by Andrew E. Mathis

In January 1951, Henrietta Lacks, a 30-year-old African-American woman from Baltimore, was diagnosed with cervical cancer at the Johns Hopkins Medical Center. She was treated with radium brachytherapy, the standard of care at the time, but her condition worsened. In August, a week after she turned 31, she was admitted to the hospital with severe abdominal pain. Less than three months later, she died. An autopsy showed widespread metastasis of the original cancer.

Henrietta Lacks had died, but strangely, her cancer cells have lived on. Unbeknownst to her and her family, Henrietta’s doctors had sampled her cancer cells for research — a common practice at the time, particularly from patients treated in wards. Those cells were given to George Gey, a JHU biologist who had been trying for years to establish a cancer cell line that could be grown outside the body. Henrietta Lacks’s cells ended up being the first cell line so established.

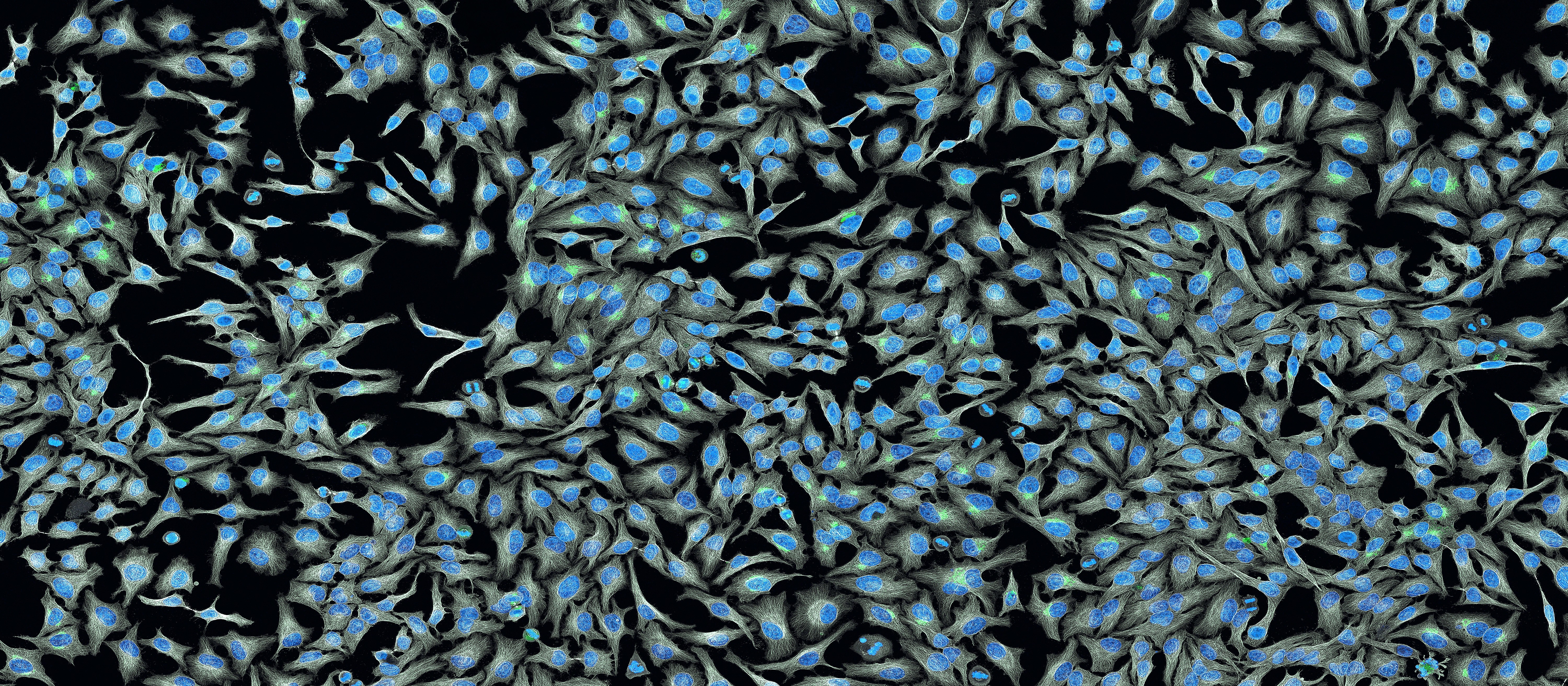

The cell line was named “HeLa” by Gey’s laboratory assistant, who coded cell samples using the first two letters of the donor’s first and last names. With Henrietta Lacks’s cells, Gey was able to establish an immortal cell line, i.e., a line of cells that would continue to divide indefinitely. The ability of these cells to divide like this lent itself to the line being used in numerous scientific studies since the 1950s, including Jonas Salk’s development of the polio vaccine.

Notwithstanding the tremendous accomplishments achieved using the HeLa cell line, the case nevertheless evokes serious ethical issues regarding the consent of patients to having their tissue used for research. In recent years, the case has attracted significant attention, with a book, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks, published by Rebecca Skloot in 2010 and now an HBO feature film of the same title produced by and starring Oprah Winfrey as Lacks’s daughter. The film debuted on April 22.

Brittany Shields, PhD, a senior lecturer in the Department of Bioengineering at the University of Pennsylvania, discussed some of the issue raised by Lacks’s story. “Henrietta Lacks’s story has brought public attention to a number of ethical issues in biomedical research, including the role of informed consent, privacy, and commercialization in the collection, use and dissemination of biospecimens,” Dr. Shields says.

“In the United States, biomedical research at federally-funded institutions must follow the policy set by the Department of Health and Human Services. The current policy, known as the ‘Common Rule,’ calls for informed consent and oversight through Institutional Review Boards for research conducted with human beings,” she explains.

However, she continues, “these regulations may or may not apply in different situations related to biospecimens. If an anonymous biospecimen had already been collected for another purpose, informed consent is generally not required.”

In the case of Henrietta Lacks, or more precisely her descendants, an agreement was reached between the family and the National Institute of Health stipulating that the family must give consent when certain genetic information gleaned from the cell line is used. However, controversy between the family and the medical research community has persisted.