by Meredith Mann

A multiracial Black and Asian self-described secular humanist, who was raised as one of Jehovah’s Witnesses and is now in an interracial, interfaith marriage, walked into a Passover seder.

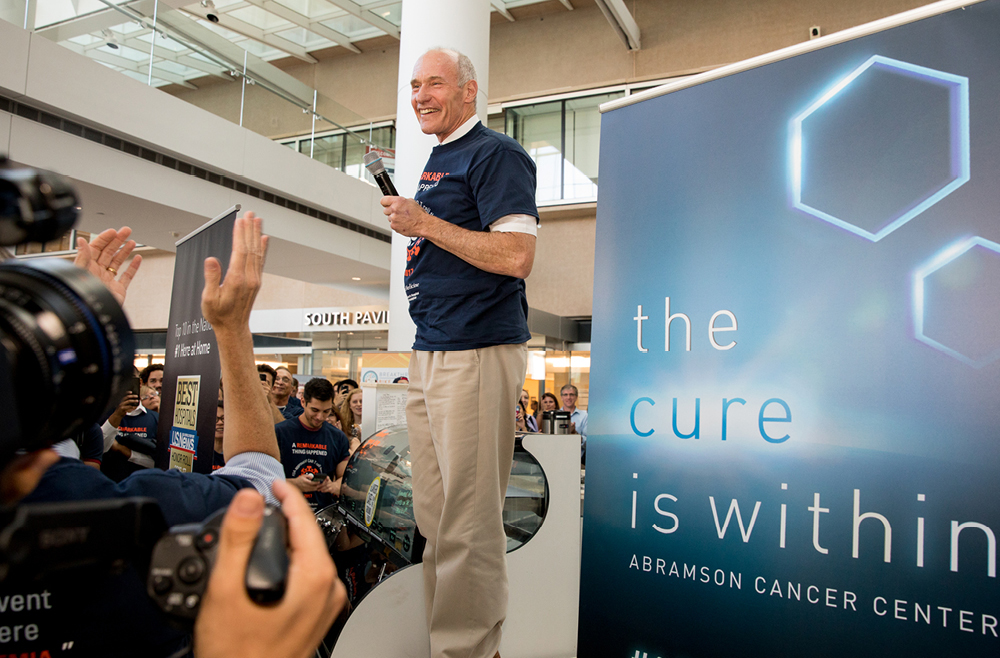

It’s not the setup for a groaner of a joke, or an epic fail of an evening. Rather, as Roy H. Hamilton, MD, tells it, this was his experience this spring as his Jewish in-laws—the family he has loved as his own for over two decades—came together to commemorate the universal human themes of freedom and deliverance from oppression reflected in the Passover narrative. Though he does this every year, this year he had some trepidation. In a time marked by tragic conflict and with tensions both abroad and at home, it seemed like having a frank discussion of these themes might invite acrimony. But what emerged instead was a profound opportunity to listen, to appreciate each other’s perspective, and to “exercise empathy for trauma that’s happening to everyone.”

It was a bit of a revelation for Hamilton, Penn Medicine’s new vice dean for Inclusion, Diversity, and Equity. “In the moment that you would have thought would be the worst to open up certain topics, we all ended up having a great dialogue across differences,” he said. Why? “Because we all felt connected enough to give each other respect, compassion, and grace, even when our thoughts and opinions differed. It made me think about how we can further cultivate a culture of empathy at Penn too.”

Today, as Hamilton begins his third decade on the faculty at Penn’s Perelman School of Medicine, he is devoted to making academia a safe, supportive space for students and colleagues alike. He serves as a professor of Neurology, with secondary appointments in Psychiatry and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. Hamilton is also director of both the Laboratory for Cognition and Neural Stimulation; and the Penn Brain Science, Translation and Modulation (BrainSTIM) Center. Previously, he was the Perelman School of Medicine’s assistant dean for Cultural Affairs and Diversity for almost a decade, and launched similar efforts in his field, serving as Penn Neurology’s vice chair for Diversity and Inclusion from 2017 until his recent elevation to the role for Penn Medicine as a whole.

Given his own diverse background and personal life, Hamilton wants everyone—trainees, faculty, patients—to feel valued and included. “I touch enough spaces in my personal life that when groups are being clearly systematically disadvantaged, it often feels like it’s touching on some piece of my own identity,” he said, in discussing his background and hope for his new leadership position. “I bring a lot of myself to this role.”

In a recent discussion, Hamilton shared perspectives on why supporting inclusion, diversity, and equity matters—particularly for an institution training future doctors—and what Penn Medicine is doing in this sphere.

Read the full interview in Penn Medicine News.

Roy H. Hamilton, M.D., M.S. is a Professor in the departments of Neurology, Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, and Psychiatry in the Perelman School of Medicine and a member of the Penn Bioengineering Graduate Group. He is Director of the Laboratory for Cognition and Neural Stimulation (LCNS).

Cosette Tomita, a master’s student in Bioengineering, spoke with Penn Engineering Graduate Admissions about her research in cellular therapy and her path to Penn Engineering.

Cosette Tomita, a master’s student in Bioengineering, spoke with Penn Engineering Graduate Admissions about her research in cellular therapy and her path to Penn Engineering.