by Sophie Burkholder

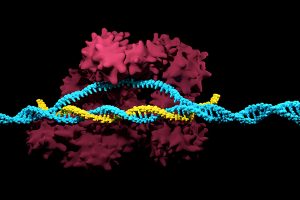

Positive results in first-in-U.S. trial of CRISPR-edited immune cells

Genetically editing a cancer patient’s immune cells using CRISPR/Cas9 technology, then infusing those cells back into the patient appears safe and feasible based on early data from the first-ever clinical trial to test the approach in humans in the United States. Researchers from the Abramson Cancer Center have infused three participants in the trial thus far—two with multiple myeloma and one with sarcoma—and have observed the edited T cells expand and bind to their tumor target with no serious side effects related to the investigational approach. Penn is conducting the ongoing study in cooperation with the Parker Institute for Cancer Immunotherapy and Tmunity Therapeutics.

“This trial is primarily concerned with three questions: Can we edit T cells in this specific way? Are the resulting T cells functional? And are these cells safe to infuse into a patient? This early data suggests that the answer to all three questions may be yes,” says the study’s principal investigator Edward A. Stadtmauer, section chief of Hematologic Malignancies at Penn. Stadtmauer will present the findings next month at the 61st American Society of Hematology Annual Meeting and Exposition.

Read the rest of the story on Penn Today.

Tulane researchers join NIH HEAL initiative for research into opioid crisis

A Tulane University professor and researcher of biomedical engineering will join fellow researchers from over 40 other institutions in the National Institute of Health’s Help to End Addiction Long-Term (HEAL) Initiative. Of the $945 million that make up the project, Michael J. Moore, Ph.D. will receive a share of $1.2 million to advance research in modeling human pain through computer chips, with the help of fellow Tulane researchers Jeffrey Tasker, Ph.D., and James Zadina, Ph.D., each with backgrounds in neuroscience.

Because of the opioid epidemic sweeping the nation, Moore notes that there’s a rapid search going on to develop non-addictive painkiller options. However, he also sees a gap in adequate models to test those new drugs before human clinical trials are allowed to take place. Here is where he hopes to step in and bring some innovation to the field, by integrating living human cells into a computer chip for modeling pain mechanisms. Through his research, Moore wants to better understand not only how some drugs can induce pain, but also how patients can grow tolerant to some drugs over time. If successful, Moore’s work will lead to a more rapid and less expensive screening option for experimental drug advancements.

New machine learning-assisted microscope yields improved diagnostics

Researchers at Duke University recently developed a microscope that uses machine learning to adapt its lighting angles, colors, and patterns for diagnostic tests as needed. Most microscopes have lighting tailored to human vision, with an equal distribution of light that’s optimized for human eyes. But by prioritizing the computer’s vision in this new microscope, researchers enable it to see aspects of samples that humans simply can’t, allowing for a more accurate and efficient diagnostic approach.

Led by Roarke W. Horstmeyer, Ph.D., the computer-assisted microscope will diffuse light through a bowl-shaped source, allowing for a much wider range of illumination angles than traditional microscopes. With the help of convolutional neural networks — a special kind of machine learning algorithm — Horstmeyer and his team were able to tailor the microscope to accurately diagnose malaria in red blood cell samples. Where human physicians typically perform similar diagnostics with a rate of 75 percent accuracy, this new microscope can do the same work with 90 percent accuracy, making the diagnostic process for many diseases much more efficient.

Case Western Reserve University researchers create first-ever holographic map of brain

A Case Western Reserve University team of researchers recently spearheaded a project in creating an interactive holographic mapping system of the human brain. The design, which is believed to be the first of its kind, involves the use of the Microsoft HoloLens mixed reality platform. Lead researcher Cameron McIntyre, Ph.D., sees this mapping system as a better way of creating holographic navigational routes for deep brain stimulation. Recent beta tests with the map by clinicians give McIntyre hope that the holographic representation will help them better understand some of the uncertainties behind targeted brain surgeries.

More than merely providing a useful tool, McIntyre’s project also brings together decades’ worth of neurological data that has not yet been seriously studied together in one system. The three-dimensional atlas, called “HoloDBS” by his lab, provides a way of finally seeing the way all of existing neuro-anatomical data relates to each other, allowing clinicians who use the tool to better understand the brain on both an analytical and visual basis.

Implantable cancer traps reduce biopsy incidence and improve diagnostic

Biopsies are one of the most common procedures used for cancer diagnostics, involving a painful and invasive surgery. Researchers at the University of Michigan are trying to change that. Lonnie Shea, Ph.D., a professor of biomedical engineering at the university, worked with his lab to develop implants with the ability to attract any cancer cells within the body. The implant can be inserted through a scaffold placed under the patient’s skin, making it a more ideal option than biopsy for inaccessible organs like lungs.

The lab’s latest work on the project, published in Cancer Research, details its ability to capture metastatic breast cancer cells in vivo. Instead of needing to take biopsies from areas deeper within the body, the implant allows for a much simpler surgical procedure, as biopsies can be taken from the implant itself. Beyond its initial diagnostic advantages, the implant also has the ability to attract immune cells with tumor cells. By studying both types of cells, the implant can give information about the current state of cancer in a patient’s body and about how it might progress. Finally, by attracting tumor and immune cells, the implant has the ability to draw them away from the area of concern, acting in some ways as a treatment for cancer itself.

People and Places

The Philadelphia Inquirer recently published an article detailing the research of Penn’s Presidential Assistant Professor in Psychiatry, Microbiology, and Bioengineering, Cesar de la Fuente, Ph.D. In response to a growing level of worldwide deaths due to antibiotic-resistant bacteria, de la Fuente and his lab use synthetic biology, computation, and artificial intelligence to test hundreds of millions of variations in bacteria-killing proteins in the same experiment. Through his research, de la Fuente opens the door to new ways of finding and testing future antibiotics that might be the only viable options in a world with an increasing level of drug-resistant bacteria

Emily Eastburn, a Ph.D. candidate in Bioengineering at Penn and a member of the Boerckel lab of the McKay Orthopaedic Research Laboratory, recently won the Ashton fellowship. The Ashton fellowship is an award for postdoctoral students in any field of engineering that are under the age of 25, third-generation American citizens, and residents of either Pennsylvania or New Jersey. A new member of the Boerckel lab, having joined earlier this fall, Eastburn will have the opportunity to conduct research throughout her Ph.D. program in the developmental mechanobiology and regeneration that the Boerckel lab focuses on.