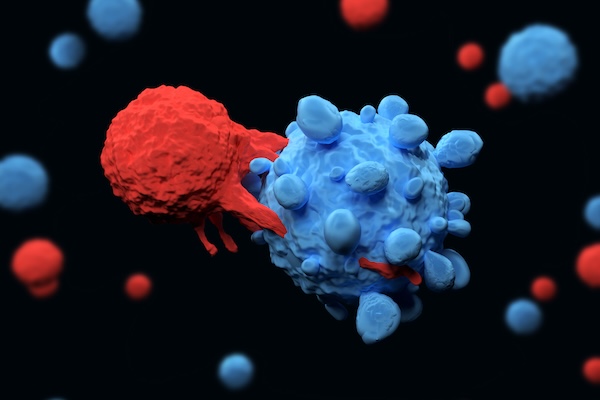

For patients with certain types of cancer, CAR T cell therapy has been nothing short of life changing. Developed in part by Carl June, Richard W. Vague Professor at Penn Medicine, and approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2017, CAR T cell therapy mobilizes patients’ own immune systems to fight lymphoma and leukemia, among other cancers.

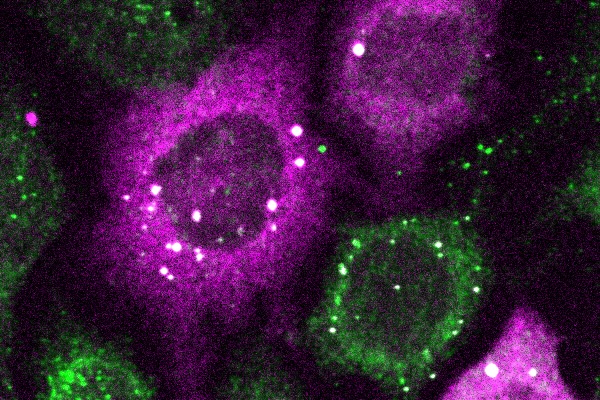

However, the process for manufacturing CAR T cells themselves is time-consuming and costly, requiring multiple steps across days. The state of the art involves extracting patients’ T cells, then activating them with tiny magnetic beads, before giving the T cells genetic instructions to make chimeric antigen receptors (CARs), the specialized receptors that help T cells eliminate cancer cells.

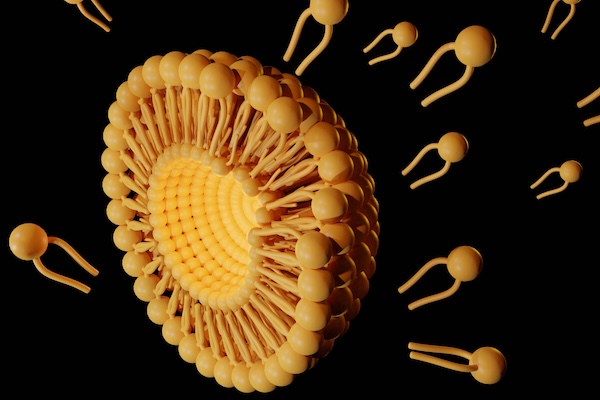

Now, Penn Engineers have developed a novel method for manufacturing CAR T cells, one that takes just 24 hours and requires only one step, thanks to the use of lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), the potent delivery vehicles that played a critical role in the Moderna and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 vaccines.

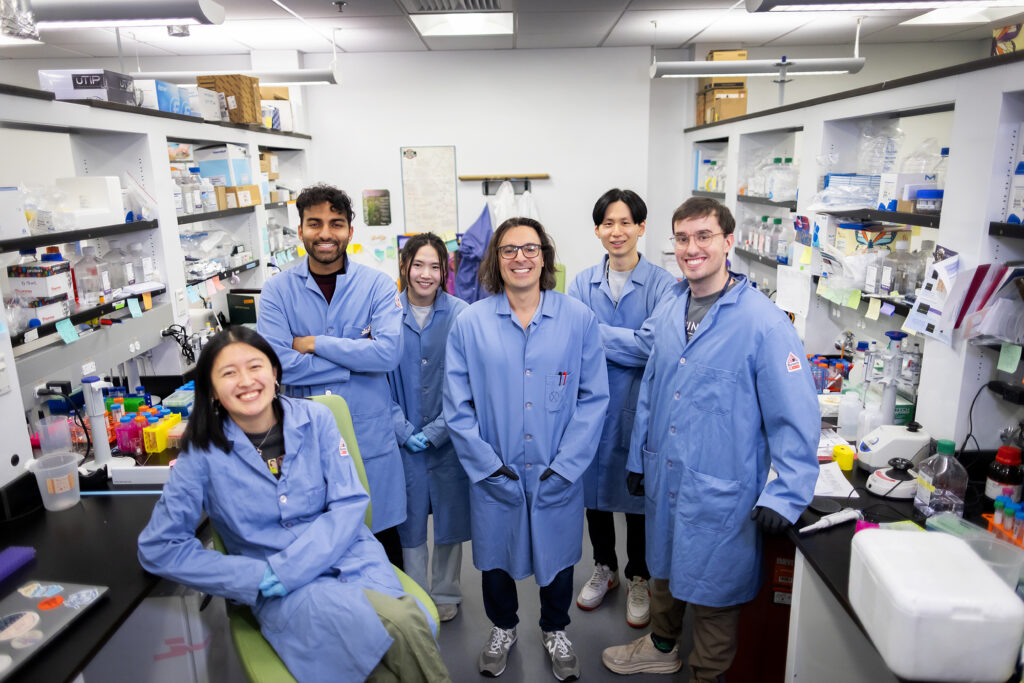

In a new paper in Advanced Materials, Michael J. Mitchell, Associate Professor in Bioengineering, describes the creation of “activating lipid nanoparticles” (aLNPs), which can activate T cells and deliver the genetic instructions for CARs in a single step, greatly simplifying the CAR T cell manufacturing process. “We wanted to combine these two extremely promising areas of research,” says Ann Metzloff, a doctoral student in Bioengineering and NSF Graduate Research Fellow in the Mitchell lab and the paper’s lead author. “How could we apply lipid nanoparticles to CAR T cell therapy?”

Read the full story in Penn Engineering Today.