by Janelle Weaver

Autoimmune disorders are among the most prevalent chronic diseases across the globe, affecting approximately 5-7% of the world’s population. Emerging treatments for autoimmune disorders focus on “adoptive cell therapies,” or those using cells from a patient’s own body to achieve immunosuppression. These therapeutic cells are recognized by the patient’s body as ‘self,’ therefore limiting side effects, and are specifically engineered to localize the intended therapeutic effect.

In treating autoimmune diseases, current adoptive cell therapies have largely centered around the regulatory T cell (Treg), which is defined by the expression of the Forkhead box protein 3, orFoxp3. Although Tregs offer great potential, using them for therapeutic purposes remains a major challenge. In particular, current delivery methods result in inefficient engineering of T cells.

Tregs only compose approximately 5-10% of circulating peripheral blood mononuclear cells. Furthermore, Tregs lack more specific surface markers that differentiate them from other T cell populations. These hurdles make it difficult to harvest, purify and grow Tregs to therapeutically relevant numbers. Although there are additional tissue-resident Tregs in non-lymphoid organs such as in skeletal muscle and visceral adipose tissue, these Tregs are severely inaccessible and low in number.

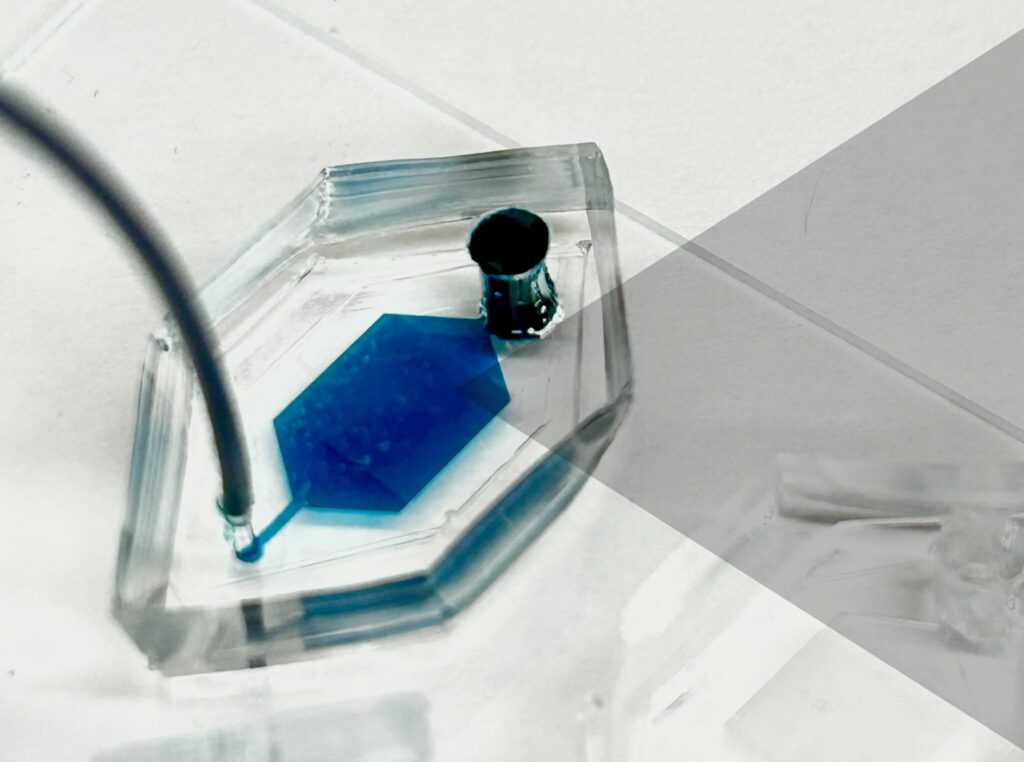

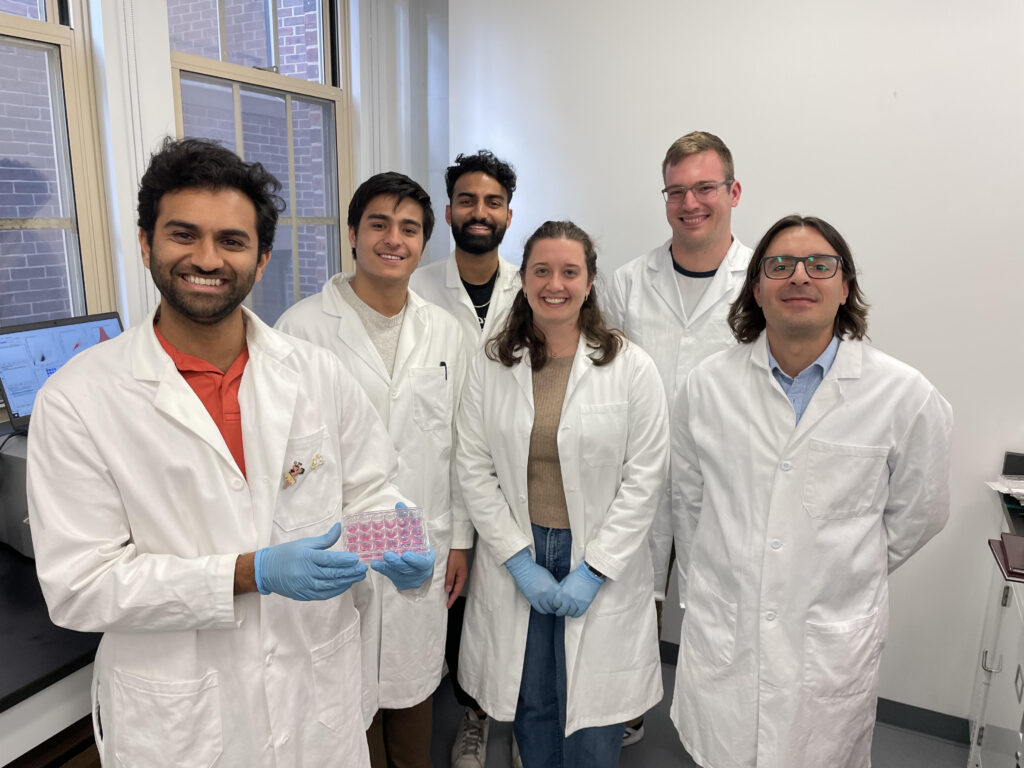

Now, a research team led by Michael Mitchell, Associate Professor in Bioengineering in the School of Engineering and Applied Science at the University of Pennsylvania, has developed a lipid nanoparticle (LNP) platform to deliver Foxp3 messenger RNA (mRNA) to T cells for applications in autoimmunity. Their findings are published in the journal Nano Letters.

“The major challenges associated with ex vivo (outside the body) cell engineering are efficiency, toxicity, and scale-up: our mRNA lipid nanoparticles (mRNA LNPs) allow us to overcome all of these issues,” says Mitchell. “Our work’s novelty comes from three major components: first, the use of mRNA, which allows for the generation of transient immunosuppressive cells; second, the use of LNPs, which allow for effective delivery of mRNA and efficient cell engineering; and last, the ex vivo engineering of primary human T cells for autoimmune diseases, offering the most direct pipeline for clinical translation of this therapy from bench to bedside.”

“To our knowledge, this is one of the first mRNA LNP platforms that has been used to engineer T cells for autoimmune therapies,” he continues. “Broadly, this platform can be used to engineer adoptive cell therapies for specific autoimmune diseases and can potentially be used to create therapeutic avenues for allergies, organ transplantation and beyond.”

Delivering the Foxp3 protein to T cells has been difficult because proteins do not readily cross the cell membrane. “The mRNA encodes for Foxp3 protein, which is a transcription factor that makes the T cells immunosuppressive rather than active,” explains first author Ajay Thatte, a doctoral student in Bioengineering and NSF Fellow in the Mitchell Lab. “These engineered T cells can suppress effector T cell function, which is important as T cell hyperactivity is a common phenotype in autoimmune diseases.”

Read the full story in Penn Engineering Today.