How do we know how old the universe actually is?

Balasubramanian: The universe is often reported to be 13.8 billion years old, but, truth be told, this is an amalgamation of various measurements that factor in different kinds of data involving the apparent ages of ‘stuff’ in the universe.

This stuff includes observable or ordinary matter like you, me, galaxies far and near, stars, radiation, and the planets, then dark matter—the sort of matter that doesn’t interact with light and which makes up about 27% of the universe—and finally, dark energy, which makes up a massive chunk of the universe, around 68%, and is what we believe is causing the universe to expand.

And so, we take as much information as we can about the stuff and build what we call a consensus model of the universe, essentially a line of best fit. We call the model the Lambda Cold Dark Matter (ΛCDM).

Lambda represents the cosmological constant, which is linked to dark energy, namely how it drives the expansion of the universe according to Einstein’s theory of general relativity. In this framework, how matter and energy behave in the universe determines the geometry of spacetime, which in turn influences how matter and energy move throughout the cosmos. Including this cosmological constant, Lambda, allows for an explanation of a universe that expands at an accelerating rate, which is consistent with our observations.

Now, the Cold Dark Matter part represents a hypothetical form of dark matter. ‘Dark’ here means that it neither interacts with nor emits light, so it’s very hard to detect. ‘Cold’ refers to the fact that its particles move slowly because when things cool down their components move less, whereas when they heat up the components get excited and move around more relative to the speed of light.

So, when you consider the early formation of the universe, this ‘slowness’ influences the formation of structures in the universe like galaxies and clusters of galaxies, in that smaller structures like the galaxies form before the larger ones, the clusters.

Devlin: And then taking a step back, the way cosmology works and pieces how old things are is that we look at the way the universe looks today, how all the structures are arranged within it, and we compare it to how it used to be with a set of cosmological parameters like Cosmic Microwave Background (CMB) radiation, the afterglow of the Big Bang, and the oldest known source of electromagnetic radiation, or light. We also refer to it as the baby picture of the universe because it offers us a glimpse of what it looked like at 380,000 years old, long before stars and galaxies were formed.

And what we know about the physical nature of the universe from the CMB is that it was something really smooth, dense, and hot. And as it continued to expand and cool, the density started to vary, and these variations became the seeds for the formation of cosmic structures.

The denser regions of the universe began to collapse under their own gravity, forming the first stars, galaxies, and clusters of galaxies. So, this is why, when we look at the universe today, we see this massive cosmic web of galaxies and clusters separated by vast voids. This process of structure formation is still ongoing.

And, so, the ΛCDM model suggests that the primary driver of this structure formation was dark matter, which exerts gravity and which began to clump together soon after the Big Bang. These clumps of dark matter attracted the ordinary matter, forming the seeds of galaxies and larger cosmic structures.

So, with models like the ΛCDM and the knowledge of how fast light travels, we can add bits of information, or parameters, and we have from things like the CMB and other sources of light in our universe, like the ones we get from other distant galaxies, and we see this roadmap for the universe that gives us it’s likely age. Which we think is somewhere in the ballpark of 13.8 billion years.

Read the full Q&A in Penn Today.

Vijay Balasubramanian is the Cathy and Marc Lasry Professor in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the School of Arts & Sciences at the University of Pennsylvania. He is a member of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group.

Mark Devlin is the Reese W. Flower Professor of Astronomy and Astrophysics in the Department of Physics and Astronomy in the School of Arts & Sciences at Penn.

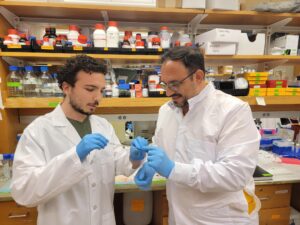

Cosette Tomita, a master’s student in Bioengineering, spoke with Penn Engineering Graduate Admissions about her research in cellular therapy and her path to Penn Engineering.

Cosette Tomita, a master’s student in Bioengineering, spoke with Penn Engineering Graduate Admissions about her research in cellular therapy and her path to Penn Engineering.

A research team led by engineers at the

A research team led by engineers at the