Every cell in your body has a copy of your genome, tightly coiled and packed into its nucleus. Since every copy is effectively identical, the difference between cell types and their biological functions comes down to which, how and when the individual genes in the genome are expressed, or translated into proteins.

Scientists are increasingly understanding the role that genome folding plays in this process. The way in which that linear sequence of genes are packed into the nucleus determines which genes come into physical contact with each other, which in turn influences gene expression.

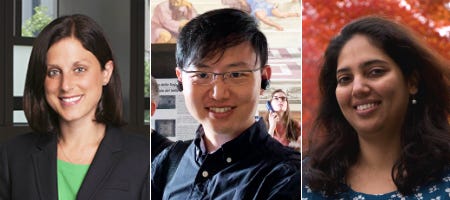

Jennifer Phillips-Cremins, assistant professor in Penn Engineering’s Department of Bioengineering, is a pioneer in this field, known as “3-D Epigenetics.” She and her colleagues have now demonstrated a new technique for quickly creating specific folding patterns on demand, using light as a trigger.

The technique, known as LADL or light-activated dynamic looping, combines aspects of two other powerful biotechnological tools: CRISPR/Cas9 and optogenetics. By using the former to target the ends of a specific genome fold, or loop, and then using the latter to snap the ends together like a magnet, the researchers can temporarily create loops between exact genomic segments in a matter of hours.

The ability to make these genome folds, and undo them, on such a short timeframe makes LADL a promising tool for studying 3D-epigenetic mechanisms in more detail. With previous research from the Phillips-Cremins lab implicating these mechanisms in a variety of neurodevelopmental diseases, they hope LADL will eventually play a role in future studies, or even treatments.

Alongside Phillips-Cremins, lab members Ji Hun Kim and Mayuri Rege led the study, and Jacqueline Valeri, Aryeh Metzger, Katelyn R. Titus, Thomas G. Gilgenast, Wanfeng Gong and Jonathan A. Beagan contributed to it. They collaborated with associate professor of Bioengineering Arjun Raj and Margaret C. Dunagin, a member of his lab.

The study was published in the journal Nature Methods.

“In recent years,” Phillips-Cremins says, “scientists in our fields have overcome technical and experimental challenges in order to create ultra-high resolution maps of how the DNA folds into intricate 3D patterns within the nucleus. Although we are now capable of visualizing the topological structures, such as loops, there is a critical gap in knowledge in how genome structure configurations contribute to genome function.”

In order to conduct experiments on these relationships, researchers studying these 3D patterns were in need of tools that could manipulate specific loops on command. Beyond the intrinsic physical challenges — putting two distant parts of the linear genome in physical contact is quite literally like threading a needle with a thread that is only a few atoms thick — such a technique would need to be rapid, reversible and work on the target regions with a minimum of disturbance to neighboring sequences.

The advent of CRISPR/Cas9 solved the targeting problem. A modification of the gene editing tool allowed researchers to home in on the desired sequences of DNA on either end of the loop they wanted to form. If those sequences could be engineered to seek one another out and snap together under the other necessary conditions, the loop could be formed on demand.

Cremins Lab members then sought out biological mechanisms that could bind the ends of the loops together, and found an ideal one in the toolkit of optogenetics. The proteins CIB1 and CRY2, found in Arabidopsis, a flowering plant that’s a common model organism for geneticists, are known to bind together when exposed to blue light.

“Once we turn the light on, these mechanisms begin working in a matter of milliseconds and make loops within four hours,” says Rege. “And when we turn the light off, the proteins disassociate, meaning that we expect the loop to fall apart.”

“There are tens of thousands of DNA loops formed in a cell,” Kim says. “Some are formed slowly, but many are fast, occurring within the span of a second. If we want to study those faster looping mechanisms, we need tools that can act on a comparable time scales.”

Fast acting folding mechanisms also have an advantage in that they lead to fewer perturbations of the surrounding genome, reducing the potential for unintended effects that would add noise to an experiment’s results.

The researchers tested LADL’s ability to create the desired loops using their high-definition 3D genome mapping techniques. With the help of Arjun Raj, an expert in measuring the activity of transcriptional RNA sequences, they also were able to demonstrate that the newly created loops were impacting gene expression.

The promise of the field of 3D-epigenetics is in investigating the relationships between these long-range loops and mechanisms that determine the timing and quantity of the proteins they code for. Being able to engineer those loops means researchers will be able to mimic those mechanisms in experimental conditions, making LADL a critical tool for studying the role of genome folding on a variety of diseases and disorders.

“It is critical to understand the genome structure-function relationship on short timescales because the spatiotemporal regulation of gene expression is essential to faithful human development and because the mis-expression of genes often goes wrong in human disease,” Phillips-Cremins says. “The engineering of genome topology with light opens up new possibilities to understanding the cause-and-effect of this relationship. Moreover we anticipate that, over the long term, the use of light will allow us to target specific human tissues and even to control looping in specific neuron subtypes in the brain.”

The research was supported by the New York Stem Cell Foundation; Alfred P. Sloan Foundation; the National Institutes of Health through its Director’s New Innovator Award from the National Institute of Mental Health, grant no. 1DP2MH11024701, and a 4D Nucleome Common Fund, grant no. 1U01HL1299980; and the National Science Foundation through a joint NSF-National Institute of General Medical Sciences grant to support research at the interface of the biological and mathematical sciences, grant no. 1562665, and a Graduate Research Fellowship, grant no. DGE-1321851.

Originally published on the Penn Engineering Medium blog.

Preeclampsia is potentially life-threatening pregnancy disorder that typically occurs in about 200,000 expectant mothers every year. With symptoms of high blood pressure, swelling of the hands and feet, and protein presence in urine, preeclampsia is usually treatable if diagnosed early enough. However, current methods for diagnosis involve invasive procedures like cordocentesis, a procedure which takes a sample of fetal blood.

Preeclampsia is potentially life-threatening pregnancy disorder that typically occurs in about 200,000 expectant mothers every year. With symptoms of high blood pressure, swelling of the hands and feet, and protein presence in urine, preeclampsia is usually treatable if diagnosed early enough. However, current methods for diagnosis involve invasive procedures like cordocentesis, a procedure which takes a sample of fetal blood. Though over ten million Americans have undergone LASIK vision corrective surgery since the option became available about 20 years ago, the procedure still poses some risk to patients. In addition to the usual risks of any surgery however, LASIK has even more due to the lack of a precise way to measure the refractive properties of the eye, which forces surgeons to make approximations in their measurements during the procedure. In an effort to eliminate this risk, a University of Maryland team of researchers in the Optics Biotech Laboratory led by

Though over ten million Americans have undergone LASIK vision corrective surgery since the option became available about 20 years ago, the procedure still poses some risk to patients. In addition to the usual risks of any surgery however, LASIK has even more due to the lack of a precise way to measure the refractive properties of the eye, which forces surgeons to make approximations in their measurements during the procedure. In an effort to eliminate this risk, a University of Maryland team of researchers in the Optics Biotech Laboratory led by

ications for this technology are enormous.

ications for this technology are enormous.