By Lauren Salig

SpaceX launched its 17th resupply mission to the International Space Station on May 4, with bioengineering professor Dan Huh’s organ-on-a-chip experiments in tow.

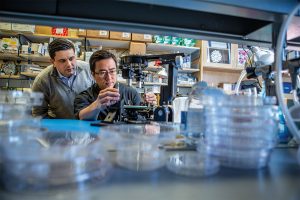

Dan Huh, the Wilf Family Term Assistant Professor in the Department of Bioengineering, researches human organs and the diseases that infect them by engineering devices made of living cells that act as stand-ins for organs. Huh’s lab has developed imitations of many organs, including the placenta and the eye, but it’s his lung-on-a-chip and his bone-marrow-on-a-chip that are reaching unprecedented heights as part of a new experiment taking place at the International Space Station (ISS).

On May 4, SpaceX launched a ISS-bound cargo capsule carrying Huh’s organ-on-a-chip experiments, which will remain in space for a month. Once back on Earth, the chips that spent time in space will be compared to control chips from Huh’s lab that are being monitored in parallel. Huh’s team is looking to see how being in space affects bacterial infections in lungs and white blood cell behavior in bone marrow. The researchers’ hope is that their studies will reveal important information about how human organs function both in space and on Earth.

Daniel Oberhaus of WIRED wrote an article describing the multiple organs-on-a-chip experiments being conducted at the ISS, including the two experiments headed by Huh:

Dan Huh is a bioengineer at the University of Pennsylvania and the lead researcher on the lung tissue chip headed to the ISS. This lung chip models a human airway and will be infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa, a species of bacteria that had previously been found on the ISS. On Earth this bacteria is usually associated with respiratory infections, which are one of the leading types of illness on long-duration missions to the ISS.

Huh says scientists still know very little about why astronauts’ immune response seems to become suppressed in orbit, and the tissue chips are aimed at building a better understanding of the phenomenon.

Originally posted at the Penn Engineering Medium Blog.

Read the entire article at WIRED.