By GABE Outreach Chairs and Ph.D. students David Gonzalez-Martinez and David Mai

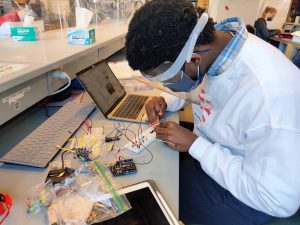

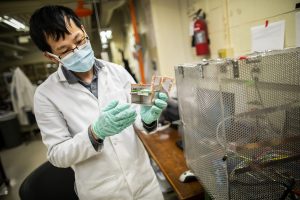

Every spring, the Graduate Association of Bioengineers (GABE) at Penn partners up with iPraxis, an educational non-profit organization based in Philadelphia, to organize BETA Day, an event that brings together Bioengineering graduate students and local Philadelphia grade school students to introduce them to the field of bioengineering, the life of graduate students, and hands-on scientific demonstrations. Due to COVID-19 restrictions, we adapted the traditional in-person BETA Day into a virtual event on Zoom. This year, we assembled kits containing the necessary materials for our chosen demonstrations and worked with iPraxis to coordinate their delivery to partner schools and their students. This enabled students to perform their demonstrations in a hands-on manner from their own homes; over 40 students were able to participate in extracting their own DNA and making biomaterials with safe household materials.

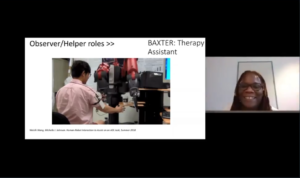

The day began with a fantastic lecture by Michelle Johnson, Associate Professor in Bioengineering and Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation, who introduced students to the field of rehabilitation robotics and shared her experience as a scientist. Students then learned about DNA and biomaterials through lectures mediated by the graduate students Dayo Adetu and Puneeth Guruprasad. After each lecture, students broke into breakout rooms with graduate student facilitators where they were able to get some hands-on scientific experience as they extracted DNA from their cheek cells and fabricated alginate hydrogels. Michael Sobrepera, a graduate student in Dr. Johnson’s lab, concluded the event by giving a lecture on the process of robotics development and discussed where the field is heading and some important considerations for the field.

While yet another online event may seem unexciting, throughout the lectures students remained exceptionally engaged and raised fantastic questions ranging from the accessibility of low income communities to novel robotic therapeutic technologies to the bioethical questions robotic engineers will face as technologies advance. The impact of BETA day was evident as the high school students began to discuss the possible majors they would like to pursue for their bachelor’s degrees. Events like BETA Day give a glimpse into possible STEM fields and careers students can pursue.