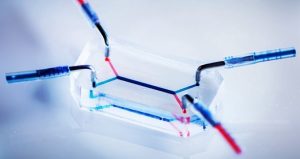

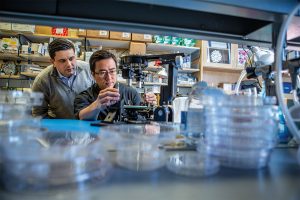

Dan Huh, Associate Professor in the Department of Bioengineering, has been steadily growing a collection of organs-on-chips. These devices incorporate human cells into precisely engineered microfluidic channels that mimic an organ’s natural environment, providing a way to conduct experiments that would not otherwise be feasible.

Huh’s previous research has involved using a placenta-on-a-chip to study which drugs are able to reach a developing fetus; investigating microgravity’s effect on the immune system by sending one of his chips to the International Space Station; and testing treatments for dry eye disease using an eye-on-a-chip, complete with a mechanical blinking eyelid.

Now, he and his colleagues are taking this technology out of their lab and into industry with their company, Vivodyne.

Andrei Georgescu, Huh’s lab-member and co-founder of Vivodyne, recently spoke with Technical.ly Philly’s Paige Gross about the growth of their company.

Research into potential drugs is usually performed first on mice, and success is only found in a fraction of humans once implemented in clinical trials, Andrei Georgescu, cofounder and CEO of Vivodyne, told Technical.ly. The genetic makeup just isn’t similar enough. But technology that allows scientists to test therapies on lab-grown human organs called “organs on chip” is allowing for testing without human subjects.

The organs on chip allow for a drug to react to tissue in a more similar way to the body than it would in a petri dish, Georgescu said. Cells sense their environment very well, he added.

“We’re making the environment more complicated, making its spacial features complicated enough to match the native complexity of the organs,” he said. “When [cells] sense a softer environment, they start to behave more realistically. Their response to the drug is more realistic.”

Continue reading “This Penn-founded biotech company specializing in human ‘organs on chip’ raised $4M” at Technical.ly Philly.

Originally posted in Penn Engineering Today.