patient outcomes. The Assisted Detection of Neonatal Asphyxia (ADONA) device is a non-invasive screening tool that streamlines the detection of HIE. ADONA is an EEG helmet that collects, wirelessly transmits, and automatically classifies EEG data using a proprietary machine learning algorithm in under two minutes. Our device is low-cost, automated, user-friendly, and maintains the accuracy and reliability of a trained neurologist. Our classification algorithm was trained using 1100 hours of annotated clinical data and achieved >85% specificity and >90% sensitivity on an independent 200 hour dataset. Our device is now produced in Agilus 30, a flexible and tear resistant material, that reduces form factor and ensures regulatory compliance. For our final prototype, we hope to improve electrode contact and integrate software with clinical requirements. Our hope is that ADONA will turn the promise of a safer birth into a reality, ensuring instant peace of mind and equitable access to healthcare, for every child and their families.

Epilog

To address the critical need for effective, at-home seizure monitoring in pediatric neurology, particularly for Status Epilepticus (SE), our team developed Epilog: a rapid-application electroencephalography (EEG) headband. SE is a medical emergency characterized by prolonged or successive seizures and often presents with symptoms too subtle to notice or easily misinterpreted as post-convulsive fatigue. This leads to delayed treatment and increased risks of neurological damage and high mortality. Current seizure detection technologies are primarily based on motion or full-head EEG, rendering them ineffective at detecting SE and impractical for at-home use in emergency scenarios, respectively. Our device is designed to be applied rapidly during the comedown of a convulsive seizure, collect EEG data, and feed it into our custom machine learning algorithm. The algorithm processes this data in real-time and alerts caregivers if the child remains in SE, thereby facilitating immediate medical decision-making. Currently, Epilog maintains a specificity of 0.88 and sensitivity of 0.95, delivering decisions within 15 seconds post-seizure. We have demonstrated clean EEG signal acquisition from eight standard electrode placements and bluetooth data transmission from eight channels with minimal delay. Our headband incorporates all necessary electrodes and adjustable positioning of the electrodes for different head sizes. Our unique gel case facilitates rapid electrode gelation in less than 10 seconds. Our most immediate goals are validating our fully integrated device and improving features that allow for robust, long-term use of Epilog. Epilog promises not just data, but peace of mind, and empowering caregivers to make informed life-saving decisions.

NG-LOOP

Nasogastric (NG) tube dislodgement occurs when the feeding tube tip becomes significantly displaced from its intended position in the stomach, causing fatal consequences such as aspiration pneumonia. Compared to the 50% dislodgement rate in the general patient population, infant patients are particularly affected ( >60%) due to their miniature anatomy and tendency to unknowingly tug on uncomfortable tubes. Our solution, the Nasogastric Lightweight Observation and Oversight Product (NG-LOOP) provides comprehensive protection from NG tube dislodgement. Physical stabilization is combined with sensor feedback to detect and manage downstream complications of tube dislodgement. The lightweight external bridle, printed with biocompatible Accura 25 and coated with hydrocolloid dressing for comfort and grip, can prevent dislodgement 100% of the time given a tonic force of 200g. The sensor feedback system uses a DRV5055 linear hall effect sensor with a preset difference threshold, coupled with an SMS alert and smart plug inactivation of the feeding pump. A sensitivity of 90% and specificity of 100% in dislodgement detection was achieved under various conditions, with all feedback mechanisms being initiated in response to 100% of threshold triggers. Future steps involve integration with hospital-grade feeding pumps, improving the user interface, and incorporating more sizes for diverse age inclusivity.

Photos courtesy of Afraah Shamim, Coordinator of Educational Laboratories in the Penn BE Labs. View more photos on the Penn BE Labs Instagram.

Senior Design (BE 4950 & 4960) is a two-semester capstone course taught by David Meaney, Solomon R. Pollack Professor in Bioengineering and Senior Associate Dean of Penn Engineering, Erin Berlew, Research Scientist in the Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Lecturer in Bioengineering, and Dayo Adewole, Postdoctoral Fellow of Otorhinolaryngology (Head and Neck Surgery) in the Perelman School of Medicine. Read more stories featuring Senior Design in the BE Blog.